Enter the Boggart

The story takes place some two hundred years ago, on the wild edges of a tiny Lancashire village. A young boy, Sam, has been compelled to attend a Methodist service. Bored with the religious burblings of his elders, Sam, with other children, sneaks out into the night-time fields, and there runs around, trying to escape the hum of prayers. In this thrilling dash Sam sees one of his mates, Bill, tearing ahead of him in the dark. Sam trots up shouting, but Bill strangely does not react. Sam pushes forward and overtakes his friend, looking back in triumph. It is not, though, Bill. Cue creepy music. The ‘boy’ has a dreadful decayed face. Terrified, Sam sprints away. ‘I now ran in earnest to get rid of him; but on looking back, saw he was within a few yards of my heels.’ Through the dark fields the pursuit continued between this fragment of nightmare and the child.

The boggart, for so monsters like this were known in Lancashire in the nineteenth century, was now almost upon Sam, its feet sweeping effortlessly over the ground: ‘I know not how, but at an incredibly swift pace’. The hunt ended only when Sam came within sight of the chapel and heard prayers. Perhaps, like many supernatural beings, Sam’s pursuer could not abide Christian words and symbols; or perhaps the boggart had come to the edge of its territory – such beings were often said to have their own ‘patches’. The terrified boy had, in any case, escaped. Chastened by his ordeal, Sam sneaked into the building – breathing we might imagine rather heavily – and found himself kneeling in prayer next to the real Bill. Indeed, the adult Sam, remembering some twenty years after his brush with the impossible, recalled that, having knelt in chapel, he had ‘prayed more really in earnest’ than ‘during a long time before’.

We know this story because later in life Sam became a notable writer.

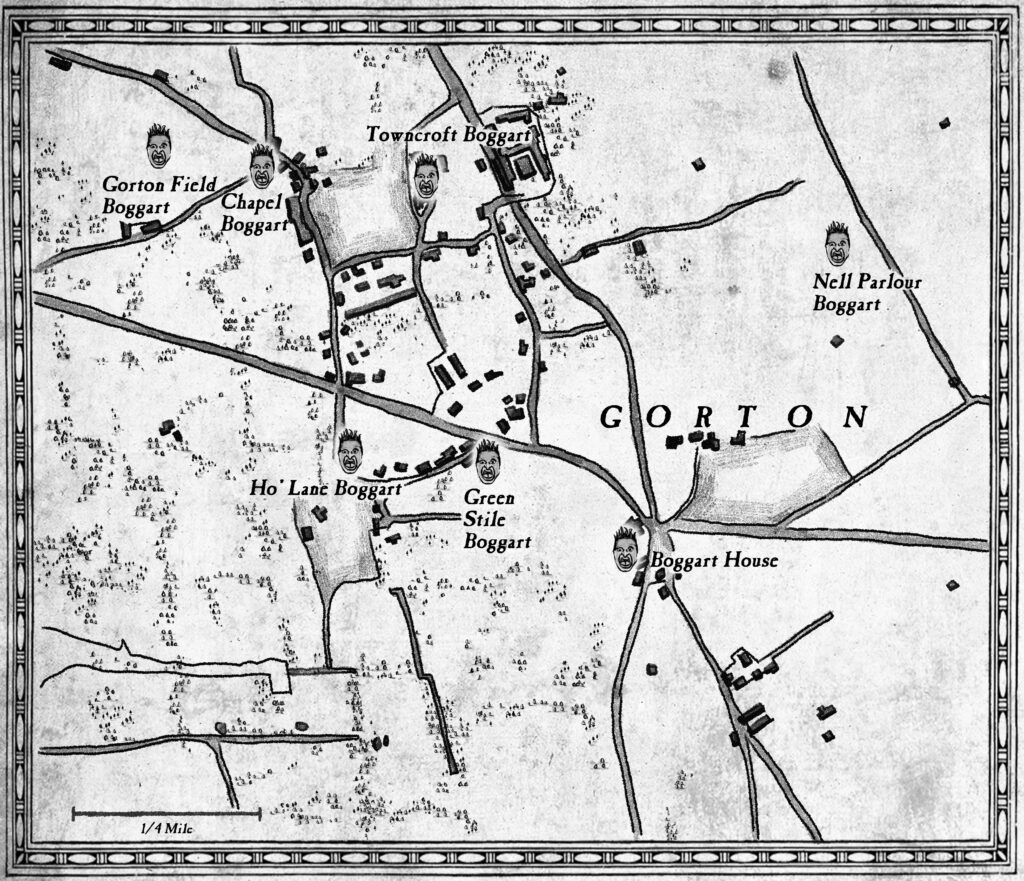

Samuel Bamford (1788-1872) was a Lancashire weaver who got caught up in the reform movement of the 1810s. He was present at the slaughter at Peterloo, was subsequently sent to prison and he, later, made a living (of sorts) by writing books. His close encounter with this north Manchester boggart appears in Passages in the Life of a Radical. Sam Bamford coming of age in a poor family in Middleton knew a great deal about boggarts and he records several traditions.

Bamford himself had lived on the edge of Boggart Hole Clough, the park on the northern edge of Manchester, where you can still catch a whiff of boggart fear.

But What is a Boggart?

I became fascinated by boggarts about a decade ago. I had grown up in a very similar countryside to that which Sam Bamford and his friends ran through. I was, thinking back, intoxicated by the idea that these places had their own ‘presences’. But I was also confused about what boggarts were supposed to be. If I turned to the fairy and folklore dictionaries, I learnt that a boggart was a type of house goblin or perhaps, at a stretch, a poltergeist. This was confirmed by late Victorian children’s stories, by the girl guides movement (where a boggart was a mischievous imp) and by popular culture: the boggart’s recent outings in post-war confirms this, be it Susan Cooper, William Mayne or even J.K. Rowling.

But in the nineteenth-century sources I read, everything from newspapers to learned studies, the boggart was so much more than this. Ghosts were routinely called boggarts: in fact, many people in the north of England used just that word to explain when asked what a boggart was. Phantom dogs and shape-changers were called boggarts. Jenny Greenteeth (the murderous undine who lurked in ponds) was a boggart. Indeed, every imaginable solitary supernatural figure was routinely called a ‘boggart’: angels and fairies were the only supernatural things not to be so addressed. The boggart was not a type of supernatural creature, it was an eco-system of the solitary, ambivalent and impossible.

A boggart, then, could be a child with a rotting face (to think of Sam Bamford’s experience), it could be a grumpy house spirit or it could be a will o’ the wisp. We had boring ghosts and we had the utterly baroque: the female spirit, say, who kept her head in a basket and who would hurl it after night-time walkers. In Boggartdom, the places where the word was used, it denoted anything that was supernatural and creepy: this was the case in Lancashire, the West Riding, and parts of Cheshire, Nottinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Staffordshire and southern Cumbria. If I had to translate ‘boggart’ into standard international English I would use the word ‘bogie’. The only problem is that ‘bogie’ suggests something imaginary, something invented in English today: think of the ramifications of ‘bogie-man’. In the communities where ‘boggarts’ was used these beings were treated as a real and present danger. That is not to say that everyone believed in boggarts, but enough did to keep a network of places electrified with tales of dismal death, hauntings and encounters.

The Boggart Census

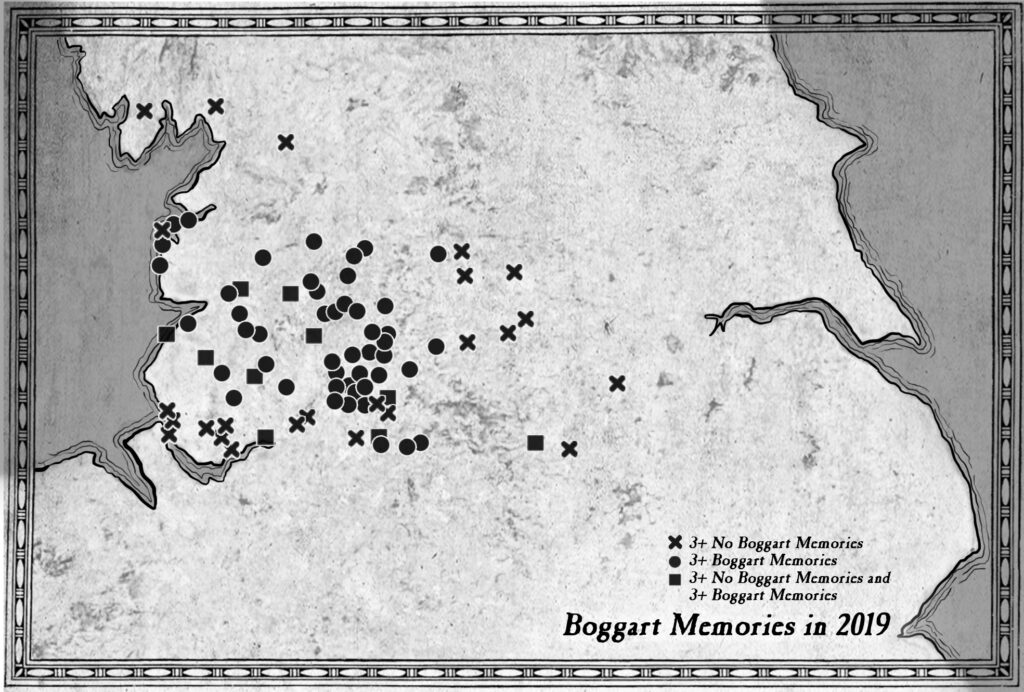

It was wonderful reading about the boggart in the nineteenth century, but did, I wondered, boggarts survive today in their old heartlands? Were there not perhaps some out of the way villages and valleys where locals still terrified each other with tales of boggarts? To this end, I launched, in 2019, the Boggart Census, in part on this website. After some initial success in online publications, I took the fight to social media. I continued at a good pace until I had gathered in about 1,200 memories, the vast majority from Boggartdom and the vast, vast majority from people older than fifty. I was amazed by how many people in their nineties wrote to me on Facebook.

I was interested in anyone who had come across the word ‘boggart’. About a third of respondents said ‘no’ they had not heard the word. These were very short entries… But negatives were important. There were also many people who talked of old boggart beliefs or boggart phrases that they’d grown up with: for instance, the wonderful ‘taken boggart’ for a horse that became skittish or worried. Grown children had often heard the words only once. But the trauma of seeing a horse race down a street had fixed it in their mind even though they had no idea what ‘boggart’ meant. There were also memories of boggart stories and boggart superstitions: there were even some boggart sightings. I particularly enjoyed the Boggart of Towneley Hall chasing some adolescent boys through its grounds on a snowy night!

For me the most fascinating thing was the difference between communities within Boggartdom. In some places boggart memories have all but died, even in old boggart strongholds like Bradford. In others boggarts remain a memory among some of the elderly. Then there are several extraordinary places where the old-fashioned boggarts have survived and are still talked of today. Seventeen responses came, for instance from New Mills on the Cheshire-Derbyshire border. Of these, sixteen were about supernatural boggart beliefs. Eleven responses came from the small town of Longridge. Nine of these included references to boggarts in local families and traditions; the other two respondents knew what boggarts were but had not grown up with them.

The Last of the Boggarts

Not only was the word ‘boggart’ used but it was also, in these places, the older sense of boggart that had persisted: any supernatural being rather than the modern fantasy house fairy. In fact, a number of respondents said (often apologetically) that they had been told by their parents that boggarts were ‘ghosts’ or that Jenny Greenteeth was a type of boggart. This runs against the grain of everything that folklorists tell us, but it happens to reflect nineteenth-century usage.

There were also some fascinating survivals. I had come across, in my work on Blackburn, a poorly-sourced 1887 reference to a local terror called the Pell Mell Boggart. A man who had grown up in Blackburn in the 1960s wrote in to say: ‘My dad told me there was a boggart in Pleasington called the Pall Mall boggart… He heard it from my grandma when he was a child’. Here Pell Mell has been jarringly assimilated to a high-end address from the British version of the Monopoly board!

I had likewise come across, in a sex abuse came from 1867 the phrase ‘making boggarts’. Two girls, one of whom was attacked by a man, had been ‘making boggarts’ in the north Lancashire countryside. I had never been able to understand what was meant. A contributor, again from Blackburn solved the problem. ‘My mum used to say “stop making Bogarts” meaning stop making a fuss. She is in her eighties and from Blackburn. I’ve just asked her about it, she says boggarts meaning “trouble.”’ This sense of the phrase fits in the context of the 1867 case.

A third example comes from the old West Riding. A Calderdale newspaper from 1889 had the mysterious phrase: ‘In and out like the Fernla boggart’. This mystified me, though British folklorist John Widdowson suggested that it meant in and out of the house. John was right. This response came from nearby Haworth. ‘But, as children, if we were running in and out of the house a lot, my grandmother would say “ee!, you’re in and out like Butterfield Boggart!” And despite asking around I’ve never been able to find out who “Butterfield Boggart” was!’ The boggart has changed but the sense is the same.

Exit the Boggart

I published, in February, two works (one free) that mark the end of my association with the boggarts: this article is, for me, something of a wake. First, there is The Boggart: Folklore, History, Placenames and Dialect with University of Exeter Press. As an early reviewer said to me: ‘it is a big book with lots of maps’ (some of them are included here). It is also the first volume in a new series that Davide Ermacora and myself will be editing on folklore and the supernatural for Exeter. The second book is The Boggart Source Book. This is a print on demand volume. It can be either ordered as a physical source or downloaded as a free pdf (it is just a click away). It contains three source sets: first a selection of nineteenth-century newspaper articles on boggarts; second, a list of boggart placenames; and third the Boggart Census in its entirety.

For now, thanks to all #FolkloreThursday readers who contributed to the Boggart Census!