Each autumn thousands of migrant redwings, fieldfares and bramblings visit the UK from their Scandinavian breeding grounds, spending the winter among our fields and woods. Despite their long-standing annual arrival there appears to be a lack of folklore associated with these species.

Fading afternoon on All Hallows’ Eve and a mist is rising over the expanse of meadow that breaches the broad gap between the trees. The late-afternoon sunlight is weak, but gives an impressive vividness to the wood’s turning leaves. Thin, high-pitched calls come from the hawthorns that border the track, as dark silhouettes shoot away in front of me. Some move tentatively ahead, one bush at a time, while now, as I press further on, they vacate their cover en masse, forming a sizeable flock that passes above the field on its way to the pines opposite. Sleek and elegant in flight, they are redwings – members of the thrush family and one of Britain’s commonest winter-visiting songbirds.

Watching these migrants file away to roost in the woodlands of west Norfolk, newly arrived from the forests of Scandinavia and perhaps even Russia – the places where they will have bred this past summer – I wonder about the folklore that surrounds them. What we do we know about the birds themselves? Well, apart from a relatively brief colonisation of northern Scotland as a breeding bird during the earlier part of the twentieth century, the species has been confined to the UK as an annual and conspicuous winter visitor to our countryside as long as observers of the natural world have been recording such things (the first mention in print of the name appears to be in Francis Willughby and John Ray’s 1678 The Ornithology). Given this though, I am surprised when browsing Francesca Greenoak’s British Birds: Their Folklore, Names and Literature (1997) that there are not more stories about a bird which, undoubtedly, would have been well-known to country people for centuries as a marker of the arrival of late autumn and the oncoming winter.

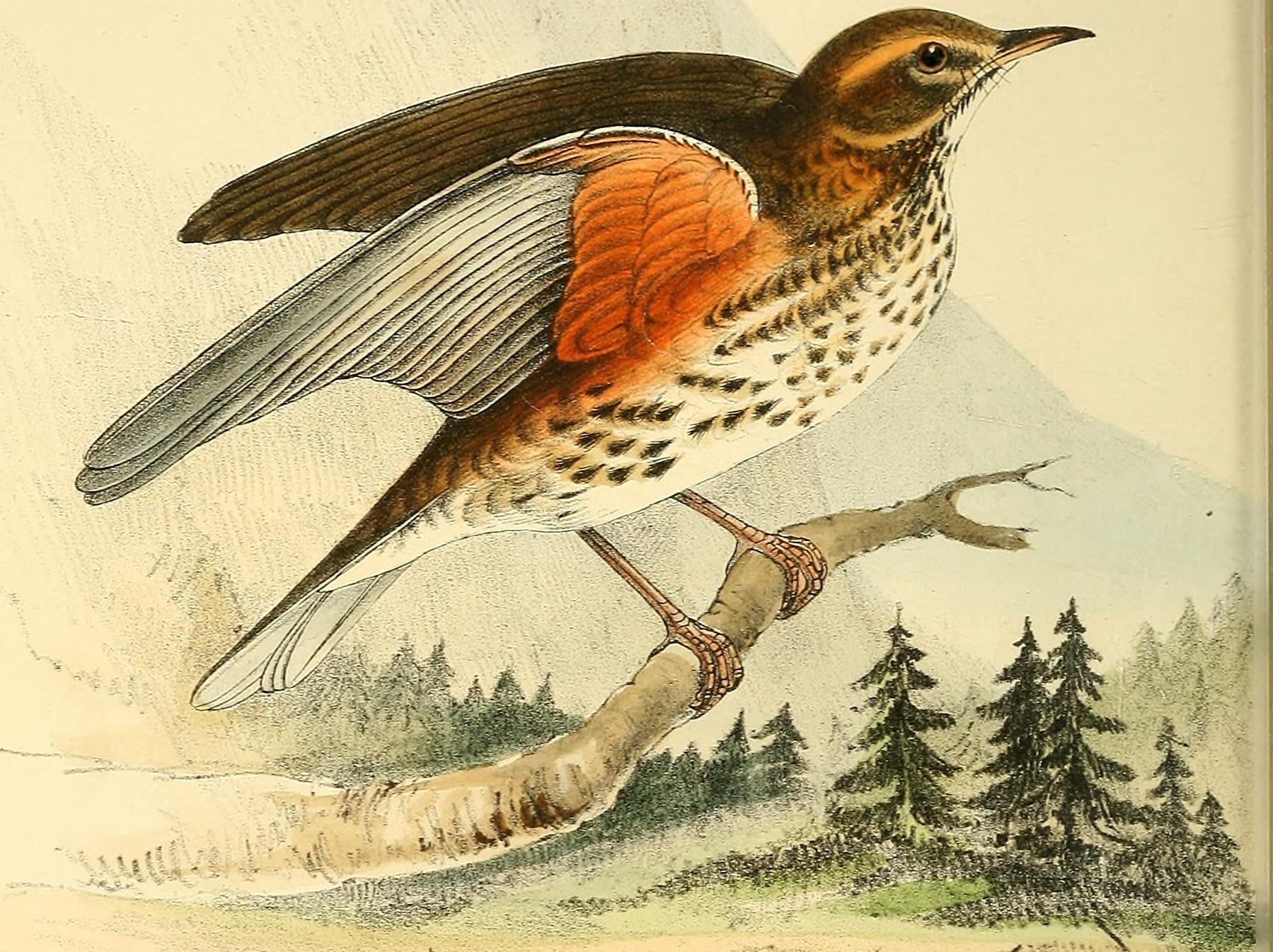

The name ‘redwing’ itself is a simple descriptive one, describing the orange-red wash on the sides of this elegant little thrush – though perhaps as noticeable a feature is the distinctive cream stripe that runs like a pale brow above the eye. A Short and Succinct History of the Principal Birds Noted by Pliny and Aristotle, published by Dr William Turner in 1544, refers to the species by the German name ‘weingaerdsvogel’ or ‘vineyard bird’, leading to the English ‘wyngthrush’. Given the general lack of vineyards in Britain, this later became corrupted to be ‘wind thrush’ (Somerset) or ‘windle thrush’ (Devon), according to Greenoak. Despite these few archaic names my sources – including Mark Cocker and Richard Mabey’s excellent Birds Britannica (2005) – offer nothing in terms of any potential folklore surrounding the species, though there are a number of stories associated with our resident song and mistle thrushes. (For instance, while researching my 1940s-set novel The Listeners I was taken with the old mistle thrush name of ‘stormcock’, a reference to the species’ apparent willingness to sing during or just after stormy weather.) An internet search does come up with something, however, a brief mention of the ‘herring-spear’ – the sound the redwing makes while passing overhead and which, according to A Dictionary of the Kentish Dialect and Provincialisms: in use in the county of Kent (1888), tends to coincide with the herring-fishing season.

Another species of Scandinavian thrush is indelibly associated with the redwing, since both arrive at the same time and from broadly the same places, and often end up forming large mixed flocks here in the UK. The fieldfare is a larger bird than the redwing and more obtrusive with its loud cackling flight calls and grey-splashed plumage. Chaucer recorded the species in his 700-line poem The Parlement of Foules (c. 1382), where he describes them as ‘the frosty feldefares’; later poets including John Clare and Matthew Arnold also mention the species, Greenoak states, before going on to explain that ‘fieldfare’ literally means ‘the traveller over the field’, a phrase I like very much. Again though, there seems a distinct lack of associated lore regarding the bird, though finally after much searching I find a short weather reference in the October section of Allan Jobson’s A Suffolk Calendar (1966): ‘The early arrival of the fieldfare is considered a sure sign of a hard winter.’

Walking onwards, the mist is rising higher as I skirt a reed-fringed stream. In the alders bordering the watercourse I spot a flock of finches backlit by the dying light. They fly a short distance across to some birches, where I manage a proper look at them: they are mainly bramblings, another winter visitor to the UK from Scandinavia. Up close they are like muted, autumnal-tinged chaffinches, with their mixture of buff and orange highlights and striking white rump making them one of my favourite birds on the odd occasions I am lucky enough to happen upon them. These ones are calling quietly to each other as they feed among the still heavily leaved birch branches, occasionally perching out in the open where I can enjoy them properly. The name itself probably derives from the bramble bushes where the species was thought to roost (Greenoak), though W. B. Lockwood’s The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names (1984) suggests a derivation from the word ‘brandling’, meaning a creature with brindled (tawny-streaked) markings, which is certainly appropriate given the bird’s appearance. The great 18th-century ornithologist Thomas Bewick referred to the species as the ‘mountain finch’, though the name has not persisted except in its scientific name montifringilla.

Two carrion crows perch silhouetted at the top of a pine as small parties of redwing continue to fly above my head, their whistles perforating the dampened silence of the gathering darkness. Given the lack of lore that seems to exist around these winter visitors I have to imagine my own stories about the mysteries of their annual arrival: perhaps they burrow out from beneath the leaf litter of the late autumn woods; or more likely – due to their tendency to migrate on cloudless nights, when they reveal their unseen overhead presence with their distinctive flight calls – they have some sort of strange arrangement with the moon, perhaps emerging from the moonlight itself on autumn nights when our satellite is at its fullest and brightest in the sky. And might the now-roosting bramblings be hatched from fallen beechmast, since the species in winter generally shows such a marked feeding preference for that particular tree (in central Europe it’s not unknown for wintering flocks in their millions to descend temporarily upon a place until the locality is entirely stripped of its beechnuts)?

Perhaps such stories did once exist and have been forgotten. Or has the generally unobtrusive nature of the redwing and brambling led to a lack of associated folk tales (though how would this account for the paucity of tales pertaining to the noisy fieldfare)? Is the same true in their Nordic nesting grounds too, I wonder? (In Stockholm for instance, Scandinavia’s largest city, the fieldfare is a ubiquitous breeding bird, commonly seen around parks and garden in much the same way as the blackbird is here in the UK – given that, it would seem odd that there isn’t extant Swedish folklore about the species.)

I walk back towards my car, the faint whistles of redwings still passing above. Travellers over the darkness.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References and Further Reading

Cocker, Mark and Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London, Chatto & Windus.

Greenoak, Francesca (1997). British Birds: Their Folklore, Names and Literature. London, Helm.

Jobson, Allan (1966). A Suffolk Calendar. London, Robert Hale.

Lockwood, W. B. (1984). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. Oxford, Oxford University Press.