Being an island nation, it goes without saying that the ocean has a strong influence on Japanese folklore and culture. In Mie Prefecture, on the south-east coast of Honshu, it is inescapable. Mie’s Shima Peninsula is a place where salty wind leaves your hair in constant tangles, the air perpetually smells of fish and sun-dried seaweed, and fragments of seashells crunch beneath your shoes and the tyres of your car. It is also home to the ama divers, an ancient tradition of women who breath-dive for abalone, and Ise Jingu, the most sacred Shinto shrine in the whole of Japan. Over three days, I explored the rugged coastlines of Ise-Shima to learn about ama culture and Japanese ocean folklore firsthand.

The Ama Divers

Ama divers are an ancient part of the Shima Peninsula, with archeological evidence of their existence dating back at least 3,000 years. They are all female, and they use no equipment to dive. Instead, they use a special breathing technique called isobue (ocean whistle) to prepare for holding their breath underwater. The average length of an ama dive is fifty seconds, known as a ‘fifty-second battle.’ There are two types of ama divers: kachido ama, who swim from the shore to shallow diving sites, and funado ama, who travel in boats to deeper diving sites.

The owner of the guest house I stayed in was extremely kind, and keen to support my interest in the ama. Early one morning, he drove my friend & I out to a small harbour in the hopes that we could see some ama at work – and we were in luck! We walked along the sea wall, watching kachido ama and skirting around amagoya, the huts where ama divers store their belongings and socialise after diving. We also saw boats of funado ama return, and tip-toed our way along the docks to watch them unload and hang up the seaweed they had caught. It’s easy to relegate ancient traditions to the past, but being there and seeing the ama, seeing their clothes and shoes discarded on the shore, and chatting to their families who arrived to help them bring in their catch, reminded to me that they are real people who belong to a still thriving community. Culture and folklore are not always things to be merely read about, and having the privilege to get involved with them in person is a profound, enlightening experience.

Ise Jingu

Ama harvest a variety of things including sea cucumbers, seaweed, and sea snails. But the abalone which they catch in the summer is the most significant. Aside from being a valuable source of food and profit, abalone also have a spiritual connection with Ise Jingu. It is believed that eating abalone contributes to longevity and youth, and therefore the deities favour them. Three times a year, ama give food offerings called shinsen to Ise Jingu. These shinsen are composed of noshiawabi, which are dried strips of abalone meat held together with straw. The abalone for the shinsen are caught as part of Shinto rituals to pray for a safe and abundant diving season. The largest of these rituals is called Mikazuki Shinji, and takes place in the town of Kuzaki every June. Many local people volunteer to help make the noshiawabi at this time.

It is believed that Ise Jingu was established around 2,000 years ago by Yamatohime-no-Mikoto, the daughter of Emperor Suinin. She was tasked with finding a suitable place to hold ceremonies to worship Amaterasu, the Shinto goddess of the sun and the universe. Shinto has a lot of deities, but Amaterasu is one of the most important (because y’know, the sun and the universe are rather vital to life after all!) After many years of searching, Yamatohime-no-Mikoto arrived in Ise. She felt the presence of Amaterasu, who spoke to her and said she wanted to live forever in Ise near the mountains and the sea. Happy to oblige, Yamatohime-no-Mikoto established Naiku, the Inner Shrine of Ise Jingu, in that exact spot. Naiku is dedicated to Amaterasu, and she is believed to live there enshrined in her own special quarters. A short distance away is Geku, the Outer Shrine, which is dedicated to Toyouke, the god of agriculture. Every twenty years, the entirety of Ise Jingu is demolished and rebuilt as a homage to the Shinto beliefs in death, renewal, and the impermanence of life. Once it is rebuilt, special ceremonies are held to move Amaterasu and Toyouke into their new homes.

According to legend, after establishing Ise Jingu Yamatohime-no-Mikoto visited the Shima Peninsula and ate some abalone which was caught by an ama woman named Oben. Yamato-hime-no-Mikoto was so thrilled by the flavour of the abalone that she requested Oben provide offerings of them to Ise Jingu. Oben agreed, and ever since then that is what has been done.

The soft, guarding presence of Ise Jingu hangs over Mie. Forgetting the hundreds of subsidiary shrines dotted around and the rustic straw rope and shide adorning thresholds, the same calm energy I felt when visiting Ise Jingu seems to be everywhere. Whether you believe that Amaterasu lives there or not, it is undeniable that it holds some kind of otherworldly power.

Legends of the Sea

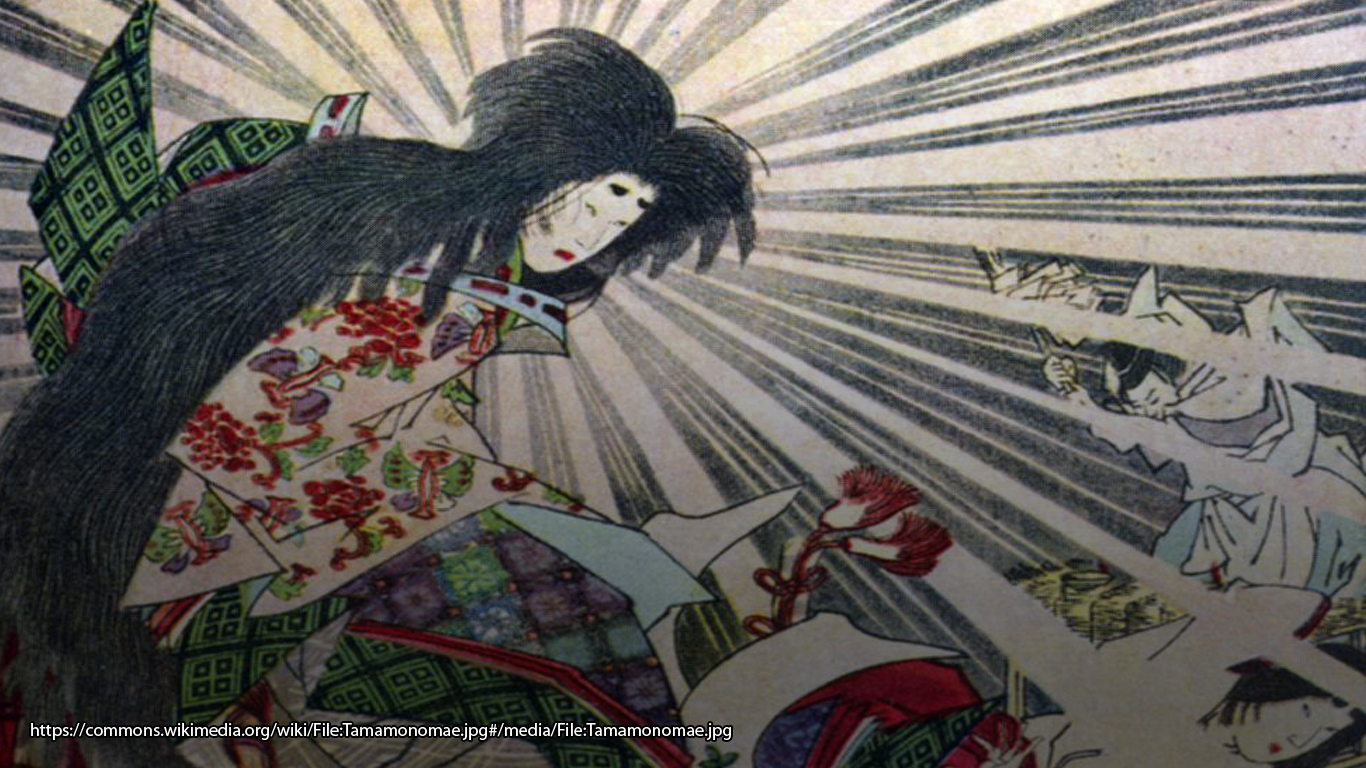

The ocean is a mysterious place, and there are many malevolent creatures said to lurk beneath the waves, ready to prey upon unsuspecting ama. One of the most feared is the tomokazuki. This sea demon takes on the appearance of an ama diver, and materialises before a real ama and attempts to lure them closer by offering abalone. If the ama accepts, the tomokazuki leads them deep into the ocean and drowns them. It is also believed by some that tomokazuki are the spirits of drowned ama. The other sea demon which is said to target ama is the shiri-koboshi, a monster which attacks its prey by pulling their insides out of their anus. Nasty!

To protect themselves from these supernatural evils, ama divers mark their diving clothes and tools with symbols called seiman and doman. Traditionally this was done with black sewing thread or purple shell dye, but the ama divers I saw had etched them onto their floats with what looked like black marker pen. Moving with the times! The seiman is a 5-pointed star drawn with a single stroke, so there are no gaps for evil to enter. The doman is a lattice made up of 5 horizontal lines and 4 vertical lines. The spaces between the lines represent many eyes watching out for evil, and the complex structure means there is no clear entrance for evil to get in. If an ama diver is seen in the ocean without the seiman and doman, then she is a tomokazuki.

As well as using the seiman and doman, ama women also perform a small protection ritual before diving. This involves filling their mouths with sea water and tapping the edge of their boat (funado ama) or the rim of their bucket (kachido ama) with their abalone chisels whilst chanting a ‘chu chu’ sound. This ritual is called ‘cried mice.’

The ocean is also home to benevolent creatures. Another folk tale tells of an ama who was invited to visit Ryugu-jo, the palace of the ocean Dragon King Ryujin. Whilst there, the ama was given a casket of treasure by Otohime (‘hime’ means ‘princess’ in Japanese, so Princess Oto). In Shinto, Ryujin is a god of the ocean revered for his wisdom. It is said that people who drown in the sea live on with him in Ryugu-jo.

Otohime also appears in the Japanese folk tale “Urashima Taro,” which is accredited as being the oldest story in the world involving time travel. Similar to the ama story, a man called Taro is invited to visit Ryugu-jo. He stays there for three days, and before returning to land he is given a magical box by Otohime. She tells him not to open it, but of course he does. At the surface, he discovers the real amount of time he spent beneath the sea was 300 years, so he is now in the future and his mother is gone. Grief-stricken, Taro opens the box. Instantly he transforms into an old man, because the box contained his old age.

One of my favourite Japanese words is inaka. In English, we might translate it as ‘rural’ or ‘countryside.’ But in Japanese, inaka encompasses so much more than that. As well as the landscape, inaka is the feeling of isolation and peace which comes with being off the beaten track. The inaka is where magic happens; where you can find hidden things, like tiny harbours and sea demons, and experience alternative ways of life. Folklore is not just about mythical creatures and stories, but also about people – it has the word ‘folk’ in it after all. It belongs to the communities who share and believe in it. In the wild beauty of the Ise-Shima inaka, folklore thrives. It is preserved in the rocks and the gates of seaside shrines; in the voices and woodsmoke drifting out of the amagoya.

After thousands of years, the wooden buildings of Ise Jingu still stand in the same place, and the ama women continue their fifty-second battles. So long as the waves keep striking the shores of the Shima Peninsula, neither will change.