Sheep have been integral to British life for thousands of years, and a long tradition of lore has developed around shepherds and their flocks.

Sheep are uniquely suited to the British harsh climate, and by Medieval times the wool trade was driving the economy.

Shepherds spent their lives amongst their flocks, preventing them straying and in earlier times guarding them from thieves and wolves. Their dogs were essential for this, although in more recent times sheepdogs have been used entirely for gathering and droving sheep.

Years of experience were – and still are – needed to detect a slight change in a sheep’s demeanour, unnoticeable to a layperson, which indicates a potentially serious problem if not attended immediately. All remedies were homemade from whatever was available, and developed through centuries of trial and error.

The shepherd’s life could be idyllic in summer, amongst the wildflowers and unpolluted air, but unremittingly bleak in winter when they were trudging miles across wind-blasted hillsides to tend their charges. Shepherds could rarely leave their flocks, even on Sundays to attend church, so they were often buried with a lock of wool in their coffins to signify their profession and avoid an unfair hearing on Judgement Day.

Sheep wore bells in many areas, and the melodic tinkling as they grazed provided music for the shepherds – and an alarm if they were disturbed. The more adventurous sheep, which ranged the furthest, wore the louder bells, whereas the more cautious ones who stayed close to the shepherd wore smaller, more melodic bells. The lead sheep of the flock is still called a bellwether today.

Given the longtime importance of sheep, it is unsurprising that they have helped shape popular language. Rams will charge with incredible force when fighting, and from this we get ‘battering ram’. Black sheep were believed unlucky in most of Europe, although strangely good luck in Britain, so we get the ‘black sheep of the family’. Black animals were linked to the devil, and more prosaically, black wool couldn’t be dyed and was of little value.

Shepherds traditionally counted their sheep in scores (twenties) using special numbers. The words varied across the country; in Lincolnshire, 1-10 were:

yan, tan, tethera, methera, pump,

sethera, lethera, hothera, dothera, dick.

These numbers, commonly used into the 20th century, have similarities to old Celtic languages such as Welsh and Breton, indicating their antiquity. Their soothing rhythm is suggested to be the origin of counting sheep to aid sleep.

A shepherd’s year has always centred on two main events: shearing and lambing. English wool was in high demand in Europe; many towns and churches were built from its profits. The nursery rhyme Baa, Baa, Black Sheep, dating to the 13th century, relates to this, as do pub names such as The Woolpack.

Shearing usually began in June to avoid any dangerous deterioration in the weather. Shear your sheep in May, shear them all away, a rhyme warned.

The sheep were first washed. They were repeatedly dunked in a dammed-up stream or pool until clean. Sometimes a barrel was fixed in the stream for the shepherd to stand in and keep dry. Placenames such as Washbrook or Washpool, still seen on maps, are reminiscent of this.

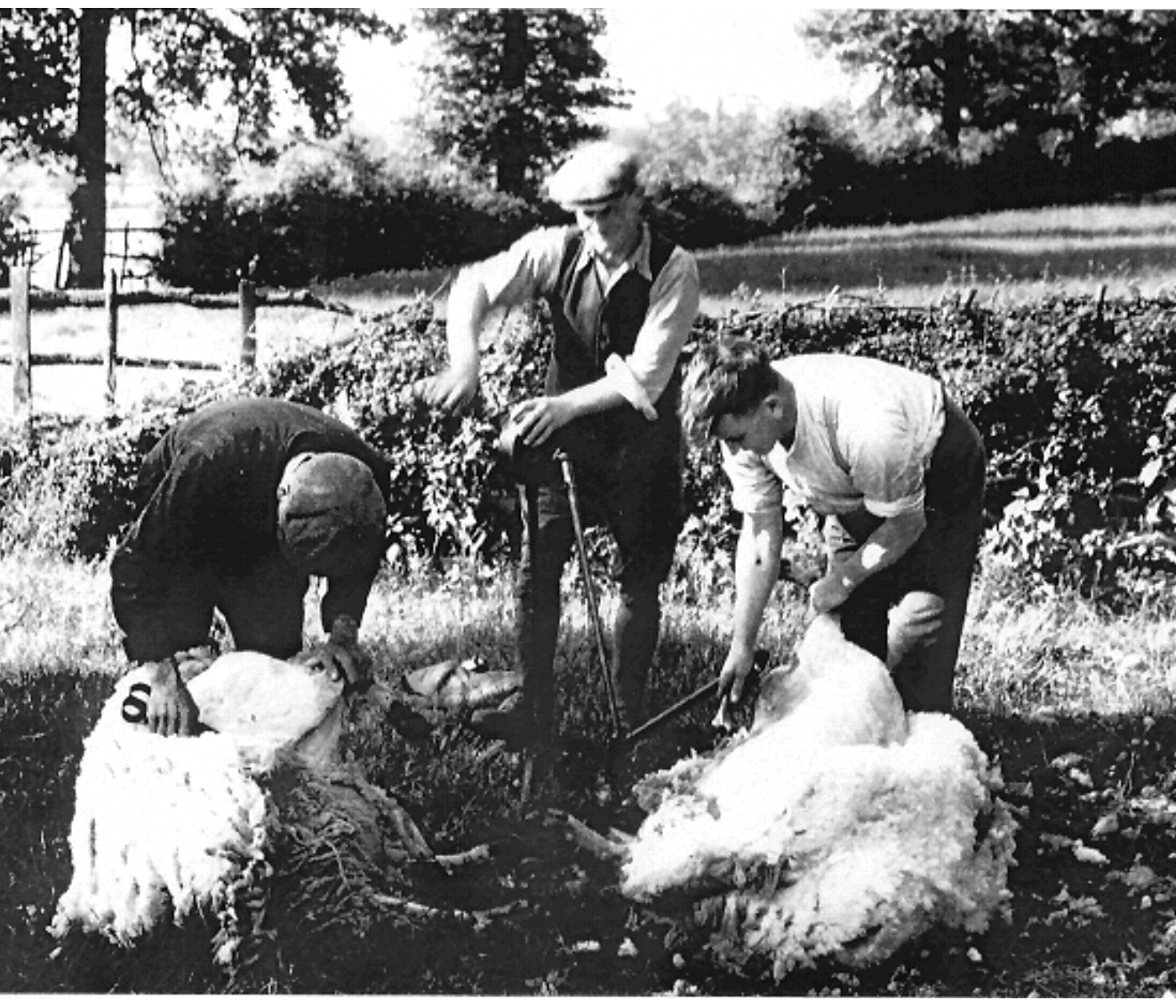

Farmers and shepherds teamed together to work through each flock successively. It was sweaty, backbreaking work, and took skill to clip the wool in a single piece, close to the skin of the struggling sheep, without cutting either animal or shearer. A good shearer aimed to shear at least eighty sheep a day. Hand shears have been in use since at least Roman times; mechanical clippers from the 20th century. Catchers tipped up the sheep and passed them to the shearers; wrappers, often women, removed any dirt or straw from the fleece and rolled it ready for the woolsacks.

After the district’s shearing was complete, a sheep-shearing supper was held. Shakespeare wrote of a sheep-shearing feast in The Winter’s Tale, and they were routinely held into the 20th century, comprising boiled beef, plum pudding and plenty of ale.

In late summer, thoughts turned towards the next lambing season. The old lambs were weaned; the older ewes unfit for breeding again were sent to market; and the rams put with the remainder.

Lambing traditionally began in March, when the spring grass was growing and the weather more favourable. Today, as ewes are housed, it is often in January or February.

Lambing is the most important and stressful event of the year: the shepherd’s livelihood depended on its success. Strict and constant vigilance for sickness, predators and birth problems was, and still is, vital. A mis-presented lamb can die within minutes if not attended at once. If the sheep lambed outdoors, the shepherd lived in a caravan or hut so he was in constant attendance. Others made a basic shelter among thorn bushes – Shepherds Bush in London is thought to originate from such.

Traditions unsurprisingly grew up around lambing. If the first lamb was seen facing you, it meant good luck. If facing away from you, the opposite. It was tradition in Warwickshire villages for the shepherds to have a pancake when the first lamb was born. This is still done in some farming families today.

When lambing was over and the young animals were thriving, the shepherds could relax. In pastoral areas such as Wales and Northern England, this was the end of the farming year and the end of the annual contracts for farmworkers. Annual hiring fairs, called Mop Fairs or Statute Fairs and still surviving as funfairs, were held in May in these districts. The shepherds then had plenty of time to settle into their new flock before lambing began again.

A shepherd of a thousand years ago would barely recognise the sheep of today. Myriad breeds, bigger, meatier and woollier, have been carefully bred for the climate, topography and diseases of their particular district.

But then he would see that they haven’t really changed, and the same skills and experience are needed by the shepherds who tend them. All shepherds, past and present, know the pleasure of finding a pair of fat and contented lambs snuggled up to their ewe on the first day of lambing.

Agriculture may have changed beyond all recognition since the first shepherds tended their flocks on this land, but some things remain ever the same.

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

The Last Shepherds, Charles Bowden, Andre Deutsch, 2011.

The Working Countryside 1862-1945, Robin Hill and Paul Stamper, Swan Hill Press, 1993.

The Farm and the Village, George Ewart Evans, Faber and Faber, 1969.

The Folklore of Warwickshire, Roy Palmer, Batsford, 1976.

Folklore in Shakespeare Land, J. Harvey Bloom, Mitchell Hughes and Clarke, 1930.

English Social History, G.M. Trevelyan, Book Club Associates, 1973.