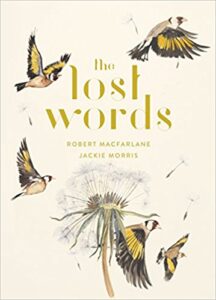

The Lost Words, written by Robert Macfarlane and illustrated by me was published in October of last year by Hamish Hamilton. The reception the book received took all involved in the making of this book by surprise I think, and over the last few months we have learned so much, from its readers and booksellers.

The work is a praise-song, in word and in image, to the natural world. Both Robert and myself have a deep love for the non-human world. I’ve loved the wild ever since I became aware of myself, although I was never allowed as a child to explore it as much as I would have liked. And yet my father taught me the names of things, and how to look, seek, find, be patient and watchful and still. As an adult I have ventured further into wild places, and haunted those times of day when many humans are asleep, as the light comes into the day, fades out of it, when the wild things take ownership of land and sky. And if my clothes are seldom free of holes it is because of my inclination to go through bushes and fences rather than around them, looking for birds, badgers, weasels and foxes. And if I am late for things it is because I am often distracted from my course by the little people of the air. I’ve always loved the shape of birds.

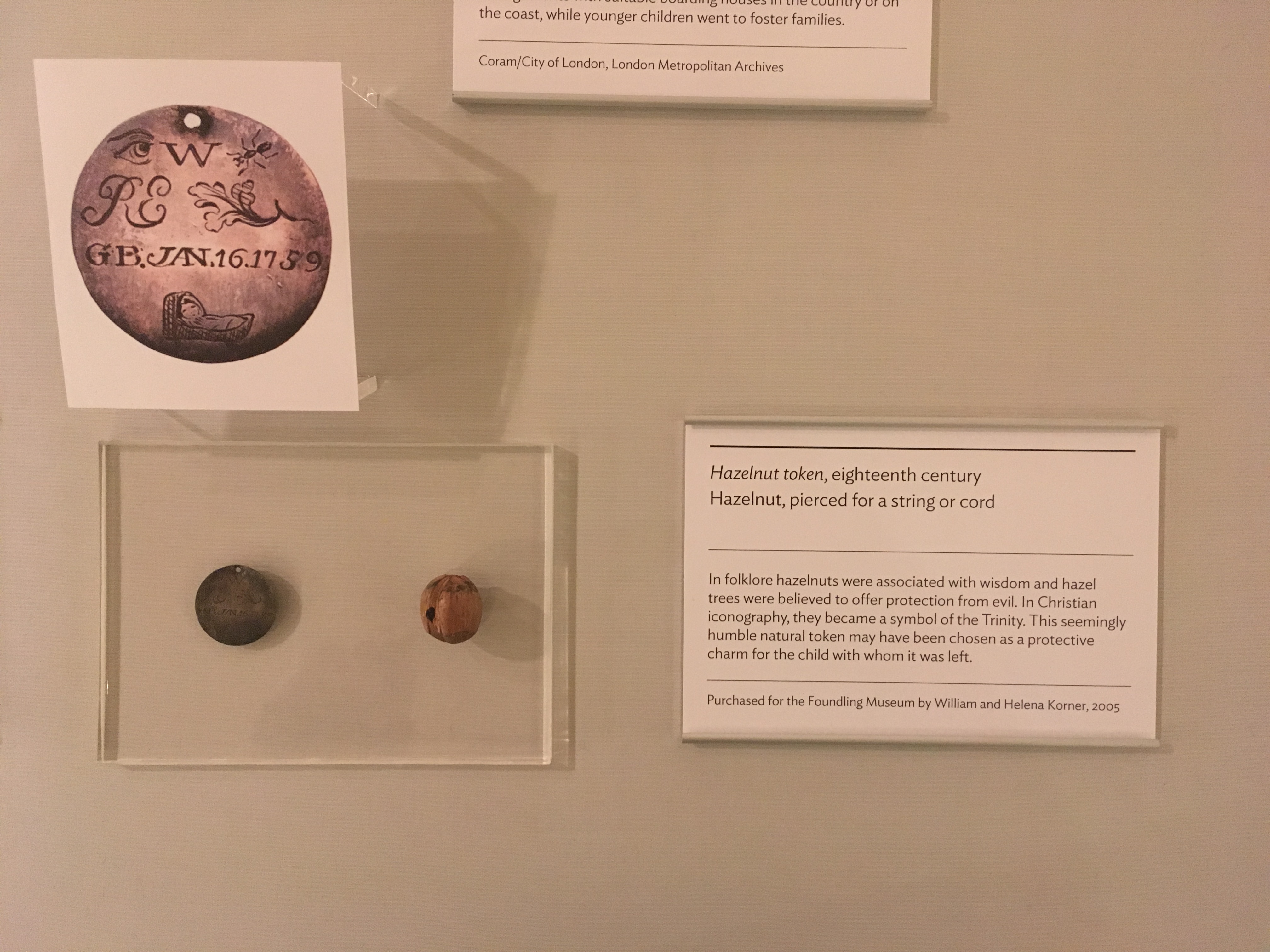

The Lost Words is not only a book. As a result of a partnership with Compton Verney, through the curatorship of Antonia Harrison, it is also a touring exhibition of word and image. The next venue for the exhibition is The Foundling Museum in London, such a beautiful place, with a bitter-sweet history. The Foundling Museum has always been supported by the work of artists. As its name suggests it was a place where abandoned children were taken, or where parents who had no means to support their children would take them, leaving them on the steps of the building. Often the child would be left with a token, a button, a thimble, a coin. Many of these tokens remain in the collection of the museum. The curator told me that “in some cases the parents were so poor all they had to leave the child was a necklace made of a piece of string with a hazelnut on”. For a while this worried away at the back of my mind. A hazelnut? Why, if you were so poor would you choose a hazelnut?

The Lost Words is about language, the naming of things, the wild words. As we have become urbanised (and this has happened in a relatively few generations. My father grew up in The Black Country, but they still kept chickens, pigs, knew the names and shapes of edible plants, took meat from the wild in the form of rabbits), the language of nature has slipped away from our minds and tongues. Children are more able to name Pokemon characters than they are to recognize British wildlife. Adults struggle to identify bird species. And I began to wonder about folklore. Has the knowledge of folklore slipped in the same direction?

Three or four generations ago children would be given time out from school to go nutting. The gathering of nuts from the hedgerows was important to the survival of many. Hazelnuts, fresh from the tree cased in green sheathes, with the brown nuts hiding that sweet and milky nutmeat was a vital protein for many through the winter months.

Hazel trees were sacred trees, beloved of druids. Hazel wands are still used in water-divining. A sacred grove of nine hazel trees grew around a clear water pool where salmon fed on the falling nuts. Wise fish, salmon, also scared to the druids. Nutshells were thought to hold wisdom, hence the phrase, ‘in a nutshell’. Hazelnuts were given to brides on their wedding days as symbols of fertility, and a double nut was a sign of twins to be born.

And in Scotland a hazelnut was worn as a talisman to protect against evil. So perhaps the hazelnut, left with the child in the care of the orphanage, was more a talisman than a gift from a mother so poor that all she had to give her child was a nut. It was a gift of protection, and love, of the old lore.

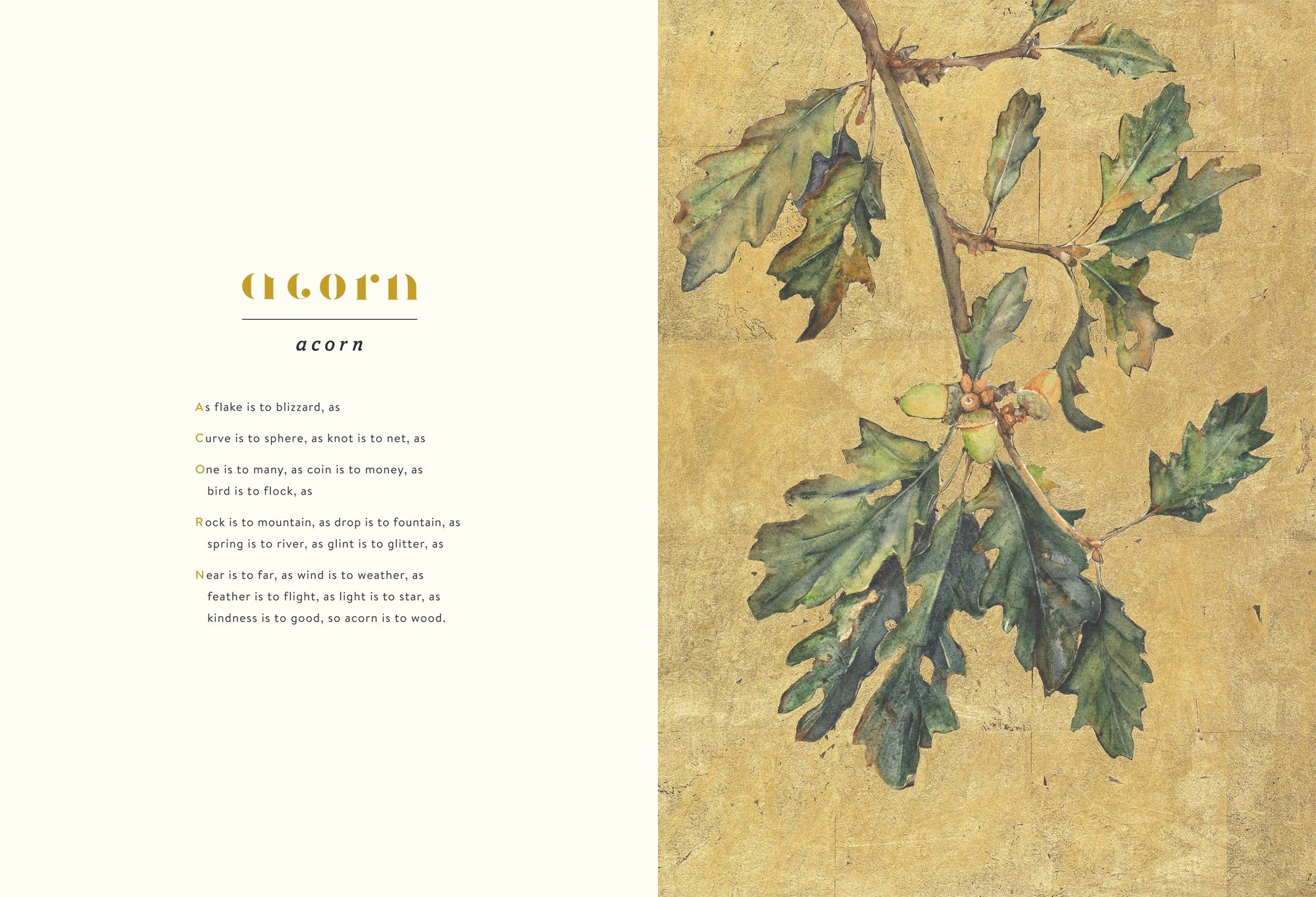

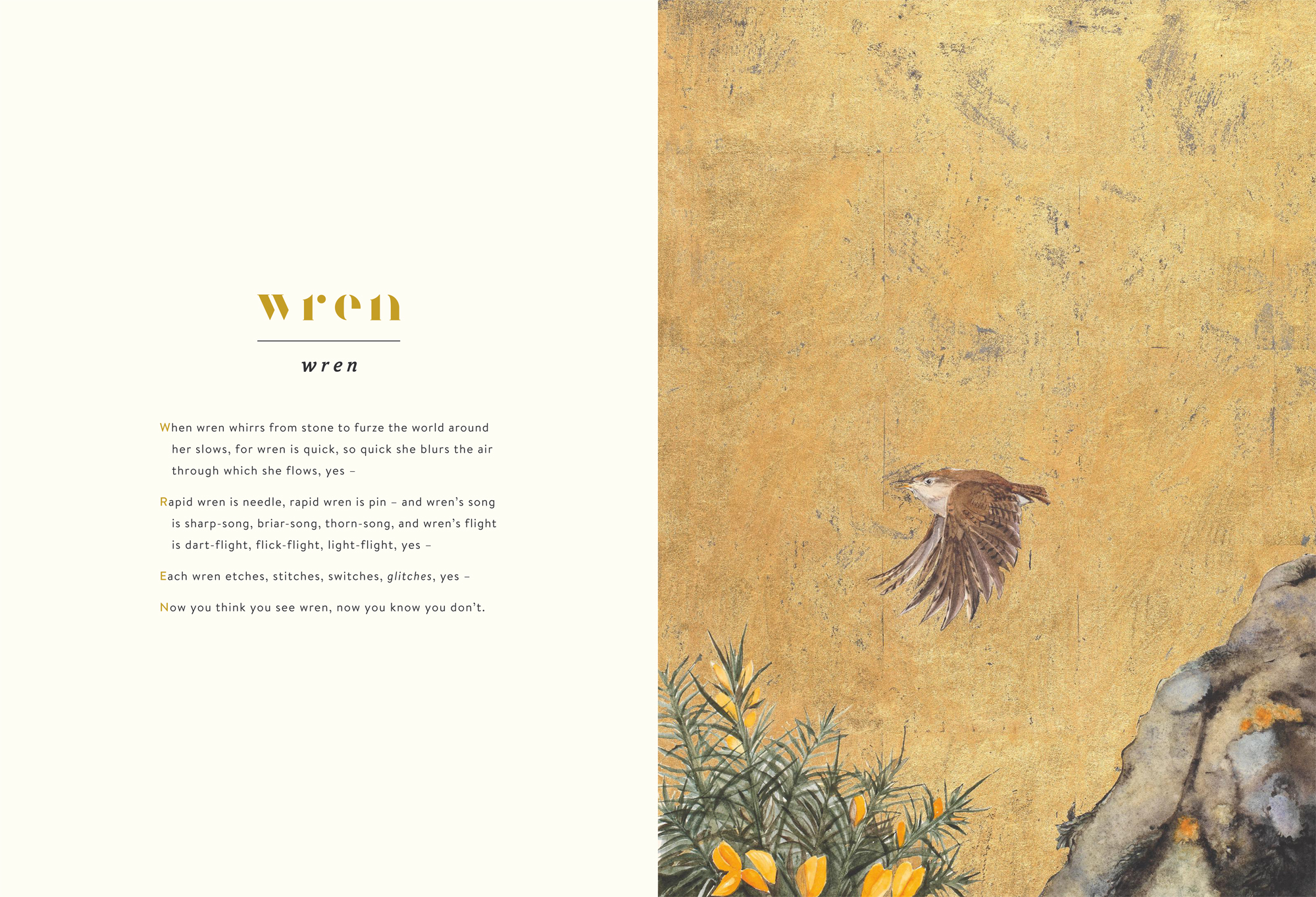

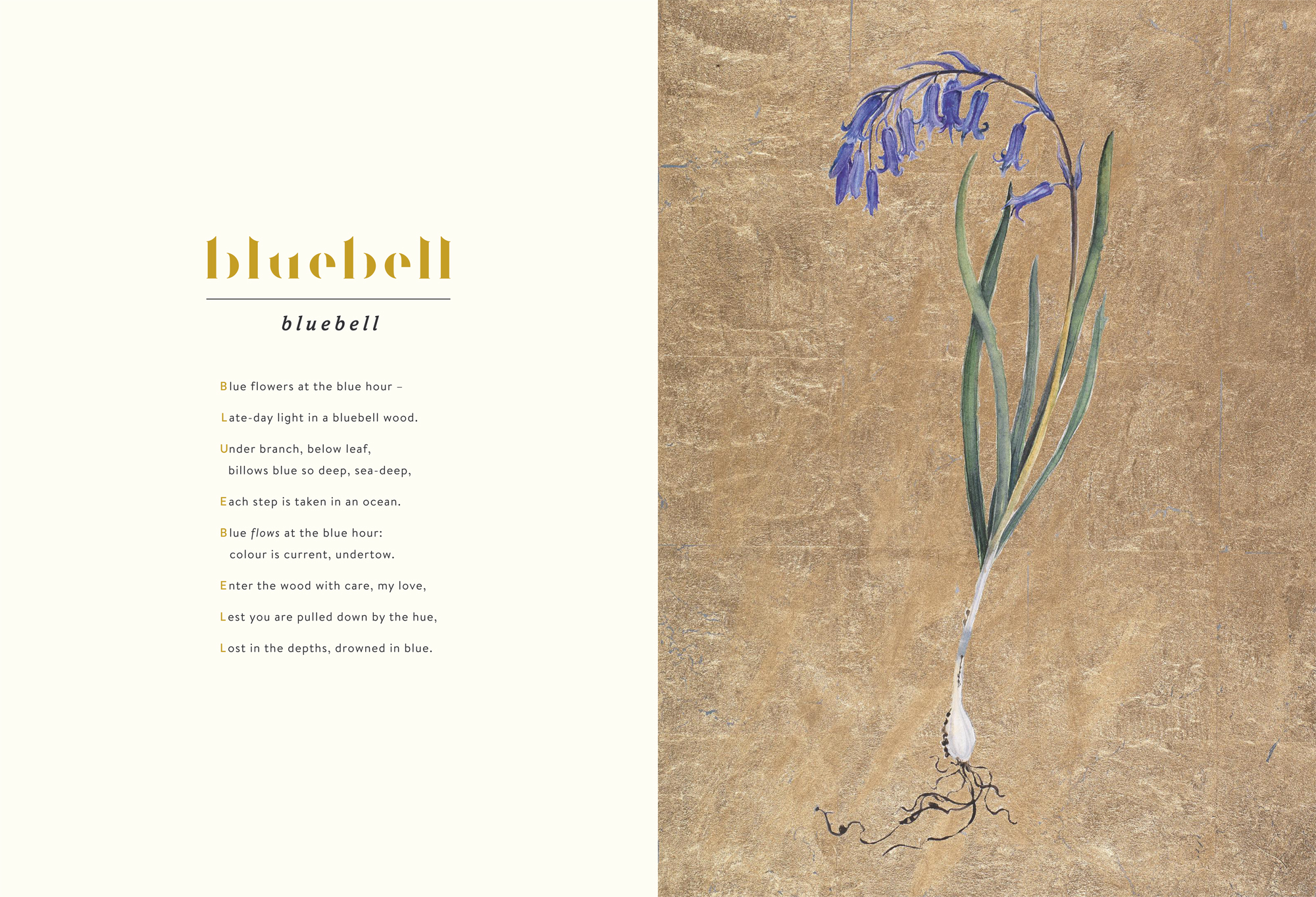

So much folklore is connected to the land, to the wild, wild things and as such is connected to the words in The Lost Words. The twitter feed of #FolkloreThursday has always been a dangerous place for me to visit. It’s such a treasury of information about the old ways, not just of the people of Britain, but of the world. From acorn to wren, The Lost Words moves through our alphabet. The acorn was a symbol of long life, of strength, and an acorn would often be carried for luck. Wrens were hunted on St Stephens Day by the wren boys. Stories twine and spin around The Lost Words. The one with the most folkloric references for me is the bluebell spell. A lyrical drowning in the senses, Robert’s spell came to me just as I had finished reading Ellen Kushner’s Thomas the Rhymer, a lyrically exquisite reworking of the folk myth of True Thomas, who dwelled in the realm of the faye folk and was ‘gifted’ with the tongue that could not lie. It seemed to me that Macfarlane was channelling his inner Thomas the Rhymer in the bluebell spell especially, singing of the wild, from the heart.

There are many links between The Lost Words and The Foundling Museum. The hazelnut is one. Before it was a museum, those whose care the children were placed in knew the value of time spent out of doors for the mental and physical health of their charges. A recent survey showed that prisoners in Britain spend more time out of doors than children in Britain do. Our book, and the exhibition, are both aimed at a re-focusing, a movement towards re-wilding, not just children, but adults also. Robert has written spells, words that almost demand to be read out loud, shared, and in the ways of magic and by ‘slight-of-word’ rather than ‘slight-of-hand’, we are trying to divert the eye, away from the human, the urban, and into the nearby wild. For we live surrounded by the wild, even in cities. Peregrines nest in most British cities now, wrens can be found almost everywhere. But if we don’t know their names, we don’t see these small brown birds, we don’t hear that sharp, thorn song.

Goldfinches, the golden icon of our book, are on the rise, partly because people see them, recognize their beautiful shape, colour, hang out bird feeders for them. The collective noun for a group of goldfinches is a charm, which chimes with our spells. And the goldfinch in folklore is a symbol of resurrection. Nature and folklore are hand in hand. To name our creatures, trees, birds, to know our stories, is to understand our place in the wild wide world.

The exhibition at The Foundling Museum runs from 19th January – 6 May 2018, after which it will travel to the Royal Botanic Gardens of Edinburgh, Inverleith House.

Win a copy of The Lost Words this month with #FolkloreThursday!

The wonderful folks over at Hamish Hamilton have offered a copy of The Lost Words, written by Robert Macfarlane and illustrated by Jackie Morris, for a lucky #FolkloreThursday newsletter subscriber this March.

‘All over the country, there are words disappearing from children’s lives. These are the words of the natural world – Dandelion, Otter, Bramble and Acorn, all gone. The rich landscape of wild imagination and wild play is rapidly fading from our children’s minds. The Lost Words stands against the disappearance of wild childhood. It is a joyful celebration of nature words and the natural world they invoke. With acrostic spell-poems by award-winning writer Robert Macfarlane and hand-painted illustration by Jackie Morris, this enchanting book captures the irreplaceable magic of language and nature for all ages.’

To be in with a chance of winning the book, put together your own story from folklore — or an acrostic spell-poem or piece of artwork — based on one of the nature words used in the book. A winner will be chosen from the entries. For a list of words, artwork and questions to help with this do take a look at the teacher’s notes from the John Muir Trust, and also Robert’s Guardian article about naming and knowing. You have until March 31st to put this together, and send it to us here at #FolkloreThursday.

Post your creative response underneath the article here, and email it to us through the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid March 2018; UK & ROI only).