The Japanese raccoon dog or tanuki, a shape-shifting, hedonistic and jovial trickster, has always lived in the borderlands between human settlement and the wilderness – liminal, shared spaces not quite of this world, and not quite of the other. Its complex folkloric history is also the story of the uneasy and unreconciled relationship in Japan between modernity and nature, progress and tradition.

On Friday 3rd May 1889, an exceedingly odd story was soberly reported in the Tôô Nippô, a popular regional newspaper in Meiji-period Japan. It concerned an evening steam train travelling from Ueno Station in Tokyo to Okegawa, a shukuba (lodging town or post station) on the Nakasendō (Central Mountain Highway), one of the old principal routes to Kyoto:[1]

“Just before arriving in Okegawa…a steam train that had left Ueno encountered another train, with its whistle a-blowing, advancing along the same tracks from the opposite direction. The train driver was surprised; he hastily reduced his speed and blew his own whistle wildly.

The oncoming train did the same, continuing to toot its whistle repeatedly. However, whilst it initially had appeared very close, it did not seem to come any closer. When the driver fixed his eyes on it, the train seemed to be there, but it also seemed not to be there – a figment – it was very unclear, so he increased his speed to the point that he should have crashed into the other train. But that other train just disappeared like smoke, leaving not one trace.

But where it had been, two old tanuki [raccoon dogs 狸]… were found lying dead on the tracks, having been run over. Thinking they were terrible nuisances and now they would get their comeuppances, the driver skinned them and used the meat for tanuki soup. What a surprise that such a thing could occur these days, during the Meiji period.”[2]

This strange account, framed as fact in a reputable newspaper, pinpoints the moment when folklore and modernity spectacularly collided in the Japanese imagination. The thundering steam train, symbol of industry and progress, literally mowing down the magical tanuki, emblematic of the ancient oneiric worlds of the deep inaka (countryside) through which the new railroads were blazing. How, asks the reporter, could this sort of rural witchery even happen in the bright new days of Meiji Japan?

Whilst very much a real animal – a furry fox-like canid with a masked visage resembling that of a raccoon, hence the usual, but zoologically inaccurate, translation of raccoon dog – the tanuki was also defined as a supernatural creature or yōkai.[3] Together with the similarly dual figures of the fox (kitsune 狐) and badger (mujina 貉), with whom they were frequently comingled, their stories and even names interchangeable, tanuki were the tricksters, shape-shifters and illusionists of medieval and early modern Japan.

This peculiar ability to magically transform and bewitch and befuddle humans was rooted in the liminality of their habitat and behaviour. Tanuki had always flourished in the coppiced forests of the satoyama (里山), the managed borderlands on the periphery of human settlement between farmland (sato) and the mountains (yama). The ancient satoyama landscape has a particular emotional resonance in Japanese culture, representing the old traditional, rural Japan, where the relationship between nature, human culture and the spirit world was in a state of time-polished harmony. The tanuki, kitsune and mujina who inhabited its woodlands lived alongside the villagers, but, glimpsed rarely or from a distance, were also part of a realm of magic and strangeness which underpinned the natural topography, rich with supernatural beings and strange tales.

In the misty mountain peaks, high above the farms and rice fields, guarding gateways to the otherworld, lived a strange cast of supernatural beings: bird-like tengu (goblins), sennin (immortal wizards), shiratori (magical white birds) and tennyo (divine women), whilst deep within the wild and inaccessible recesses of the mountain (okuyama 奥山), dwelled yamabito (mountain hermits), yamanba (mountain hags) and oni (demons). But it was from the woods at the mountain base, the transitional land between the true wilderness and the homely village, where tanuki, foxes, badgers, snakes, monkeys, rabbits and wild boar resided, that the richest body of folk tales emerged.[4]

Originally conflated with folklore surrounding the sinister figure of the Chinese fox, imported with monks and diplomats during the Asuka Period (538-710), the tanuki began folkloric life in Japan with a fierce, misanthropic malevolence. They caused illness and insanity, shape-shifting into a myriad of human and supernatural characters, and casting illusions to lead humans into perilous and often fatal situations. Communities became so petrified of their ominous nature, that one of the first citations of tanuki in the official record, from 702, is an stern edict against the increasingly popular practice of smoking kori (狐狸 a character combination meaning both tanuki and kitsune) out of their burrows, which were often located in dim forest graveyards, suitably preternatural and liminal sites.[5]

A short story (setsuwa 説話) from the 13th century describes a devout hermit, living deep in the mountains, who begins to receive strange nightly visitations from Fugen, the Bodhisattva of Good Conduct, on his moon-white elephant. Overwhelmed by these divine visions, the hermit invites the local hunter who brings him hot food from time to time, to stay late one evening to bear witness. As expected, the ghostly outline of Fugen appears, his elephant luminous in the dusk. The astute hunter, however, is highly suspicious – why would Fugen appear to him, a highly impious slaughterer of animals? He fires an arrow straight at the apparition, it vanishes and an eerie crashing noise resonates through the dark trees. The next morning, they follow drops of blood through the undergrowth to the bottom of a ravine, where they find a tanuki lying dead with an arrow piercing its heart.[6]

Despite its rootedness in folk traditions, the tanuki is rarely represented in visual and literary culture before the politically-stable calm of the long Edo period (1615-1868), when an explosion of oral and written stories began to explore its antics and define its attributes and iconography. Over the centuries, it had lost much of its baleful persona, acquiring a happy-go-lucky Falstaffian rascality compared to the more sharply cunning and coolly sophisticated kitsune. While the fox was very rarely outwitted, the buffoonish tanuki often ended up exposed or slain by canny humans.

Supernatural tales of its shape-shifting and illusory skills abounded during this period, with the tanuki transforming into an eclectic cast of early modern characters. Beautiful young maidens who vanish in the morning after a night of passion, leaving their human lovers nothing but a pile of muddy, rotting leaves in their stead. Homely farmer’s wives. Burly drunkards swirling punches and smashing all before them in roadside inns. Terrifying one-eyed hags lurking by dark forest paths and, most anarchic of all in the rigid world of Shogunal Japan, fierce-browed government officials, pestering householders with imaginary tax demands. In 1795, one Nagasaki tanuki even transformed into a well-heeled samurai and sneaked into a brothel for a night’s extravagant carousing, his gold turning to dry leaves the next day.[7]

Sometimes, on cool autumn nights, deep in the forest, the traveller or home-coming woodsman might even hear mysterious music drifting through the trees, the sound of tanuki drumming on their big, berry-stuffed bellies.[8]

Arguably, the tanuki’s favourite disguise, however, was that of a rotund Buddhist monk (a transfiguration called tanuki-bōzu 狸坊主). Usually depicted sitting on a cushion and beating the Buddhist wooden drum called a mokugyo 木魚 (fish gong), the tanuki-bōzu often lived in burrows underneath temples and particularly loved to deceive the incumbent priest-scholars with its profound knowledge of the Buddhist sutras. Like the Western European folk fox, Reynard, in his priestly disguise preaching sanctimoniously at geese and chickens, these tanuki served to deflate religious pomposity and hypocrisy, as well as befuddle congregations.

One account tells of a shōya (village headman) named Heigo, from Bunkokuji, a rural village in the old province of Bushū, who was visited by an extremely convincing tanuki-bōzu, who professed to be a monk from the famous Daitokuji temple in Kyoto. He mimed that he was under a vow of silence so could only communicate by written notes. Heigo felt deeply honoured that such a venerable and scholarly guest should condescend to visit his insignificant village. He invited the monk to stay with him and pampered and fed him as an important guest.

However, the more Heigo looked at the monk’s handwriting, the more suspicious he became. Something was off. The scroll haphazardly mixed calligraphic and printed scripts and contained peculiar cursive flourishes and quaint grammatical errors. It suddenly dawned upon Heigo that this was precisely the sort of writing that a disguised tanuki would produce. When Heigo awoke the next morning, the monk had completely vanished, but outside, on the dusty road, lay the bloodied dismembered body of a tanuki, fur ripped to shreds by a pack of village dogs.[9]

The tanuki’s transfigurations were not limited to humans and Buddhist deities like Fugen, however, they also enthusiastically metamorphosed into inanimate objects. They blazed across the night sky as fiery comets, hid in plain view as stones and old trees, froze convincingly as statues and confused travellers at night as flickering lanterns. They could even turn into everyday household objects.

In Bunbuku Chagama (分福茶釜 ‘Lucky Tea Kettle’), a tale popularised by professional storytellers (rakugoka 落語家) in the 17th century, an impoverished old woodsman saves the life of a wounded tanuki and to thank him, it transforms into an iron tea kettle, which he gratefully sells for a few coins to the head priest at the Morinji Temple, in the old castle town of Tatebayashi near Edo. However, being scoured roughly by the monks and regularly thrust over a blazing fire to make endless cups of tea was too much for the tanuki, and in a rush to transfigure back, the elegant tea kettle sprouted furry brown legs and raced out of the temple all the way back to the kindly woodcutter’s hut. The unlikely pair became both firm friends and exceedingly wealthy, touring the countryside to great acclaim with a thrilling act in which the tanuki performed acrobatics in his kettle guise.

A much darker story, Kachi-kachi Yama (かちかち山 ‘Fire-Crackle Mountain’) also known as the the ‘Revenge of the Hare’ 兎の大手柄, features an unusually evil tanuki. During harvest time, an elderly farmer catches a troublesome tanuki eating the tasty scraps left out for his beloved pet hare. He strings him up to a tree and returns to the fields, planning to slaughter him that evening for tasty tanuki stew, good for curing his piles. Furious, the wily tanuki cajoles and tricks the farmer’s kindly wife into untying his ropes. Once freed, however, he kills her and make a soup out of her thin flesh and brittle bones. As dusk falls, he then transforms into her likeness and waits.

When the hungry farmer returns, the tanuki serves his wife-soup to him, only telling him the horror of its ingredients after his belly is full. In his giddy triumph, the tanuki had completely forgotten about the farmer’s hare, however, who adored the dear old couple. Using the well-worn tricks of a tanuki against him, the hare exacts a slow and satisfying revenge, culminating in a thrilling boat contest. The hare hoodwinks the tanuki into building his boat from heavy clay, and in the middle of their race across a wide lake, it sinks like a stone, with the tanuki drowning deep in its muddy, weedy kappa-filled depths.

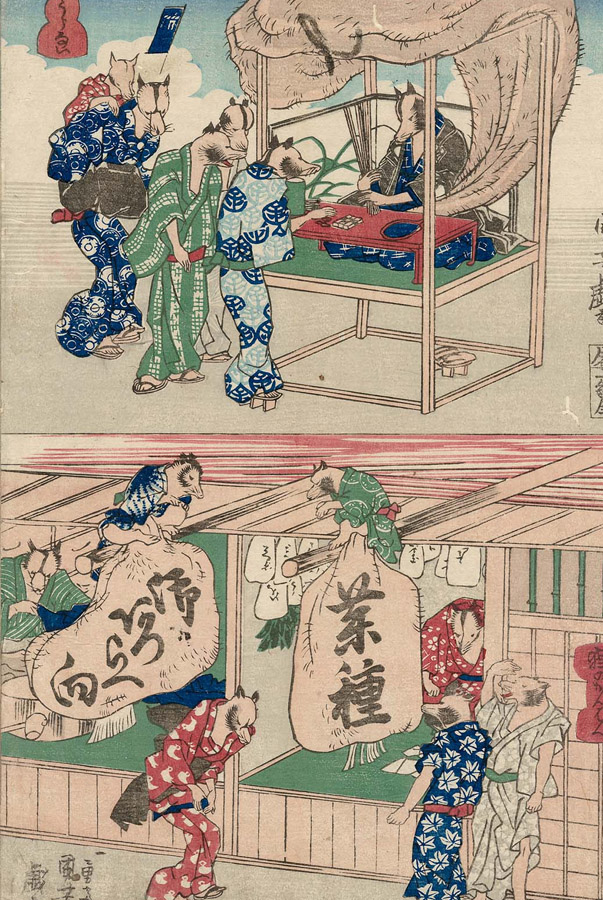

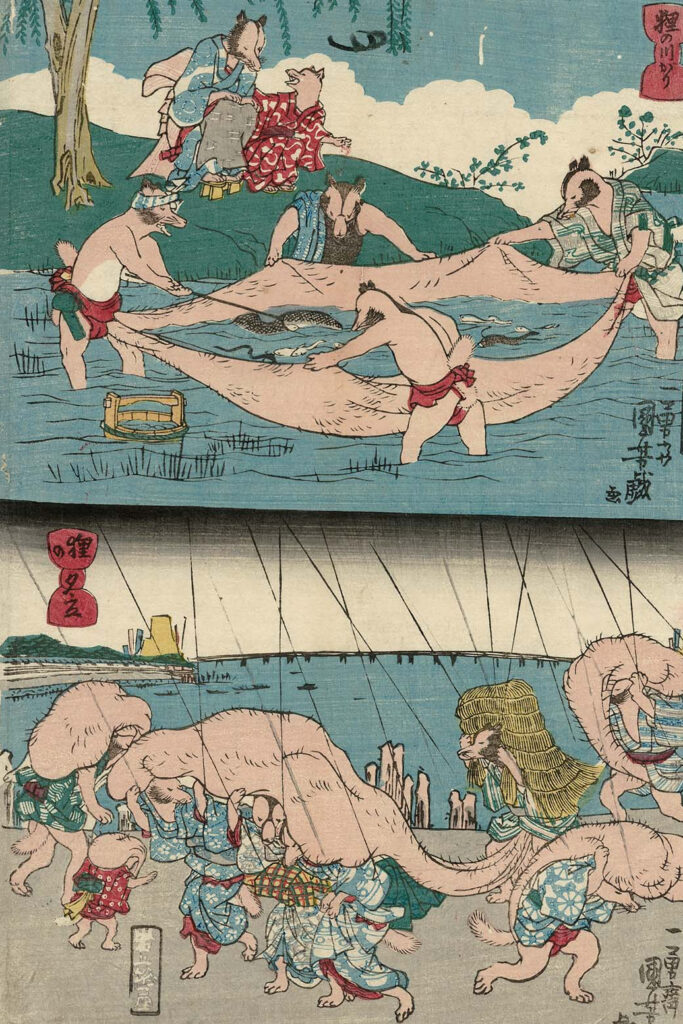

As the popularity of tanuki folklore and tall tales grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, images of their transformations, chicanery and foibles burst across the visual arts. In 1842, the eccentric ukiyo-e print designer, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, produced a series of comic tanuki prints, focusing on one of their defining attributes in the popular imagination – their gigantic, stretchable scrotums.

Known colloquially as kinbukuro (金袋, money bags), the tanuki scrotum was a symbol of good luck and wealth, rather than sexual potency. This seemingly odd association with money had a tangible historical basis, linked to goldsmiths in the artisan city of Kanazawa, who once used tanuki hides in the process of creating thin sheets of gold leaf. Tanuki skin was so rugged that by wrapping it around the malleable gold, even a tiny piece, it was said, could be then hammered out into the size of eight tatami mats (12 m2).[10] The phrase used for a small nugget of gold, ‘kin no tama’, was a homophone for the slang for testicles, ‘kintama’, and so, following the twists of language and art and myth, the tanuki became inextricably associated with an enormous scrotum, which in turn became synonymous with stretching your money and, by extension, affluence.

Kuniyoshi’s series of prints depicts these miraculous scrotums in a myriad of wild and wonderful ways. Tanuki use them to pound sweet mochi (rice cakes) and heat dashi (soup stock), as powerful fans, New Year drums, enticing shop signs, weights, carts and sacks, as a sturdy towboat to cross a swift-flowing river, as broad nets to catch wild birds and fish, as a fortune-telling tent, and as props to disguise themselves as yōkai (supernatural creatures) and kami (gods).

As the years slipped by and the race to modernise increased to a frantic pace, particularly after the seismic shifts of the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the magical, shape-shifting trickster of folklore and floating world prints began to seem uncomfortably out of place. Artists began to depict tanuki as representative of old fashioned, corrupt behaviour, of a Japan that was being cleansed by the newly enlightened Meiji society. The poor old tanuki tried to keep pace, transforming into steam trains and gas lighting, but it was too late and just as the Tôô Nippô news story recounted, they were literally and figuratively mown down by the relentless forces of modernity, by a brave new world of telephones and top hats.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, the tanuki’s subversive and sometimes frightening magic had been almost completely sanitized in the popular imagination. It became a comic and cuddly figure, bestowing good luck and financial prosperity in equal measure. In modern Japan, thousands of statues of wide-eyed tanuki – sedge hats perched at an angle, sake flask in one paw, a never-paid promissory note for the tab in the other – stand outside restaurants and bars, the last vestiges of their power enticing patrons to spend lavishly.

These iconic statues with their rigid, unchanging iconography, are typically Shigaraki-yaki, a type of ceramics produced in Shiga prefecture, in the west of Japan. They were first made in the late 1930s by the potter Tetsuzo Fujiwara (1876-1966), who dedicated his life to the production of tanuki statues after, it was said, as a child he saw a tanuki drumming its belly in the woods one moonlit night. In 1951, to welcome Emperor Hirohito on his visit to Shigaraki, part of his post-war national tour, the townsfolk lined up an eager row of tanuki figures each holding a patriotic flag. Hirohito was profoundly and unexpectedly moved and immediately penned a sentimental waka poem. The statues reminded him, he wrote, of his own beloved collection of tanuki dolls from his distant childhood. A faint symbolic touch of wildness and disorder in his pampered, rigid early years in the Aoyama Palace.

And this deep nostalgia for an idyllic, rural past, for the lost world of childhood, for the mountain mists and drifting wood smoke of a Japan where nature and humanity are as one, still flickers around the generic, disempowered figure of the tanuki, forever waiting for customers outside the brightly-lit doorways of provincial izakaya.

In Takahata Isao’s 1994 animated film, Heisei tanuki gassen pompoko (Tanuki Battle of the Heisei Era), set in the 1960s, a band of tanuki unsuccessfully attempt to halt the construction of a sprawling housing development in their idyllic home in the Tama Hills, just outside Tokyo. After numerous failed acts of resistance, including staging a ghostly yōkai parade to convince the human settlers that the land is haunted, the tanuki try one last desperate illusion: they briefly transform the landscape back to the shimmering, bucolic beauty of its pre-urban state.

But it’s too late. Bone-weary and resigned to the fate of their land, some of the tanuki blend into suburban society, shape-shifting into salary men and housewives and young couples, others begin to scratch out a place amidst the urban sprawl and golf courses. Funny and melancholy, the film’s arc stretches directly back to the beleaguered tanuki of the late 19th century, the same fight for the deep forest, the same powerlessness in the face of unremitting progress, and its inevitable concomitant of environmental destruction and displacement.

A couple of years ago, on a farm in Nanbu, Tottori Prefecture, an all white tanuki was captured sheltering from a typhoon in a cow shed by a farmer, Shunji Okuyama. Considered to be immensely lucky, it became headline news: a symbol not simply of a nostalgia for the old inaka, but of hope for the future. And faced with our current equally unstoppable train of climate change, species extinction, biodiversity loss, deforestation, water pollution and nuclear fragility, we desperately need the tanuki belly-drums to sound out in protest from the woods and fields of the satoyama, the place where humanity and wilderness intersect, and for their subversive and Rabelaisian magic to flare once more on the edges of our troubled, anthropocentric world.[11]

References & Further Reading

Michael Bathgate. The Fox’s Craft in Japanese Religion and Folklore: Shapeshifters , Transformations, and Duplicities. New York and London: Routledge, 2004.

A. Casal. “The Goblin Fox and Badger and Other Witch Animals of Japan,” Folklore Studies, vol. 18, 1959.

W. De Visser. “The Fox and Badger in Japanese Folklore,” Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, vol. 36, no. 1, 1908.

Steven J. Ericson. The Sound of the Whistle: Railroads and the State in Meiji Japan. Cambridge: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University and Harvard University Press, 1996.

Michael Dylan Foster. “Haunting Modernity: Tanuki, Trains, and Transformation in Japan,” Asian Ethnology, vol. 71, no. 1, 2012.

Violet H. Harada. “The Badger in Japanese Folklore,” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 35, no. 1, 1976.

Yumoto Kōichi, Zusetsu Edo Tōkyō Kaii Hyaku Monogatari 図説江戸東京怪異百物語 [100 Strange Tales of Edo Tokyo], Kawade Shobō Shinsha, 2007.

Melek Ortabasi. “(Re)Animating Folklore: Raccoon Dogs, Foxes, and Other Supernatural Japanese Citizens in Takahata Isao’s Heisei Tanuki Gassen Pompoko,” Marvels & Tales, vol. 27, no. 2, 2013.

Mark Schumacher’s tanuki page on his Japanese Buddhist and Shinto iconography website is also an invaluable resource.

[1] Okegawa was famous for fields of golden benibana (safflowers) and steamy thermal baths which were said to ease a number of persistent skin diseases.

[2] Reproduced in Michael Dylan Foster, “Haunting Modernity: Tanuki, Trains, and Transformation in Japan,” Asian Ethnology, vol. 71, no. 1, 2012, pp. 3-29. Foster’s article is a superb analysis of the clash of modernity and tradition represented in the tanuki train stories. See also, Steven J. Ericson. The Sound of the Whistle: Railroads and the State in Meiji Japan. Cambridge: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University and Harvard University Press, 1996.

[3] With the classification of Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus (literally, “civit-like night wanderer”).

[4] Haruo Shirane, Japan and the Culture of the Four Seasons: Nature, Literature, and the Arts, Columbia University Press, 2013.

[5] The Zokutō Ritsu or Penal Laws for Theft (賊盗律) also banned any making of magical inscriptions or spells. See Herman Ooms, Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: The Tenmu Dynasty, 650-800. University of Hawaii Press, 2008.

[6] This story appears in similar form in the Konjaku monogatari shū (Tales of Times Now Past, twelfth century) and Uji shūi monogatari (A Collection of Tales from Uji, thirteenth century), both collections of setsuwa, short miscellaneous tales. For English translations, see, for example, D. E. Mills, A Collection of Tales from Uji: A Study and Translation of Uji shûi monogatari. Cambridge University Press, 1970.

[7] Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, Yokai Attack!: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide. Tuttle Shokai, 2012.

[8] The sound of drumming was known as Tanuki Bayashi 狸囃子, literally ’tanuki accompaniment’.

[9] There are excellent English translations by Zach Davisson of many of the tales from this collection, including this one, which mine is based on, at hyakumonogatari.com. Yumoto Kōichi, Zusetsu Edo Tōkyō Kaii Hyaku Monogatari 図説江戸東京怪異百物語. [One Hundred Strange Tales of Edo Tokyo], Kawade Shobō Shinsha, 2007.

[10] This connection was traced by Ōwaku Shigeo 大和久重雄 in his book Hagane no Chishiki 鋼の知識 [Knowledge about Steel]. Diamond Shakan, 1971. See also Alice Gordenker, “Tanuki Genitals,” Japan Times, July 15, 2008.

[11] “Rare white raccoon dog caught,” Japan Times, October 18, 2013.