An evil magic ring, associated with dwarf and dragon – what a great idea Tolkien had for his books! But he actually borrowed it from ancient Viking legends…

Tolkien’s Inspiration

Professor J. R. R. Tolkien was a renowned Oxford scholar, an expert in the ancient texts of Northern Europe. So it’s not surprising that, when he wrote The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, he drew heavily on some of the most popular legends of the Viking Age. These centred on the curse of a dwarf-forged ring, with an ongoing plot rich in lust, treachery and enchantment.

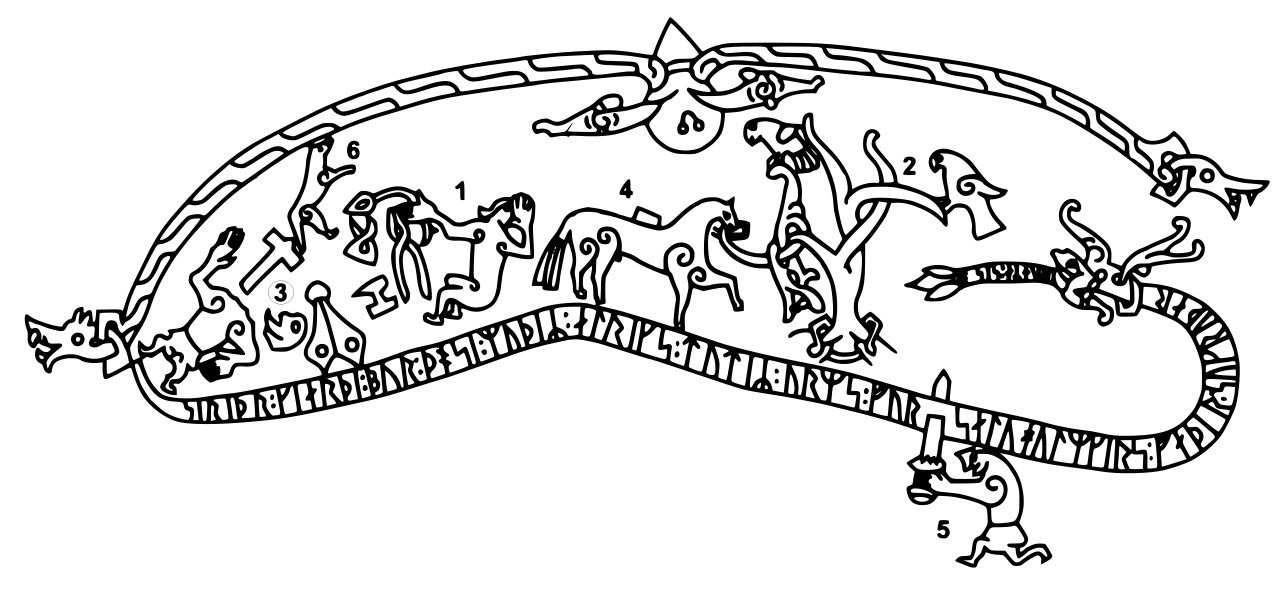

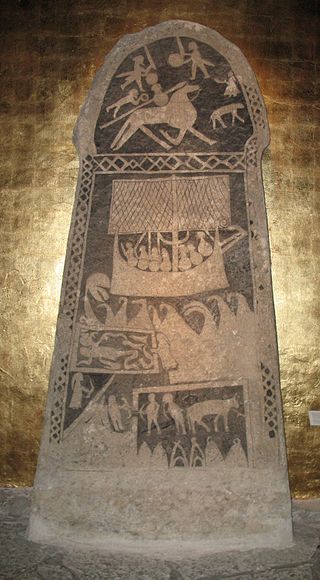

We know that these legends were really popular over a thousand years ago, because scenes from them were illustrated in many Viking Age carvings. Some of these can still be seen in England, the Isle of Man, Sweden and Norway. The complete story has also survived in several medieval Old Norse texts, which many scholars believe are transcriptions of oral storytelling traditions that also date back to the Viking Age. One of these forms part of the 13th Century Prose Edda. Its author, the great Icelandic scholar Snorri Sturluson, wrote that ‘Most poets have composed poetry based on these stories’. Fifteen examples of these can be read in the mysterious Poetic Edda; these too are believed to have a much older oral provenance and are apparently aimed at audiences who already knew the legends well. During the same period, they were even turned into a full-length novel, called Volsunga Saga.

The Origin of the Ring

Snorri describes the origin of the ring in an episode that features Odin – the high god of creation, wisdom, war and death – and the charismatic but deceitful trickster Loki:

‘Odin immediately sent Loki into the Land of the Dark Elves. There he found the dwarf Andvari, who had taken the shape of a fish in the water. Loki caught him in his hands and threatened to kill him unless he paid a ransom of all the gold that he kept in his cave. So they went to the dwarf’s cave and Andvari brought out all the gold he had, and it was great riches. The dwarf tried to conceal one small gold ring under his hand – but Loki saw it and ordered him to hand it over. The dwarf begged him not to take this ring, saying that if he kept it, this ring would produce new wealth for himself. Loki answered that the dwarf should not keep anything, and he seized the ring from him. However, as he went out, the dwarf cursed the ring to bring death and ruin to everyone who ever possessed it.’

(The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson, translated by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur, 1916)

The Evil Curse

Odin and Loki use the ring and its associated treasure hoard to pay ‘blood money’ to an unsavoury man called Hreidmar, because they had inadvertently killed one of his sons. As soon as it comes into Hreidmar’s possession, the ring begins to work its evil. Within a short time, he is slaughtered by another of his sons, Fafnir – who then seizes the ring and the treasure for himself and transforms into a dragon in order to guard it. Later, his other brother, Regin, hires the noble warrior Sigurd to kill the dragon and thus obtain the ring for him, promising to pay him well. However, once he has slain the dragon, Sigurd kills Regin too, then rides off wearing the cursed ring on his own finger.

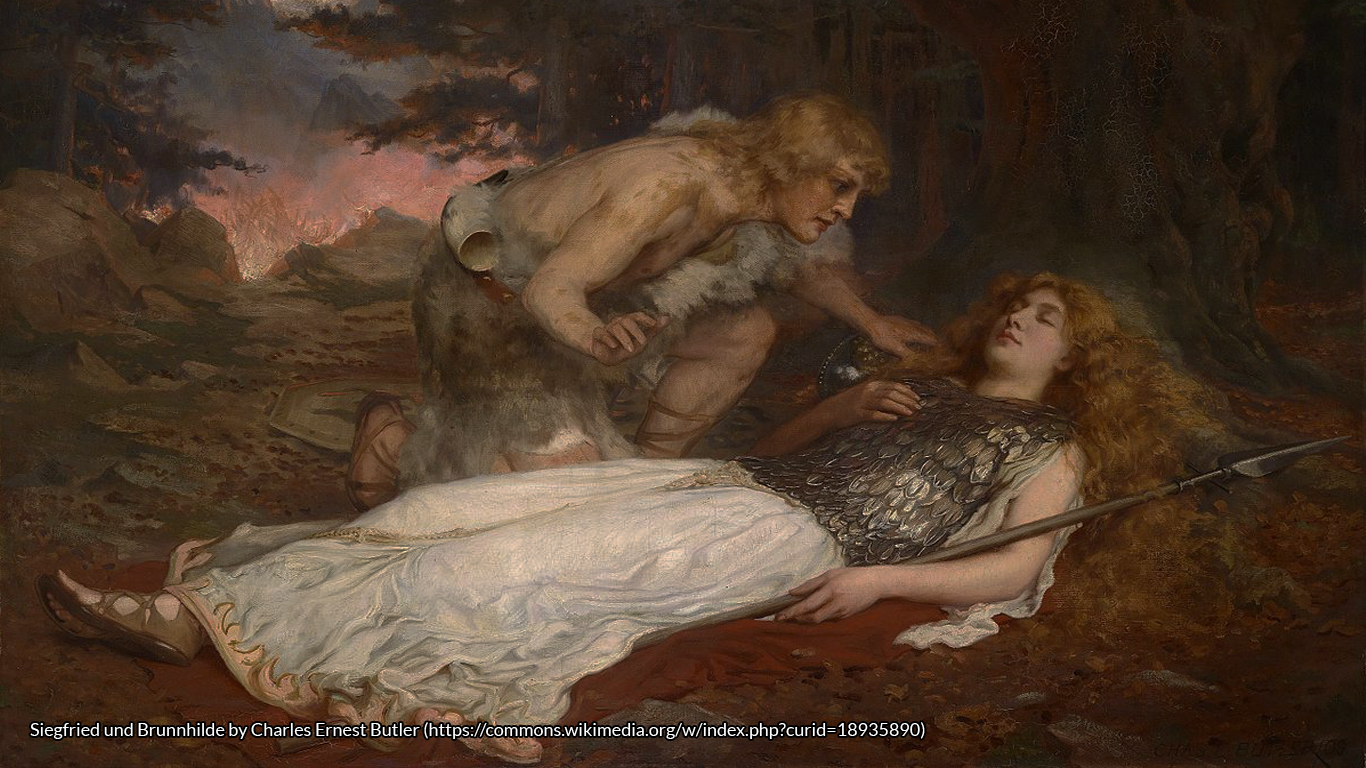

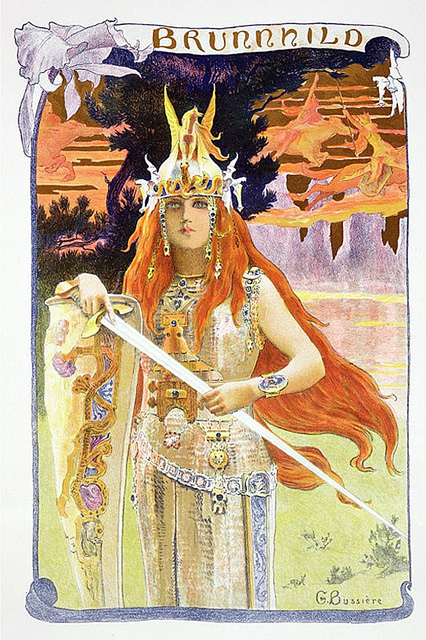

Sigurd travels on to a kingdom where he marries the princess Gudrun, and becomes close friends with her brother, Gunnar. The latter has heard tell of a beautiful valkyrie (one of Odin’s servants) called Brynhild, who is imprisoned in a fortress surrounded by supernatural fire. Gunnar persuades Sigurd to help him rescue her and make her his wife. When they reach the fire, Gunnar’s horse is too petrified to cross it. So Sigurd uses magic to transform himself into Gunnar’s exact likeness, rides his own fearless horse through the flames, enters the fortress and seduces Brynhild with a promise of marriage. To seal this, Brynhild insists on being given the ring.

After the wedding of Gunnar and Brynhild, the ring’s curse sets to work again. Brynhild soon discovers that the man who originally seduced her was not Gunnar after all, but Sigurd. Outraged by this violation, she has Sigurd murdered. Then, in a dramatic scene, she forces the ring onto Gunnar’s finger and commits suicide.

Some time later, Gudrun’s scheming mother forces her to marry the late Brynhild’s brother, Atli – the historical Atilla the Hun. He treacherously lures her brother Gunnar to his kingdom, then brutally murders him by hanging him over a pit of venomous snakes. This is the last act directly caused by the ring, for before meeting his doom, Gunnar has flung it into the depths of the River Rhine, never to be found again. However, its echoes continue to be felt: Atli himself meets a violent death by Gudrun’s hands, and her own children also suffer gruesome ends.

Read It for Yourself

The medieval texts are all fascinating, though they demand a degree of persistence to plough through. You can read them in the modern translations listed in the References below, or try these free online resources:

Prose Edda: http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/pre/

Poetic Edda: http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/poe/

Volsunga Saga: http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/vlsng/

Alternatively, you can find an accessible and authentic retelling, with comprehensive background notes, in my book Viking Myths & Sagas Retold from Ancient Norse Texts.

Whichever version you choose, afterwards take another look at The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. Then decide for yourself: was it Tolkien, or the Viking storytellers over a thousand years before him, who turned the idea of a ‘cursed ring’ into the more extraordinary story?

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Old Norse Texts

Edda by Snorri Sturluson, translated by Anthony Faulkes – The Prose Edda (J. M. Dent, 1987)

Elder Edda: A Book of Viking Lore, translated by Andy Orchard – The Poetic Edda (Penguin Books 2011)

Saga of the Volsungs, translated by Jesse L. Byock (London: Penguin Books 1999)

Other

Kerven, Rosalind: Viking Myths & Sagas Retold from Ancient Norse Texts (Talking Stone 2015),

Tolkien, J. R. R.: The Hobbit, first published 1937 (HarperCollins Children’s Books, 2013)

Tolkien, J. R. R.: The Lord of the Rings, first published in three volumes, 1954 – 55 (HarperCollins, 2007)