‘There are seven miles of hill on fire for you to cross, and there are seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea.’

In an Irish fairy tale, ‘The King Who Had Twelve Sons’ (in West Irish Folktales, ed. William Larminie, 1893), the hero rides his pony over three-times-seven miles of punishing territory to reach the castle on an island where lives ‘the daughter of a king of the eastern world, with a pearl of gold on every rib of her hair.’

‘Seven miles of hill on fire, and seven miles of steel thistles, and seven miles of sea.’ When I first read this nearly a decade ago, it seemed to me a metaphor not only for the creative effort and difficulty of writing a book, but of life and its struggles in general. Nothing worthwhile comes easy. At the time, as well as writing children’s fantasies for HarperCollins, I was engaged in creating a blog on all things to do with fairy tales, folklore, and fantasy. So I christened it Seven Miles of Steel Thistles and just last year, hey-presto! – with the magical assistance of the Greystones Press, the blog was transformed into a book of the same name: A collection of eighteen essays on fairy tales and folklore.

One of the things I wanted to do in the book was to confront a number of popular misconceptions about fairy tales, such as ‘fairy tales are all about princes rescuing princesses from towers.’ In fact, if you take the two hundred and eleven collected fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, and discount the hundred or so which are really animal fables, nonsense tales, saint’s tales, and so on, almost half of the remaining stories contain prominent female characters who rescue their brothers or sweethearts, save themselves and others, and win wealth and happiness. Fairy tale protagonists of either sex are usually underdogs – orphans, simpletons, the youngest child or step-child – and they succeed by quick wits, luck, and good nature rather than by strength. Trickery, rather than brute force, is the norm. Not only does this put the sexes on an equal footing, but some heroines have the added advantage of being magic-workers – a skill few heroes possess. In the Grimms’ fairy tales alone, there are twice as many heroines who save princes as there are heroes who save princesses.

Another common assumption is that fairy tales always end with wedding bells. Many don’t, while some take a pretty dark view of marriage. Stories about fairy brides or selkie brides often focus on the strain of maintaining an unequal relationship. One partner, usually the husband, is satisfied with the marriage, not realising the bride he has captured or tricked is full of repressed resentment. He breaks a promise or prohibition which after years of union he has come to think trivial, and she leaves him forever. These stories say something deep about the Otherness of even the person you know best.

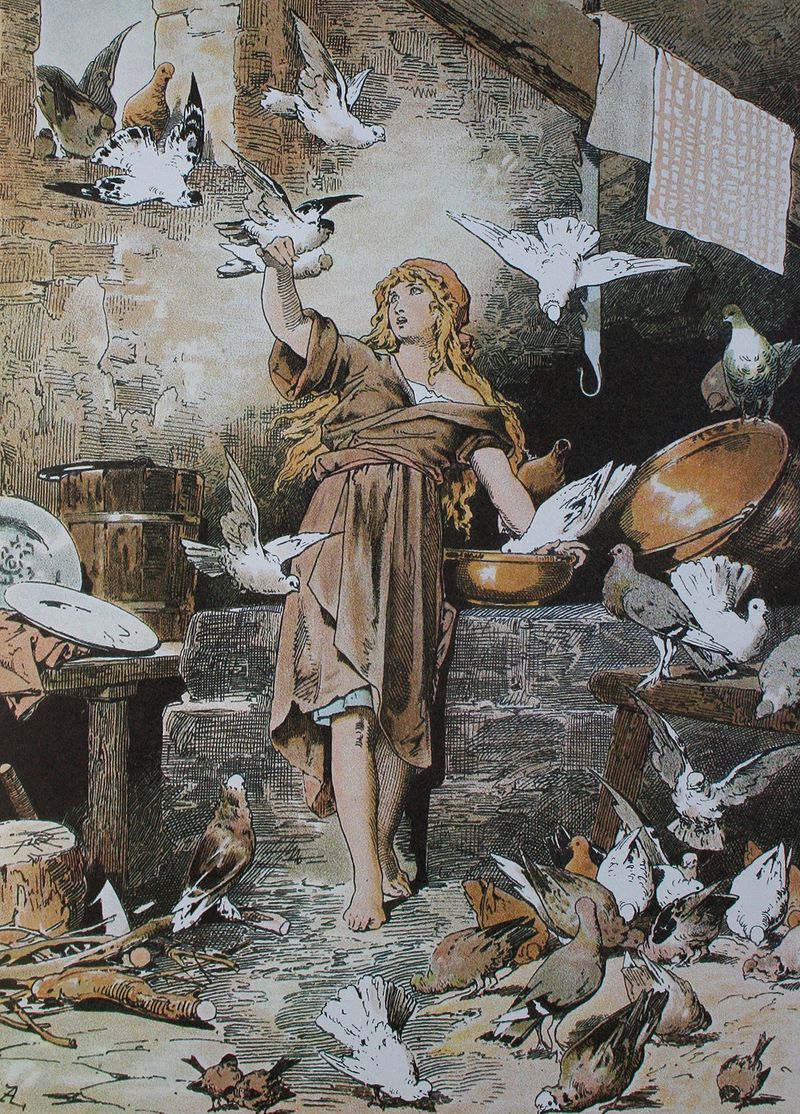

In spite of the cliché of the ‘fairy tale romance’, fairy tales are not romances; the union at the end, when it comes, is often almost perfunctory. Instead they tell of family relationships: weak or incestuous fathers, cruel stepmothers, and bitter rivalry or strong loyalty between brothers and sisters. Some, such as ‘The Juniper Tree’ emphasise the power of a mother’s love; strong enough to extend protection to her child beyond death. In ‘Aschenputtel,’ the Grimms’ version of ‘Cinderella,’ there is no fairy godmother; rather, it’s the tree growing on the mother’s grave which shakes down gold and silver dresses to meet the daughter’s need. The white doves which perch in the tree are emblems of her departed soul.

Seven Miles of Steel Thistles opens with an account of how fairy tales enchanted me as a child. I then move on to themes such as the role of fairy tale heroines (tougher than you think), the uses of enchanted objects (utilitarian kettles and tablecloths, rather than swords or rings), the significance of primary colours (no Disney pinks or purples), and why references to fairy kings, popular in medieval times, seem to die out in Britain after the sixteenth century. In the second section of the book, ‘Reflections on Fairytales,’ I discuss in depth six of my favourite tales – ‘Briar Rose’/’Sleeping Beauty,’ ‘The Juniper Tree,’ ‘The King Who Had Twelve Sons,’ ‘The Great Silkie of Sule Skerry,’ ‘Jorinda and Joringel,’ and ‘Bluebeard’/’Mr Fox’ – contextualising them and examining different versions, while doing my best to account for their remarkable emotional power. In the final section, ‘Reflections on Folk Tales,’ I consider water spirits and White Ladies, look at some of the stories in Thomas Keightley’s wonderful early 19th century compendium ‘The Fairy Mythology,’ and examine Thomas Crofton Croker’s historical account from 1820s Ireland of a wife stolen by the fairies – a haunting tale which turns, like fairy gold, into something very different.

When writing a book, themes often emerge which you hadn’t originally considered. As I came to the end of this one, I found I’d spent a lot of time thinking and talking about the ways in which individual stories change depending on who is telling them and with what motive. Trying to find the ‘original’ version of a traditional tale is a vain search, and the importance of the narrator in the oral tradition cannot be over-estimated. Every person who retells a story changes it in some way and it seems to me that:

“Fairy tales in books are like fossils, or Sleeping Beauty’s castle, preserved in time and growing more and more dated. Fairy tales on the printed page are finished, unchanging, canonical, anonymous. Fairy tales told aloud are fuzzy-edged, fluid, variable – and belong to the person who is telling them, for so long as they are upon his or her tongue.”

On a personal note, the year during which I wrote this book was difficult. Much of my time was taken up with caring for my increasingly frail and much-loved mother. Time for writing was scarce and precious, but then time is always scarce and precious. My mother lived to see the book but not to read it; still, the memories are good, and life comes like the thin blades of green thrusting up through the sooty dust on the scorched hills. ‘Seven miles of hill on fire to cross, and seven miles of steel thistles and seven miles of sea’. Fairy tales acknowledge the difficulties of life, but remain full of hope:

‘He gave his face to the way, and he would overtake the wind of March that was before him, and the wind of March that was after would not overtake him.’

Win a copy of Seven Miles of Steel Thistles by Katherine Langrish

The talented Katherine Langrish has offered a copy of her book for one lucky #FolkloreThursday readerthis month!

Seven Miles of Steel Thistles is a collection of essays on fairy tales and folklore, based on Katherine Langrish’s popular blog of the same name. The essays reflect upon subjects as diverse as fairy brides and Japanese fox-spirits, ghostly White Ladies, the role of fairytale heroines, and what happened to the Lost Kings of Fairyland. She examines a number of specific tales such as ‘Briar Rose’, ‘Jorinda and Joringel’, ‘Bluebeard’ and ‘Mr Fox’, and considers why and in what circumstances people have been prepared actually to believe in fairies.

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid March 2017; UK & ROI only).