Rather than romance, fairy tales often focus on relationships within families – interrogating the many ways in which these can break down, but also celebrating family members who love and assist one another. Sisters in particular play pivotal roles in many fairy tales: in this essay I look at a number of tales in which sisters and stepsisters rescue or redeem their siblings via the various strategies of self-sacrifice, wit, magic and bravery.

In 2013, Disney released the story of two princesses: Elsa, with power over ice and snow, and her young sister Anna. When Elsa accidentally strikes frost into her sister’s heart, the film plays on our expectation that a prince will save Anna. Instead, romance is sidelined and the spell is broken by sisterly love and courage. Hailed as a refreshing departure from the cliché of ‘fairy-tale romance’, the film was a huge success. The sequel will be out this year.

Yet Frozen is more traditional than you might think. Fairy tales are not terribly interested in romantic love – the marriage-at-the-end is usually a mere signifier of worldly success. They take far more of an interest in family dynamics, which they depict with unsentimental, even brutal realism. Mothers die; fathers are weak, unjust, even incestuous; stepmothers are cruel; stepsisters jealous. It’s family friction that often forces the heroine into the world. After a misunderstanding with her King Lear-like father, the heroine of ‘Cap o’ Rushes’ is thrown out to find work as a servant; her eventual marriage is less an end in itself than an opportunity to teach her father a lesson and enact a reconciliation.[1] Troubles (say fairy tales) begin at home.

As in real life, siblings in fairy tales sometimes get on and sometimes don’t, and in spite of their reputation, step-siblings are not always malevolent. Little Marlinchen of ‘The Juniper Tree’ loves her murdered stepbrother dearly,[2] and the two Kates of ‘Kate Crackernuts’ stick together, stepsisters though they be.[3] Many a fairy tale celebrates the love between siblings who remain faithful through thick and thin – and it’s notably sisters who rescue their brothers, not the other way around. A touching tenderness appears in many of these tales.

Little brother took his little sister by the hand and said, ‘Since our mother died we have had no happiness; our stepmother beats us every day… Come, we will go forth together into the wide world.’

They walked the whole day over meadows, fields and stony places, and when it rained the little sister said, ‘Heaven and our hearts are weeping together.’[4]

Yes, the little brother initiates the action, but within a few lines his sister is telling him repeatedly not to drink from the brooks their wicked stepmother has bewitched – for she, not he, can hear the warning voice of the water. When he fails to obey her and is changed into a deer and hunted, he becomes entirely dependent on his sister’s aid. In the same way, in spite of Hansel’s clever trick of dropping white pebbles to lead them home, it’s he who is shut in a cage and Gretel who saves his life, vigorously shoving the witch into her own oven.

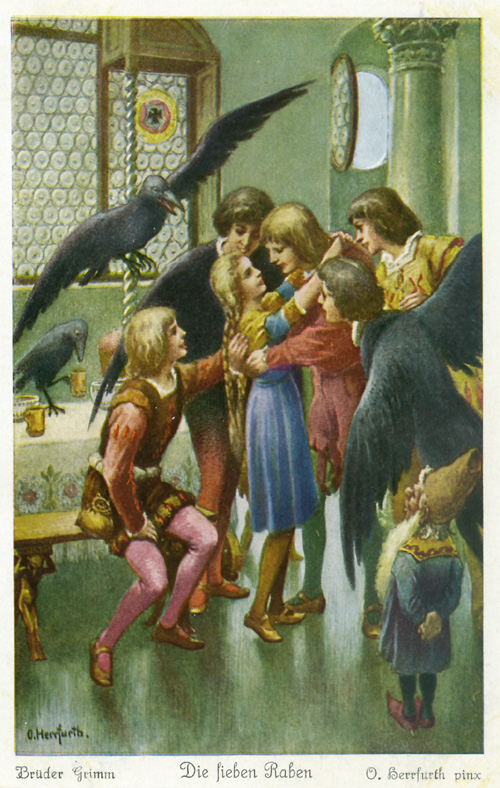

In other tales a sister sets out to rescue brothers she never knew she had. Stories of this kind emphasise a heroine’s self-sacrifice and endurance; Hans Christian Andersen’s ‘The Wild Swans’ is the best-known, but there are many others. In ‘The Seven Ravens’ a sister journeys to free the brothers her father cursed and transformed into ravens at her birth.[5] Visiting first the sun, then a terrifying moon which desires human flesh – and having lost a chicken-bone given her by the morning star, she cuts off her little finger for a key to unlock the door to the Glass Mountain where her brothers live enchanted. In a long Irish tale, ‘Gilla of the Enchantments’, Gilla magically revives her three brothers when their half-sister has cut off their heads.[6] To help them escape she changes them first into seals, then ravens, and finally spends a year and a day sewing shirts of ivy for them, all without speaking a word or shedding a tear. Accused of murder, she is sentenced to be burned (on a very Irish fire made of peat and sheets of paper), but an old man delays the burning, crying that Gilla must be under a geas not to speak. ‘You see that it is not her life that is troubling her, but that she is always sewing’. The three ravens fly down, Gilla throws the shirts over them and speaks:

‘Finn, Inn, and Brown Glegil, show that I am your sister, for in pain I am today.’

Silent endurance for the sake of another makes modern readers uncomfortable. We want our heroines to be kick-ass, not passive – but how passive is this behaviour, really? Considering how many women are still carers of one sort or another, it’s worth asking ourselves if, discovering courage in determined, even obstinate endurance, fairy tales recognise something we have forgotten to value. Is kicking ass over-rated?

Not that kick-ass heroines aren’t to be found in fairy tales. In the Norse tale ‘Tatterhood’, twin sisters are born to a king and queen.[7] The eponymous Tatterhood pops out first, clutching a wooden spoon, yelling, ‘Mamma!’ and riding on a goat. Her ordinarily sweet and lovely twin sister is born second. The parents are ashamed of Tatterhood, but the two sisters love one another and cannot be parted. One Christmas Eve when trolls and witches invade the palace, Tatterhood drives them out, but a witch whips off her sister’s head and substitutes that of a calf. Bursting with self-confidence, ugly sister Tatterhood sets off in a ship with goat, spoon and sister – saves the day, teaches a selfish prince a lesson about beauty, and organises two marriages. I adore the wilful, subversive female energy of this tale. Frozen pales beside it!

In tales featuring three sisters, the elder two generally fall into some scrape such as marrying a murderer or a troll, from whom the youngest and savviest sister will eventually rescue them. The canny heroine of ‘Fitcher’s Bird’ orchestrates the lynching of a wizardly serial-killer and restores her murdered sisters to life.[8] Fiery Highland heroine Maol a Chliobain and her two elder sisters set out to seek their fortunes together.[9] Sheltering overnight at a giant’s house, Maol wisely exchanges the amber necklaces of the giant’s three daughters for the string necklaces she and her sisters wear, so that in the dark the murderous giant kills his own daughters instead of them. Maol escapes with her sisters, robbing the giant of his treasures, and competently marries herself and her sisters to the three sons of a rich farmer. And in the tale ‘The Three Sisters’, the eponymous sisters become poor after they are cursed by an old woman in a red cloak whom they have refused a cup of tea.[10] Each in turn sets out to seek work. The first two girls meet a fairy man in a red jerkin who asks them to pass through a gate and climb a hill. White stones on the path call out to them, ‘Stop and look!’ and when they do, they are turned into white pebbles. The third sister, however, is clever and hardy. By speaking first to the little man, she gains power over him – an interesting magical point with an obvious feminist application! She ignores the white stones calling out to her, confronts the old woman in the red cloak, rescues her sisters, gains bags of gold, marries the fairy man and becomes mistress of the hill and the greatest lady in the land.

Fairy tales such as these celebrate loyalty, the bond between brothers and sisters who support and sustain one another. And perhaps the situations they present are not as fanciful as they appear. They were handed down from a past in which mothers frequently did die in childbirth, fathers did marry again and step-mothers did produce their own offspring, whom it was natural to favour. Siblings might be separated by an age gap, by death, or simply because their parents couldn’t afford to keep them. They might be farmed out to distant relatives, sent miles away to begin apprenticeships or go into service. In large families it might not be unusual to have brothers you had never seen… Fairy tales take stock of such situations and offer the satisfaction of happy endings in stories where long-lost brothers are rescued and brought home, where loving siblings refuse to be parted, and where bold sisters drive off dangers and kill monsters, armed only with quick wits, a little magic, or that fine household weapon, a wooden spoon.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

[1] ‘Cap o’ Rushes’, English Fairy Tales, Joseph Jacobs, Dover 1967

[2] ‘The Juniper Tree’, KHM 47, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Wilhelm & Jacob Grimm, tr. Margaret Hunt, Bohn’s Library 1884

[3] ‘Kate Crackernuts’, A Dictionary of Fairies, Katherine Briggs, Allen Lane, 1976

[4] ‘Brother and Sister’, KHM 11, op.cit.

[5] ‘The Seven Ravens’, KHM 25, op.cit.

[6] ‘Gilla of the Enchantments’, West Irish Folk Tales and Romances, tr. William Larminie, Camden Library, 1893

[7] ‘Tatterhood’, Popular Tales from the North, tr. Sir George Webbe Dasent, Routledge & Sons, 1859

[8] ‘Fitcher’s Bird’, KHM 216, op.cit

[9] ‘Maol a Chliobain’, Popular Tales of the West Highlands, tr. J.F. Campbell, Alexander Gardner,1890

[10]‘The Three Sisters’, XXI Gipsy Tales, ed. John Sampson, Salem House Publishers, 1933