A couple of month’s ago I happened upon a copy of A Dictionary of British Folk-Lore by Alice Gomme, a classic work on childlore.

A couple of month’s ago I was lucky enough to find a slightly worn-looking antiquarian book in one of my local charity shops. As I have an interest in folklore, the faded gold-gilt title on the book’s burgundy spine was instantly appealing: A Dictionary of British Folk-Lore, Part I: Traditional Games, Vol. I by Alice B. Gomme. I happily paid the few pounds asking price, went home and began to delve into this fascinating late-Victorian title.

Born Alice Bertha Merck in London in 1853, the daughter of a master tailor, according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography we know little of Alice’s life until, aged 22, she married on 31 March 1875. Her husband, (George) Laurence Gomme, was a keen folklorist and prolific author on the subject, and later President of the Folk-Lore Society – he was knighted in 1911 for his services to London County Council, whereupon Alice became Lady Gomme.

Alice Gomme’s reputation as a folklorist has not, until recently, been fully recognised. In their preface to the seminal The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (Opie and Opie: 1959), the authors note that Alice Gomme’s classic two-volume text has a rural bias, and that the book was already out of date when it was published, largely relying on distant recollections from Gomme’s correspondents. This seems to me though to be a little uncharitable, given the obvious depth of research that jumps off the pages when browsing through the first volume (covering Accroshay–Nuts in May) that I’m currently holding.

In any case, to me, as an interested dabbler in the field, the single volume I own has opened up a fascinating path into the subject of childlore. And in this short essay I’d like to share a few of the ‘tunes, singing-rhymes, and methods of playing’ that this remarkable woman – mother, folklorist, active suffragette, lecturer and writer, and expert in Elizabethan stage methods – collected towards the end of the Victorian period.

Oldies but goodies

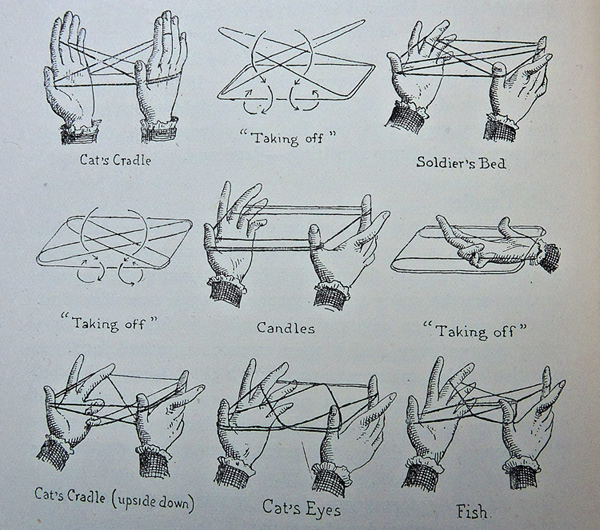

Flicking through the comfortingly thick and musty-smelling pages, it’s interesting that many of the games are ones – or at least variants of – I remember from my own childhood. As well as universal favourites like ‘Cat’s Cradle’ (a game, Gomme notes, ‘known to savage peoples’) and ‘Blind Man’s Buff’, Gomme dedicates several pages to ‘Hide and Seek’, surely one of the classic, perennial childhood amusements. What, though, I had no idea about was the large numbers of associated localised rhymes and rules surrounding how it was formerly played. In Scotland for instance, Gomme states, the game was called ‘Hopsy’ and played only by boys, while in Leicestershire it was called ‘Hide and Wink’, and in Dorset ‘Hidy Buck’.

In a Proustian moment I now recall ‘British Bulldog’: I can’t remember exactly how we played the game, but I do recall it having a tendency towards increasing roughness, leading to it eventually becoming banned at my Lincolnshire primary school. Sadly though, it doesn’t appear to be included in Gomme’s book – at least not under the name I remember. And at this point the limitation of owning only Volume I becomes apparent, as I now also have a desire to check if ‘Stuck in the Mud’ (which my partner recalls as being called ‘Stick-in-the-Mud’ at her Leicester school) also appears in Volume II – another game that suddenly comes back to me out of nowhere.

Esoteric games

Reading Gomme’s book alongside Iona and Peter Opie’s The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren, it strike me just how mysterious childlore is. The Opies, in particular, stress how certain games and rhymes have been around for centuries, evolving and travelling between different areas of Britain (and beyond). And yet, the means by which these childhood customs arose and were later propagated seems elusive. Many of the traditions that Gomme describes seem equally hard to pin down from her brief descriptions. I’m drawn to the game of ‘Bandy-hoshoe’, probably because she states it is a common game in my home county of Norfolk. And yet, her brief description leaves me little the wiser about what actually took place during the play, though it appears to be a variant on hockey or golf – something, at least, that involves hitting a ball or similar object with a crooked stick.

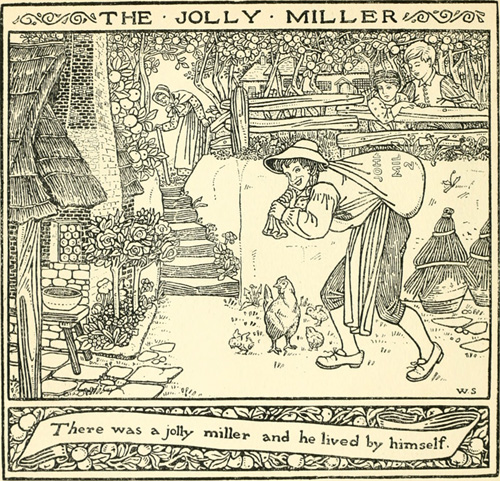

Alongside this unknown prototype sport, are listed many more localised games involving rhymes, dancing, rituals, or just plain nonsense. Many are equally hard to get a handle on: ‘Dropping the Letter’ is an undescribed Suffolk boy’s game; ‘Jackysteauns’ is a game played by Cumbrian schoolgirls with pebbles; ‘Jolly Miller’ appears to be a verse game played in a circle, although the contributor, a Miss Keary, says: ‘How it ends I have never been able to make out; no one about here seems to know either’; ‘Minister’s Cat’ is a word game recorded from Gloucestershire and North Lincolnshire; while the Sheffield game of ‘Nip-srat-and-bite’ is delightfully described as ‘a children’s game, in which nuts, pence, gingerbread, &c., are squandered.’

Childhood games in the 21st century

There seems to be a widespread fear among older people – understandable, I suppose given the way social media and new technologies change the way our children play and interact – that traditional games are disappearing. In April 2006, for instance, the Daily Express carried the headline ‘Skipping? Hopscotch? Games are a mystery to the iPod Generation’. However, fascinating recent research on the subject by the Universities of London, Sheffield and East London and the British Library seems to conclude that traditional children’s games are still very much alive and well (see: http://projects.beyondtext.ac.uk/playgroundgames/index.php)

Interestingly, while reading Alice Gomme’s book, my neighbour’s five-year-old daughter introduced me to a modern-day piece of childlore as I was gardening one afternoon. Called ‘Chicken or Hen’, the game, which she tells me she plays with her friends at school, involves picking a flower (or seed head) and then presenting it to the recipient, who has to decide whether the bloom best resembles a chicken or hen.

‘I don’t understand how it works!’ I protest, trying to read too much into the game’s simple rules, which only seem to require the briefest of identifications of said chicken or hen – albeit not an entirely obvious binary decision to make!

Gomme’s book now held in front of me, I turn to the letter C, but sadly the game isn’t listed there (nor in Opie and Opie); I try Google too but find no mention, which leads me to suppose it’s a local game yet to lay down deeper roots. And yet, given the vagaries of how these games appear to spontaneously arise and mutate, it seems entirely possible that in years to come ‘Chicken or Hen’ will, by some strange agency, take a foothold in the infant schools of Norfolk and beyond…

I look at the seed head I’ve been presented with.

‘Chicken,’ I say.

My neighbour’s little girl laughs at me like I’ve just said the most ridiculous thing.

‘It’s a hen!’ she says.

Alice Gomme’s A Dictionary of British Folk-Lore: Part I is a classic work on traditional games, which deserves greater attention today. It offers a fascinating insight into the esoteric world of childlore, and presents a compelling snapshot of the late-Victorian era.

Beyond Text (2009–2011). Children’s Playground Games and Songs in the New Media Age. Collaborative research project. See: http://projects.beyondtext.ac.uk/playgroundgames/index.php

Boyes, Georgina (2001). A Proper Limitation: Stereotypes of Alice Gomme. Musical Traditions Internet Magazine. See: www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/gomme.htm [accessed 29 May 2016].

Gomme, Alice (1894). Dictionary of British Folk-Lore, Part I: Traditional Games. Volume I: Accroshay–Nuts in May. London, David Nutt.

Gomme, Robert (online edn, May 2006). ‘Gomme, Alice Bertha, Lady Gomme (1853–1938)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, Oxford University Press. See: www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38616 [accessed 29 May 2016].

Gomme, Robert (2004). ‘Gomme, Sir (George) Laurence (1853–1916)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford, Oxford University Press. See: www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38616 [accessed 29 May 2016].

Opie, Iona, and Opie, Peter (1959). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford, Clarendon Press.

University of Sheffield (2012–2017). Childhoods and Play. British Academy Research Project. See: http://www.opieproject.group.shef.ac.uk/