“The ground was rising steadily, and as they went forward it seemed that the trees became taller, darker, and thicker. There was no sound, except an occasional drip of moisture falling through the still leaves. For the moment there was no whispering or movement among the branches; but they all got an uncomfortable feeling that they were being watched with disapproval, deepening to dislike and even enmity. The feeling steadily grew, until they found themselves looking up quickly, or glancing back over their shoulders, as if they expected a sudden blow.”

– J.R.R. Tolkien FOTR. Ch. 6

Tolkien describes the Old Forest, a space filled with deep-rooted mysteries and danger in Middle-earth. Although, this takes place in his “secondary world”, it still sets the mood, turns our thoughts in the right direction, as we try to imagine the deep, dark and mysterious forests of the Nordic countries, which are very real and exist in our world. Imagine that the power within the forest realm, the one that is watching every step you take, is in fact the ruler of the forest; a spirit that takes the form of a lovely young maiden who seduces or lures wanderers astray deep in the forest realm? This strikingly beautiful, but highly treacherous female forest spirit is known from thousands of folklore records, predominantly from Sweden, but comparable to related supernatural beings in Finnish, Norwegian and in Danish folklore. In the following, I will give some basic description of this kind of forest spirit, mainly from Swedish folklore, but with some comparisons from other Nordic countries.

Perilous forest realms

Dealings with supernatural forest spirits are old and belong to a popular tradition of pre-Christian origin in Scandinavia. It goes back at least to the Viking Age. In the Poetic Edda, we hear of a troll woman that sits in the Iron Forest, giving birth to all the wolves in the world. Other supernatural creatures haunt the forests in the Old Norse sources – trolls, giants, witches, werewolves and other shapeshifters, dangerous beasts and other horrors. In Old Norse, some words for outlaws designate their association with the forest and wild nature such as skógarmaðr ‘forest man’ or skóggangsmaðr ‘the one who walks in the forest’. We can be certain that, since an early age, the forests have been associated with menacing and dangerous forces, both of a natural and of a supernatural kind.

In contemporary times, forests cover vast areas in the Nordic countries: roughly 75% of Finland, almost 70% of Sweden, more than 30 % of Norway, and 15 % of Denmark (even Iceland had some forests before the colonisation by the Norsemen). With this in mind, it might not come as a surprise that narratives about – and a belief in – a forest spirit was particularly strong in Sweden and Finland. Today, we Scandinavians might have romantic notions about the forest as a place for berry and mushroom picking, or the forest as a space for hiking, leisurely walks and spiritual healing. For some it is a place for hunting as a hobby or as a place for work. However, no one goes there without technical aids such as a mobile device with a GPS or a compass.

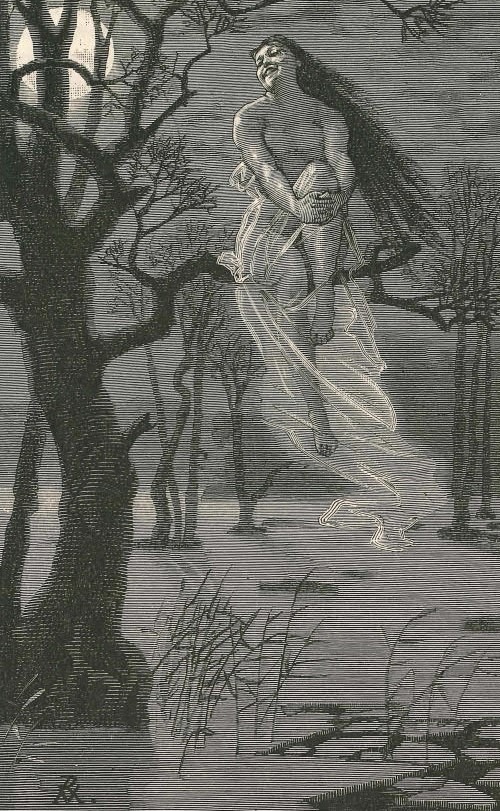

This was hardly the case in earlier days. Then it was a haunted place full of marvels and perils, an otherworld full of potential violence and dread, a site of exclusion and a refuge for outcasts and bandits as well as for supernatural beings. The forest was undeniably a dangerous and perilous space. Small changes in the weather or a simple mistake could lead to misdirection and make a person wander in the wrong direction or in big circles. There was always a risk of getting lost, of encountering predators such as wolves or bears, and in the worst-case scenario, even perish within the forest. People did not venture into the forest of their own free will for a longer period without good reasons. Those who did risked never coming back again.

What to call the foxy forest spirit…

There are different stories of a wild, untamed forest space ruled over by a supernatural owner of nature, its Genii Loci. The forest spirit have many different names. In Sweden she is known as skogsrå, skogsrådan, skogsråa ‘forest ruler’, råan, rådande ‘the ruler, the ruling spirit’, skogsjungfru ‘forest maiden’, skogsfru, skogssnuva ‘forest woman’, skogskäringen ‘the forest hag’, or with a nickname such as Grankotte–Maja ‘Spruce cone-Maja’, Talle-Maja ‘Pine tree-Maja’. She can also be called by a name that is local and not known outside a certain area such as Gonna, Besta, Rånda, Skogela, Lanna-frökna ‘The lady of Lanna’ or Ysäters-Kajsa ‘Kajsa of Ysäter’. On the island of Gotland, there are records of a female troll known as Torspjäska that plays the same role and has the same function as forest spirit on the mainland.

In Norway, the word huldrefolk or huldre (plural) derived from Old Norse huldr ‘hidden’ is used for all kinds of supernatural beings, sighted and talked about by the folk. Hulder, or Huldra in the singular, signifies a female forest spirit, even though she might as well appear in mountains. This is the same line of thinking that we find in Swedish folk tradition, were the forest spirit act and appear alone, not a part of a collective or families of supernatural beings, like vittra. In northern Sweden, the name vittra refers to a group of supernatural beings that lives underground that have many traits in common with fairies from folklore of the British Isles, as well as with the ellefolk in Danish tradition or the huldrefolk in Norwegian tradition. These beings could also appear solitarily and seduce humans, spirit them away into their dwellings or even steal and exchange babies with their own. For example, in Sweden, a solitary female vittra was a vitterkvinna; in Denmark, a solitary female from the ellefolk was an ellepige or ellekvinde. It seems as if many narratives about nature spirits once seems to have had much in common, from their seductive roles to the belief in their ability to give or take luck in hunting, fishing and so on, and them herding cattle and living a kind of parallel life to that of mankind.

In Finland, many of the words are similar to the ones used in Sweden, which is natural considering that Swedish was the major language in Swedish Finland. Some names in the Finnish language, mainly from the west coast, also show a link to the Swedish traditions, for example, metsänpiika ‘forest girl’ or metsänneito ‘forest maid’ are the most widespread words used in Finland for the female forest spirit. However, there are also other localised names such as haapaneitsyt ‘aspen-maid’ or sinipiika ‘blue maid’. In Finnish tradition, the haltia/haltijas ‘supernatural being(s)’ of the forest was usually male, ruled over by Tapio, the king and ruler of the forest. In Finnish, it is also common to speak of väki, a word denoting ‘the strength, the power’ of something, for example of the forest.

In Central Europe, corresponding fictional characters are for example the female, beautiful, longhaired tree maiden known in German folklore as Holzfräulein ‘the tree lady’, who was dressed in leaves, or as Moosweiblein ‘the moss woman’. Groups of supernatural and dangerous forest women also appear in the Baltic countries, for example in Estonian folklore. Otherwise, in European folklore, it seems to be far more common with a male forest spirit or a spirit linked to vegetation and spring, for example Tapio in Finnish folklore or even (this might be a stretch) the Green Man in English folklore. In many cultures, a common notion is that the forest is the haunt of different spirits and supernatural denizens, but also that the forest by itself could act as an active supernatural agent.

The seductress with many guises

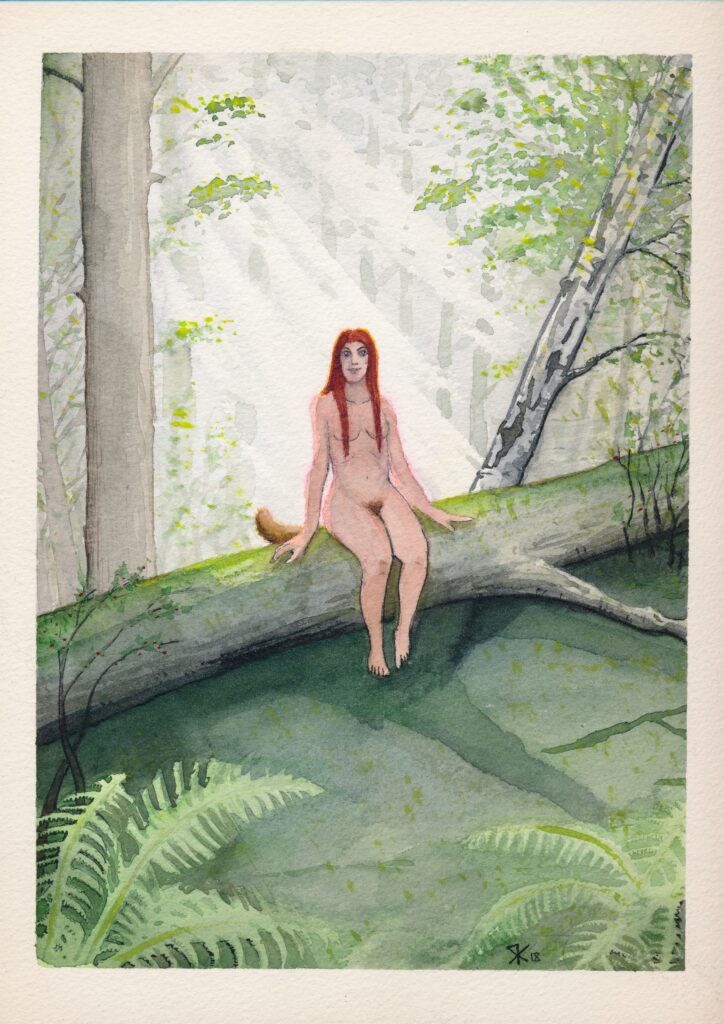

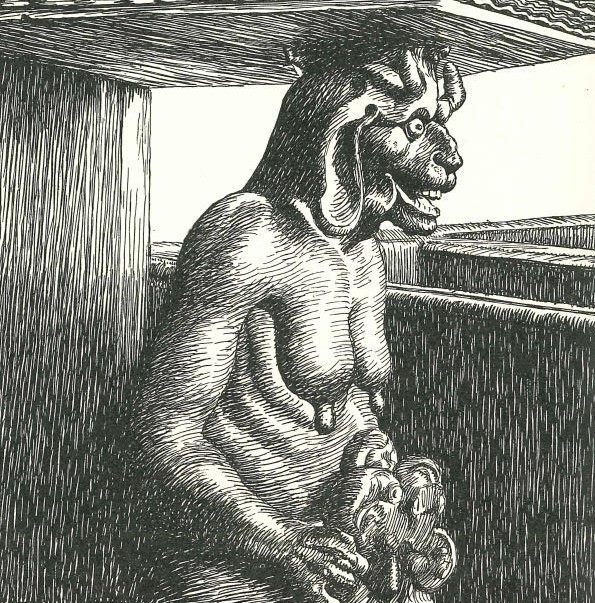

Many of the stories concerning an encounter with a forest spirit is of an intimate nature, referring to men having a sexual relationship with her. She is a physical being, made up of flesh and blood and can, at least in some folk legends even become pregnant and deliver the child to the unsuspecting father. In Sweden, and Norway (and Swedish Finland), the forest spirit is female, frequently described as looking like a beautiful woman from the front, but with a backside like a rotten tree trunk. Another motif is that she has a cow tail and sometimes hooves and/or furry legs. The descriptions are indicative of her liminality as someone who partly belong to the wild nature and its beasts. The best way to describe her would be as an anthropomorphic personification of the power of the forest realm. Male forest sprits are rare in Swedish folklore, but not unheard of. Sometimes they act as the female forest spirit’s husband.

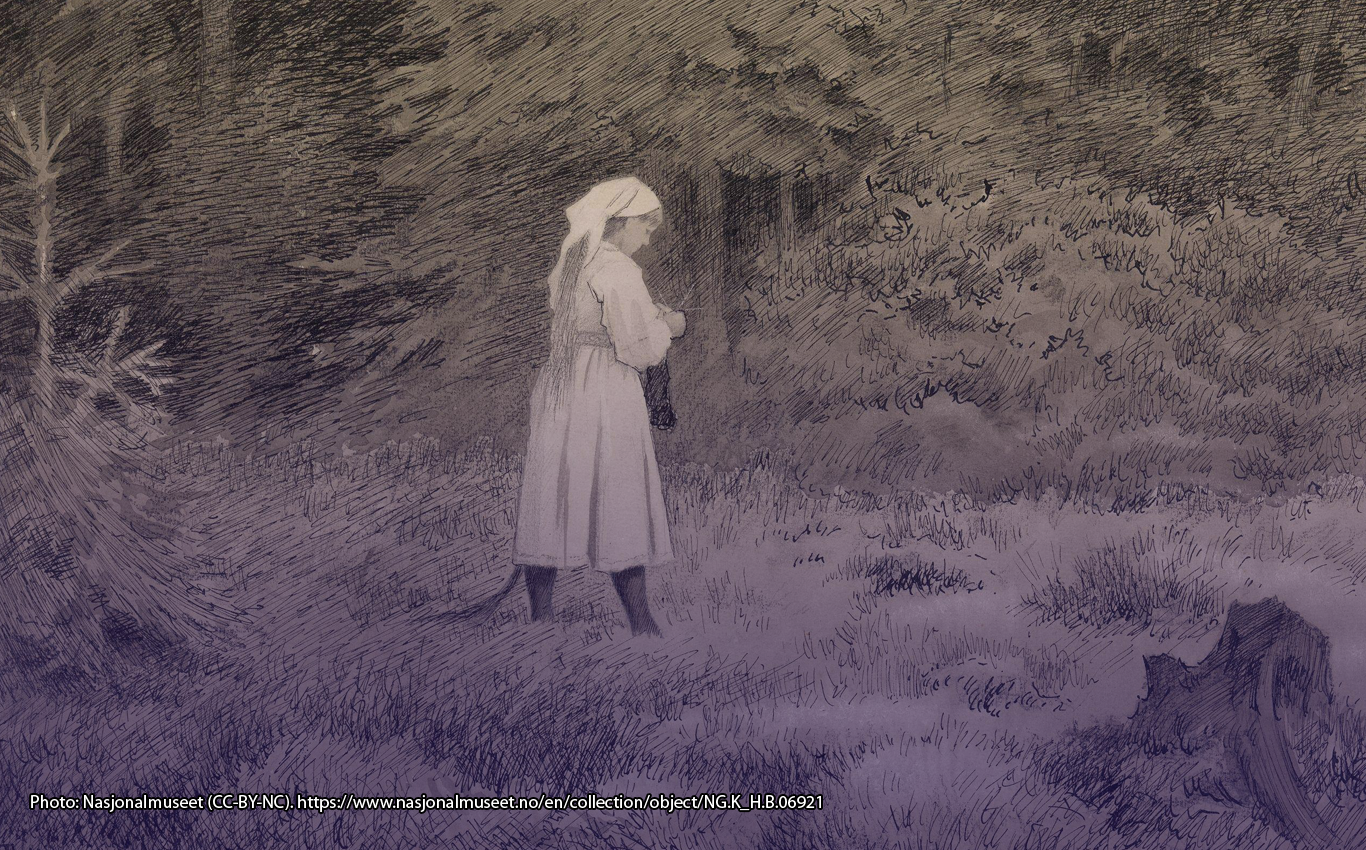

Even if most people probably imagine Scandinavian nature spirits as young and attractive naked anthropomorphic beings, this is not always consistent with tradition. Many artists during the 19th century used nakedness as a motif in their paintings, especially in combination with romantic portrayals of nature. In the records of the folklore archives, many accounts speak of beings such as the water spirit (linked to streams, waterfalls and rivers) or the female forest spirit appearing fully dressed, and with quite fancy clothes at that. One thing is that she could – like most supernatural beings – shapeshift and transform into an animal or an object, grow in height so that she became as tall as the treetops, or distort the vision and cause illusions for those who ventured into the forest.

Descriptions vary, as might be expected when it comes to supernatural beings. Generally, the forest spirit is described as looking like a human being, but with something that makes her stand out, she can be exceptionally beautiful from the front but have a tail or a back formed like a (rotten) tree trunk. The first type is common in Denmark, mid- and southern Sweden, as well as Swedish Finland, the latter is more common in western and northern Sweden and Norway. Normally, the tail is a cow’s tail, but there are also descriptions mentioning that she had a horsetail or a foxtail, or that just say that she has a tail or a ‘rump’. Generally, the narratives speak of the forest spirit as an attractive young woman but some legends paints a different picture and describes her as old and ugly, a hag of the forest. When she is young and attractive, her erotic and seductive traits are apparent when she is naked, with only her long hair covering parts of her body. Sometimes she is brushing her long hair when she show herself in the forest. In the following Swedish account from 1927, August Andersson, born in 1858 in Västergötland, relates a rather typical description of the forest spirit:

There was an old woman, Kajsa, who would have been 140 years old today, if she would still be alive. She served in Längum, and she said that there they had big open spaces where they released their animals. At one time, one of the men went looking for the horses. He searched far and wide, but could not find them. After a while, he ended up in the end of Galgeberg in Främmesta, and there stood a grand woman, combing her hair, but her back was hollow and looked like a kneading trough. She told him, where the horses had gone. That was a skogsrå (IFGH 1143, p. 3).

Some records mention that the forest spirit has long breasts. A common motif in some legends is that she could throw her breast over her shoulders, something she did when she was running from something, for example, the leader of the Wild hunt (a king, a hunter, Thor or Odin). Speaking of the Wild hunt, one of the hunted supernatural female beings in Danish folklore is Slattenlangpatte, a name that translated as ‘flabby long breasts’. She is a wicked being, a troll woman that devours humans, but is also one of the ellefolk, an ellekvinde, and as such related to the forest spirit in other parts of Scandinavia. As mentioned earlier, not all of the descriptions of the forest spirit portrays her as a beautiful and attractive young woman, some describe her as a beast or a hybrid between a human and an animal.

A folk legend, collected in 1935 by the schoolteacher Fosse in Sogn (western Norway), speaks of an encounter with a huldra. The description is typical of these kind of narratives:

A grown lad from Systrand spent a winter snaring grouse up at a seter in the parish. He had a dog with him. One evening, as he was sitting by the hearth cooking his food, he heard something rattling outside against the wall. The seter was made of stone and had a turf roof. Shortly after, someone came in the entryway and knocked at the door. The dog barked and its hair stood on end, and then in came a beautiful maiden. The boy had never seen so beautiful a maiden before. She was wearing a red bodice and a blue skirt, and she had long, fair hair which hung down her back. The boy was quite amazed that a girl would come to the seter in the middle of the winter. It was seven miles to the town, and the snow was deep. She started talking to him and asked if he did not think it was lonely to stay up at the seter in the middle of the winter. She laughed and talked, turning and twisting, and showing off to him. He answered back, laughing and joking, and thought this was really fine. At last he asked if she would stay there. Then it would not be so lonely any more. A strange expression came over her face, and she turned away from him, and then the boy saw that she had a long tail which hung below her skirt. Now he understood that she was a holder and that she wanted to marry him. He had heard that huldre-folk liked to marry Christians (Christiansen 1964, p. 128–129).

The boy sneaks outside with his dog, and escapes with her unnaturally fast skis made of brass, but she chases him on his skis, catches up with his dog, and breaks its back with the ski pole. The boy made it back in one piece and the narrator claims that the huldra’s brass skis are still supposed to be at the farmstead.

Making love

The crown and the church viewed intimate relationships with the forest spirit as a crime that could lead to catastrophic consequences. Men accused for having sexual relations with the forest spirit, and women for having sexual relations with the water spirit (the neck), turns up several times in judicial records from the 1600s and 1700s in Sweden. The trial records show that people could be (and actually were) sentenced to death for this crime. This subject has been the subject of an article by Jonas Liliequist (2006) and in depth in a PhD dissertation by Mikael Häll (2013).

It is a significant example of a clash between different worldviews, the folk versus the elite. According to a common belief, the forest spirit approached men who were alone in, or close to, the forest. In the folklore material, two groups stand out most regularly for encounters with the forest spirit – the charcoal-burners on the one hand and the hunters on the other. That is, men who are alone in the forest for long periods at a time. Not all stories speak of the encounters as negative. When the man was willing and actually became the forest spirits lover, she could help him and grant rewards, from blowing in his rifle barrel so that it never missed, to helping him in times of crisis, for example waking him up if the charcoal stack was about to burn down.

When it comes to sexual activities, the female forest spirit plays the active part. She approaches and tries to seduce the man by different means. If all else fails, she pulls up her skirt and shows her private parts (like most women in preindustrial rural Scandinavia, she wore no underwear), in an attempt to have intercourse with him. One account collected in Sweden from Östergötland in 1928, speaks of such a meeting:

Our informant [a farmer, born 1900] said that he met the forest maiden on a forest trail, between Stensjön and Järkerhult in Blåvik. This happened in autumn around nine o’clock in the evening. She came to him and spluttered something. She came up close to him, rolled up her skirt and was naughty. The informant backed away but she followed him for a bit. After that, he never saw her again. She was dressed in an old-fashioned black dress (ULMA 1847:3, p. 5)

Not every attempt at seduction succeeds as the quoted legend shows. A common version of how the forest spirit fails or the man outwit her is a legend type known as “Self burnt me”. The legend usually plays out in the following manner: a man is sitting by his campfire when the forest spirit approaches. She asks for his name and he answers “Self”. The forest spirit sits down close to the man, tries in vain to seduce him, and eventually exposes herself. He takes a firebrand (or throws boiling water) and burns her private parts. The forest spirit runs away screaming, “Self burnt me!” A male voice from the forest answers, that she has herself to blame. The motif is old, known in another context in the Odyssey when Odysseus outwits the cyclops Polyphemos.

The most common erotic encounters takes place in the charcoal stacks (kilns) or by a campfire in the woods. According to many folk legends, a man gets a reward for having intercourse with her and a common legend type relates how a man spends the night in a forest cabin. During the night, she visits him and they have intercourse. She thanks him by letting him shoot an elk or a bear during the next morning (usually, by showing him where the animal sleeps or rests). The same type of legend also has a negative outcome if the man refuses to have intercourse with her. Then she makes sure that he will get bad hunting luck. Other legends speak of a man who finds a house or a bed in the forest and that he meets and have intercourse with the forest spirit there. When he wakes up, he finds himself hugging a tree or even finds himself in a marsh (the latter is usually the result of him saying his prayers before lying down in the bed). According to another legend type, the forest spirit was able to take the shape of the man’s wife and come to him with food in his charcoal kiln. After having intercourse with her, he later meets his real wife and realizes that the first woman was the forest spirit. It might not come as a surprise that most scholars have interpreted these legends as erotic fantasies emanating from lonely men thinking about women and sexual activities when alone in the woods.

Legend types associated with the forest spirit

There are many different beliefs and narratives about the forest spirit, too many to mention here. In my article, “Spirited Away by the Female Forest Spirit in Swedish Folk Belief”, recently published in Folklore (Vol 131:2), I look at belief in the forest spirit as the cause for people being spirited away or getting lost in forests. Furthermore, the article compares the belief in a female forest spirit as the active agent in Swedish folklore to the concept of the Finnish term metsänpeitto ‘forest cover’, in Finnish folklore, where the forest itself is the active agent. Legends reinforce the danger of getting lost in a forest, especially in dense forests like those found in Sweden and Finland.

A common belief found in different types of narratives is that the forest spirit was able to lead people astray and this is something that could happen to everyone who had business in the woods, even experienced hunters. She could change the environment, hide trails, and create deceptions. When she had led someone astray, the person who was lost in this way could hear a shrill laughter – a sure sign that it was her doing. The forest spirit was the ruler of the forest realm, she was its sovereign ruler of all that was in the forest, including over its animals. This makes her the dominant force in the forest and earns the respect of hunters, for if she was angered or for some reason was annoyed at the hunter, she could make sure that all the game of the forest became invulnerable from gunshots and traps, or she could hide all the animals from the hunter in question.

In Sweden, many of the legend types have been collected by Bengt af Klintberg in his The Types of the Swedish Folk Legend (2010); they are collected under the heading “E. Spirits of the forests”. Although most narratives describe the forest spirit as dangerous – she did belong to the dangerous otherworld after all – not all encounters are bad or dangerous. Like most supernatural beings in Scandinavian and Nordic folklore, she could reward someone who treated her well or showed her good manners and respect. The following Swedish narrative, written down in 1930, describes a common motif associated with the forest spirit told by a man born in 1851 in Värmland:

I heard my mother say that once at a market a man among the crowd discovered skogsrån. A farmhand saw her and noticed that she had a tail and said: “Miss, would you mind pulling in the train (of your dress)?” She thanked him for this and asked him to look at the shelf in the stall the next morning; there he would find a reward. He did so and found a piece of gold (IFGH 2045:17).

Supernatural beings are a part of our world; they are old and as ancient as nature itself. However, according to many folk legends, the supernatural nature spirits were the fallen angels expelled from heaven together with Lucifer, condemned to remain on earth and ruling over the place where they once fell. On the other hand, no single explanation is enough to explain or classify supernatural nature spirits. The forest spirit represents wild nature, as a counter-image to cultural order. She roams the in the vast and deep forests of Scandinavia and Finland. So, if you find yourself face to face with a beautiful maiden of the forest, be polite and treat her with respect. Otherwise, you might never leave the woods again.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Literature

Bø, Olav. Trollmakter og godvette. Overnaturlege vesen i norsk folketru. Det norske samlaget: Oslo 1987.

Christiansen Reidar (ed.), Folktales of Norway. Translated by Pat Shaw Iversen. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago & London 1964.

Granberg, Gunnar. Skogsrået i yngre nordisk folktradition. Lundequistiska: Uppsala 1935.

Hodne, Ødne. Vetter og skrømt i norsk folketro. J. W. Cappelens Forlag: Gjøvik 2002.

IFGH = The Institute for Language and Folklore, Gothenburg.

Häll, Mikael. Skogsrået, näcken och Djävulen. Erotiska naturväsen och demonisk sexualitet i 1600- och 1700-talens Sverige. Malört: Stockholm 2013.

Klintberg, Bengt af. The Types of the Swedish Folk Legend. Academia Scientarum Fennica: Helsinki 2010.

Kuusela, Tommy. “Då gick ett rå genom skogen”. Föreställningar om skogsrå i Gästrikland. In Från Gästrikland 2018: Folkbildning och folktro. Gästriklands kulturhistoriska förening: Gävle 2018: 40–65.

Kuusela, Tommy. Spirited Away by the Female Forest Spirit in Swedish Folk Belief, In: Folklore Vol. 131 No. 2, 2020: 159–179.

Liliequist, Jonas. ”Sexual encounters with spirits and demons in early modern Sweden: popular and learned concepts in conflict and interaction”. In Christian Demonology and Popular Mythology, edited by Gábor Klancizay and Éva Pócs (Demons, Spirits, Witches Vol. II). Central European Press: Budapest & New York 2006, 152–169.

Olrik, Axel & Hans Ellekilde. Nordens gudeverden. Köpenhamn: Gad 1926-1951.

Sarmela, Matti. Finnish Folklore Atlas. Ethnic Culture of Finland. 4th partially revised edition, translated by Annira Silver. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society 2009.

ULMA = The Institute for Language and Folklore, Uppsala.