There is so much to say about megalithic tombs: of their function, carbon dating, about morphological typologies, and catchment areas. I could tell you about function and materiality, about labour and material costs. I could tell you about the magic that is phenomenology in recreating the prehistoric mind. At the top, there is an audio with a little about what megalithic tombs are, their landscapes and the Neolithic world. The few terms I’ve given above give an idea of what to look up later, ideas that I will try to expand on in my own blog where I have more scope to divert from our main focus: the folklore of stones, and their stories of giants and fairies. Here, I will focus solely on the stories that have been told about megaliths throughout the ages before scientific analysis unlocked their secrets for us, conjuring some of the magic that gives a tingle in the fingers when touching the cold stones of a megalith for the first time, secreted away in hidden outcrops that are often unseen, invisible to the modern world as life moves on around it. I’ll show you a glimpse of the wonder that I, personally, feel when I lie on the cold stones and ponder all the people, all the lives, that have been touched by this stark, lonely form, jutting out of the landscape as a symbol of memory, of identity, of endurance, that has crawled into the minds of those who look on it, a feeling of reaching out to touch the past that you can never shake once you have known a megalith, learned its secrets, studied its stones and gazed on its carvings in wonder, reaching out to learn the secrets of old minds.

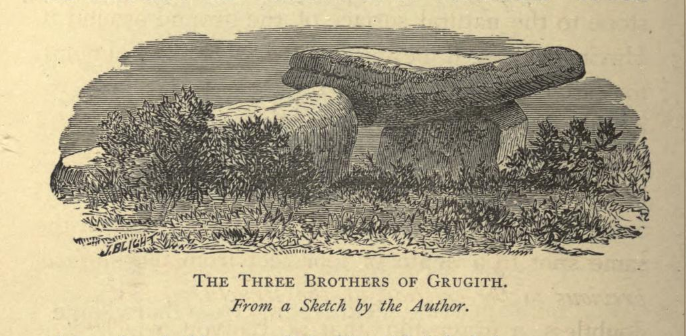

While much fairy folklore associated with prehistoric sites centres around barrows and brochs, many megaliths are linked to fairies, goblins and their counterparts, in both legend and etymology. Crucuno in Brittany is called La Roc/ze aux Fees, or the ‘stone of the fairies’ [1], and the name Moylisha-Labbanasighe, a wedge tomb in Co.Wicklow, Ireland, translates to ‘bed of the fairies’. While such names show that the fairy link to such stones has a long history, offerings were often left at tombs up until much more recent years, for instance honey cakes were left at Arthur’s Qoit [2], given ‘periodically at midnight and full moon, by maidens testing the fidelity of their lovers’ [3]. Similarly, there has been some discussion in old texts of the link between megalithic tombs and offerings to the Gruagach – a ‘type of brownie who watched over the herds, and had taken the place of a god” [4]. It was said by Worth in 1896 that the Isle of Skye was filled with these Gruagach stones, many with cup markings that were filled with milk as libations. He called it a ‘curious coincidence’ that the dolmen of The Three Brothers of Grugith, St. Keverne, Cornwall, ‘should bear those mysterious cup markings, not certainly known to exist elsewhere in the West’ [5], of which Dexter says there are nine, intended for libations [6].

More mysterious still, in Guernsey folklore, Le Creux ès Faies megalith is said to be the entrance to the Otherworld, and the ‘usual dwelling place’ of the fairies, from where they would emerge, on the night of the full moon, and dance until daybreak [7]. MacCulloch also tells of earlier legends: one where voices, presumably those of the fairies, were heard coming from the mound, another where a freshly baked cake was found in the furrows by an unsuspecting ploughman, who rushed forward for it, only to be bashed on the head for his troubles. He recounts that the site was a fairy house, and an 1896 letter from his cousin tells of a local woman’s claims that fairy pots and pans were unearthed when the locals dug down.

In Brittany, megalithic tombs are often called the caves or rocks of the fairies. One story was collected by Sébillot in 1881 from a local gardener about a megalith sited between Saint-Didier and Marpiré (Ille-et-Vilaine), and it is shown to have strange origins: ‘[the fairies] took the biggest stones of the country and carried them in their aprons; then they piled them one on top of the others to build their houses’ (my translation: [8]). Another dolmen, near the wood of Rocher in Pleudihen, was similarly made by the fairies by carrying rocks in their aprons according to the local people [8]. It’s interesting to note that, in contrast to the megaliths as homes for the fairies, a ‘white-haired farmer’ spoke of a menhir (‘peulvan’) called la Pierre Fritte, saying that the fairies erected such things for those souls who had done good in their life, and whose ashes could remain ‘safe from the malice and destruction of time’ where ‘they came at night to talk with the dead’ (my translation: [8]).

In another story from the forest of Theil, near the farm of Rouvray, a farmer tells the legend of ‘the Cradle of Fairies’. In this tale, the fairies were able to carry two great stones at a time, one on their heads, and another in their aprons, and they were so unencumbered that they were still able to spin their distaffs as they walked’ (my translation: [8]). In essence, while legends of fairies in Britain aren’t so popular for megalithic tombs, and instead are focussed around the Bronze Age and later sites, we find that fairies abound in the folklore surrounding dolmens in continental Europe, and indeed in Ireland.

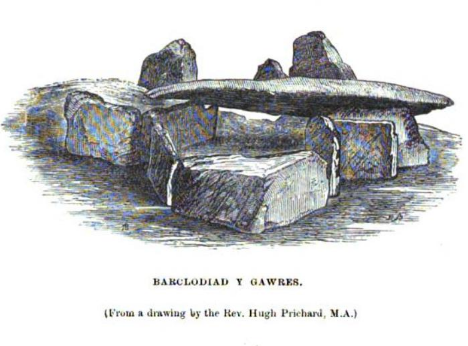

In contrast, stories of giants reach far and wide in cromlech folklore. In many stories we see the stones being lost, thrown, or dropped, for instance the Welsh tomb, Barclodiad y Gawres, means ‘apronful of the giantess’ in English [9], and there is a recurring motif of two rival giants (or often just one giant and the Devil) throwing stones, or clods of earth, at each other, for instance the Whitstones in Somerset [3]. In others, the stones are the houses or ovens of giants. Another irrepressible idea is of megalithic tombs as the beds or tombs of giants, and this is reflected in their names around the world: in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern they are Hünengräber (‘giants’ tombs’) or Hünenbett (‘giants’ beds’), while in the Netherlands they are Hunebedden. Holtorf puts the earliest association of giants with megalithic tombs back to at least the 13th century, with the mention of tumuli gigantis in 1535 by the Pomeranian historian Thomas Kantzow [10]. In fact, there is a lovely story associated with the Riesengrab megalith (‘Giant’s Grave’) in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, about a giant who plagued his neighbours to the extent that they sought to get rid of him by burying him alive. One day when he was sleeping, they dug a hole, rolled him into it and covered him in soil. When his wife found him, she went away, filled her apron with stones, and poured these around him in mourning. However, the giant got up, after what he considered to be merely a good sleep. The villagers came up with a better plan. They waited until he was asleep again, dug an even bigger hole, covered him in earth, and then piled the surrounding stones on top so he could never get up again. A translation by Ymke Mulder (after the original [11]) can be found in Holtorf’s thesis here. It’s interesting that they are also referred to as ‘beds’ in Ireland, when linked to the legend of Diarmuid and Gráinne, who eloped and each night used a different megalith as their bed. Interestingly, some consider this a reason that megaliths are visited by women to increase their chances of falling pregnant, as these are places where Diarmuid and Gráinne embraced [6].

Megaliths are still scattered in the landscape across the Atlantic Façade today, and while our modern scientific methods often seem to quash the magic that they once held for the common man, one cannot deny that standing in the presence of these magnificent stones, in the tall shadows of evening, that the echoes of these stories of fairies and giants still linger. When we marvel at their towering heights, there is still part of us that questions how, just how, people like ourselves erected such huge, roughly-hewn stones, carrying them for miles across the bleak landscape and setting them up for ages to come. And sometimes, just sometimes, we might find ourselves thinking, even today, in our modern lives of reason and rationale, that maybe there is a giant, lurking – sleeping – ever so softly under out feet, with the stones as his bed …

When old skills are lost, such as, for example, the power to set up circles of great standing stones, they become, in folk-memory, the work of giants or even gods. On the other hand, mysterious beings, of which one catches a glimpse crouching among moorland rocks or emerging from turf-covered dwellings (holes in the ground), become little folk-the fair folk or fairies. [12]

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday

1. Packard, A. S. 1891. ‘Among the Prehistoric Monuments of Brittany’, in The American Naturalist, Vol. 25, No. 298, pp. 870-890. The University of Chicago Press for The American Society of Naturalists

2. Menefee, S. P. 1980. ‘A Cake in the Furrow’, in Folklore, Vol. 91, No. 2, pp. 173-192. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

3. Grinsell, L. V. 1976. Folklore of Prehistoric Sites in Britain. Newton Abbot: David & Charles (Publishers) Ltd.

4. McCulloch J.A. 1911. The religion of the ancient Celts.

5. Worth, R. N. 1896. ‘The Rude Stone Monuments of Cornwall: Part II’, in Journal of the Royal Institution of Cornwall vol XII. Truro: Lake and Lake.

6. Dexter, T. F. G. 1932. The Sacred Stone. Perranporth: New Knowledge Press. http://www.cantab.net/users/michael.behrend/repubs/dexter_ss/pages/main_text.html (Accessed 11/07/16)

7. MacCulloch, E. 1903. Guernsey Folk Lore. London: Stock.

8. Sébillot, P. 1882. Traditions et superstitions de la Haute-Bretagne. Paris: Maisonneuve

9. Pickering, W. (1846). Archaeologia Cambrensis : a record of the antiquities of Wales and its Marches and the journal of the Cambrian Archaeological Association. London.

10. Holtorf, C. 2000-2008 Monumental Past: The Life-histories of Megalithic Monuments in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Germany). Electronic monograph. University of Toronto: Centre for Instructional Technology Development. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/245. (Accessed 13/07/16)

11. Bartsch, K. 1879. Sagen, Märchen und Gebräuche aus Mecklenburg. Wien: Braumüller. Reprinted 1978: Hildesheim and New York: Georg Olms Verlag.

12. Fleure, H. J. 1948. ‘Archaeology and Folklore’, in Folklore, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Jun., 1948), pp. 69-74. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.

Images

Copeland Borlase, W. 1872. Naenia Cornubiae, a descriptive essay, illustrative of the sepulchres and funereal customs of the early inhabitants of the county of Cornwall.

Gregorson Campbell, J. 1900. Superstitions of the Highland and Islands of Scotland. Glasgow: James MacLehose & Sons

Bibliography for An Introduction to Megaliths, Their Landscapes and the Neolithic World (audio)

Cooney, G. 2000. Landscapes of Neolithic Ireland. London: Routledge.

Joussaume, R. 1985. Dolmens for the Dead. London: Guild.

Lynch, F. 1997. Megaliths and Long Barrows in Britain. Buckingham: Shire.

O’Kelly, M. J. & C. 1989. Early Ireland: An Introduction to Irish Prehistory. Cambridge: University Press.

Whittle, A. W. R. 1996. Europe in the Neolithic: The Creation of New Worlds. Cambridge: University Press.