Perhaps the earliest recorded dairy farmer is the cyclops Polyphemus in Homer’s The Odyssey, who milked ewes and made curd cheese in his island cave around 3000 years ago.

Dairy products, sourced from cows, goats, sheep, buffaloes, reindeer and many other animals, have been integral to life for millennia and in many cultures have been crucial for their survival.

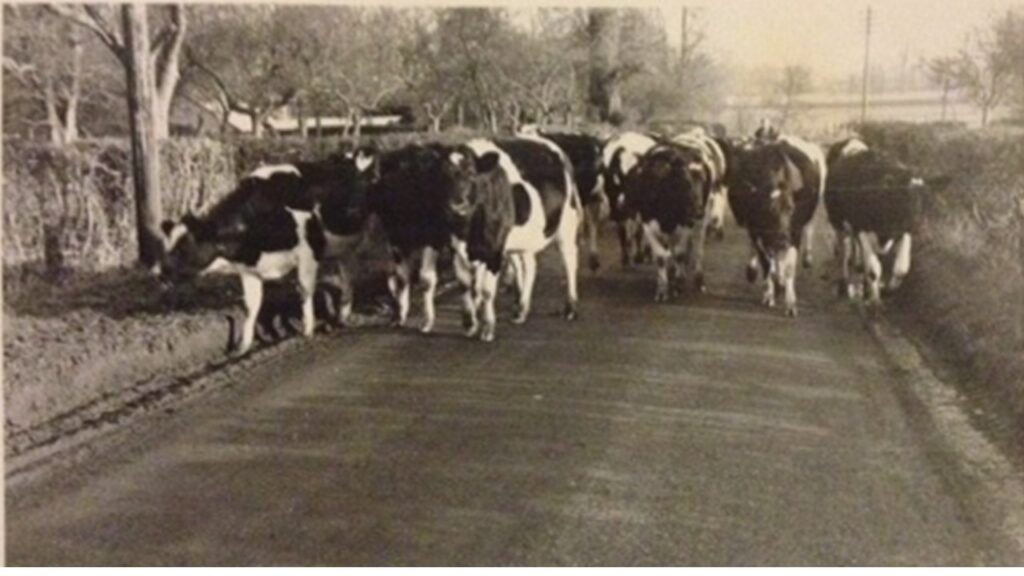

In Britain, cows are the traditional dairy animal. From the Middle Ages, most farms kept a few cows, and landless craftsmen and labourers also aspired to keep a cow which would provide valuable food and a source of income. Cows were grazed on the village common land; when this became largely enclosed into private fields, it was common to see them grazing village greens and roadsides, watched by an old man or a boy.

The first milk given after calving, called colostrum, beestings or cherry curds, is very rich and full of antibodies and nutrients. This was traditionally made into a custard-like pudding and believed to keep children healthy throughout the year.

If a cow lost her milk, it could prove disastrous for a hard-up family. Witches and fairies were often blamed for this. It was commonly believed that witches took the form of a hare and suckled cows dry during the night. Hedgehogs were also accused of this. A now uncommon bird called the nightjar was colloquially called ‘the goatsucker’, for its unsubstantiated habit of suckling milk from goats.

Bewitched cows would suddenly lose condition, give curdled milk or milk filled with blood. Horseshoes and rowan twigs were fixed above cowhouses to ward off malign influence, and folklore abounds with tales of bewitched cows suddenly cured by such techniques. Today, many of these problems would be attributed to mastitis, an udder infection easily treated with antibiotics.

Cows were, and still are, milked twice a day, seven days a week. It takes around ten minutes for a skilled milker to milk a cow by hand; much longer for a novice. Until the invention of automatic milking machines, a herd of twenty cows was a huge undertaking. Women were considered the best milkers. They were quieter and gentler, and the cows were believed to yield better. It needed a lot of patience to milk a bad-tempered cow which would kick both milker and bucket, often seeming to deliberately wait until the bucket was full! In many areas, milking became the cowman’s job by the 20th century and women were limited to the indoor dairy work.

Before the advent of the railway network, there was little market for liquid milk – it soured long before it reached its destination – and much was turned into butter or cheese. Making hard or farmhouse cheese was a long, skilled process limited to the bigger houses and farms, and most cottagers made a simple curd cheese or ‘cottage cheese’. Long handed down local techniques produced the dozens of traditional regional cheeses we know today.

Dairy work was a woman’s job. Men were believed to lack the necessary patience and care. Many rural women were skilled with all aspects of dairy work. It was hard, physical work. Cheeses weighing up to 50kgs were lifted and turned daily. Dairymaids were expected to be at work by 5am and could be at the churn for four hours a day, churning the cream until it turned to butter.

The correct churning speed was essential. Men were inclined to churn too fast and produce soft, poor quality butter. Churning songs gave the correct speed and amusement:

Come, butter, come.

Come, butter, come.

Peter’s standing at the gate,

Waiting for a buttered cake.

Come, butter, come.

Sometimes, the butter didn’t come. This was typically blamed on witchcraft, mischievous fairies or boggarts. If the butter had been ‘witched’, plunging a red-hot iron poker into the churn would drive out the offending entity. A silver spoon or coin placed in the churn could also drive out a witch. Rowan sticks and horseshoes were often placed under the churn as a safeguard. Visitors who arrived when the butter was being churned should say ‘Bless the work’, else when they left the butter would leave with them and would never come.

In the late 19th century, scientists discovered that the temperature, age and acidity of the cream, the condition of the cows, and ambient weather conditions all influenced whether the butter came. That red-hot poker may have done the trick after all.

Once the butter came, it was washed and worked to remove all traces of buttermilk. Mechanical butter workers appeared in the late 19th century, but the famous cookery writer Mrs Isabella Beeton wrote that no butter worker could equal a woman’s hand. But conversely, no woman with hot, clammy hands should ever be a dairy maid as she would always produce inferior quality butter.

Advances in science and technology had a dramatic impact on dairy work. Railways transported milk to towns and cities. Factories produced butter and cheese on a huge scale. Dairy schools taught women new, scientific procedures vastly different to those they’d learnt from their mothers and grandmothers. Careful breeding, improved fodder, development of antibiotics and other medicines increased milk yields. The automatic milking machine speeded up the milking process so herd sizes could expand. By the 20th century it was no longer viable or necessary to process milk on the farm. The vast array of age-old techniques and dairy lore largely died out.

The wheel has now gone full circle. The techniques and recipes for long-forgotten farmhouse cheeses are being rediscovered and are ever more in demand. Thankfully, traditional, hand-crafted cheeses are again returning to our shops and kitchens.

Dreamweaver by Hannah Spencer

Hannah Spencer has offered a copy of her excellent new novel, Dreamweaver, for a lucky Patreon supporter this January!

“The dreams of some create the realities of others. Some of those dreams are laced with hope; others with poison. Centuries ago, two women used the powers of their family talisman, an ancient crystal skull, to protect their loved ones in a bloody war. But its gifts had a price, and their ghosts linger in the ruins of their family home, waiting for atonement to be made. When their descendant Jemima discovers the skull, she becomes increasingly manipulated into a web of dreams and nightmares. Her ancestors are fighting to free themselves from their curse, and watching them all, the skull is waiting to claim its due.”

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter here to enter our competitions this month,

or become a Patreon supporter and be eligible for Patreon gifts here.

The book can be purchased here.

References and Further Reading

The Odyssey, Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald, 1965

Lore of the Land, by Jennifer Westwood and Jacqueline Simpson, 2005, Penguin

Beeton’s Book of Household Management, by Isabella Beeton, 1861

The English Dairy Farmer 1500-1900, by G. E. Fussell, 1966 Frank Cass & Co Ltd

Folklore, Old Customs and Superstitions in Shakespeare Land, by J. Harvey Bloom, 1930, Mitchell Hughes and Clarke

The Folklore of Warwickshire, by Roy Palmer, 1976, B. T. Batsford