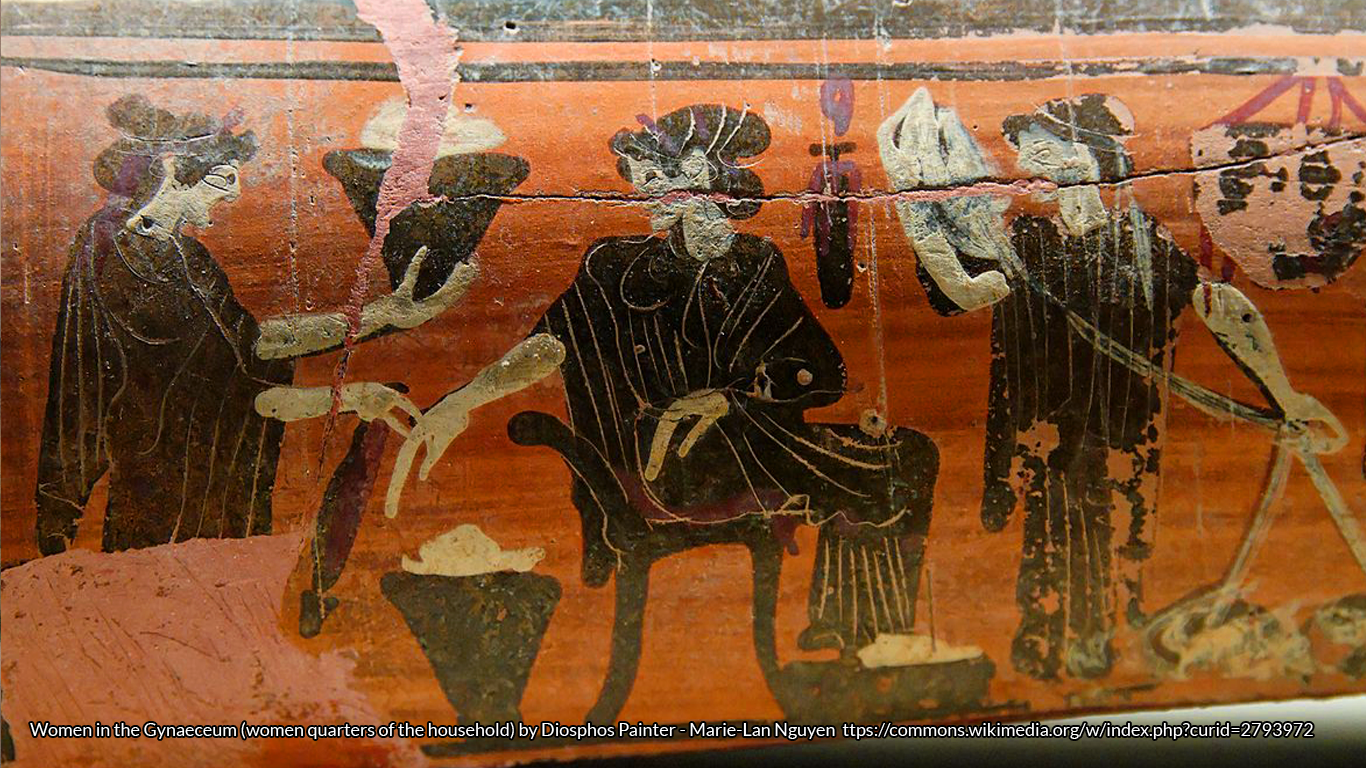

The idea that the womb wandered about the female body was prevalent in antiquity, even after it was disproven by some ancient physicians. Women diagnosed as suffering uterine suffocation (hysterike pnix) or hysteria were thought to be experiencing a condition whereby their womb had left its set place, and had begun to move about the body, thereby causing havoc. The causes of the wandering womb were thought to stem from women deviating from their social roles; for instance, women who did not conceive and give birth regularly. To cure the wandering womb, ancient doctors and magicians employed techniques that crossed over between medical and magical.

The earliest written records on the wandering womb date to the 5th and 4th Centuries BC in the works of the Hippocratic School, such as Diseases of Women, and Plato’s Timaeus. It is likely, however, that the idea is much older and accounted for the madness and hysterical characteristics of women in Greek myth. In the Timaeus (91a-d), the womb is described as a frenzied animal with an irresistible drive to reproduce. When not with child or in the act of trying to reproduce, it was thought to wreak havoc throughout the body, thrashing into various organs. The Hippocratic writers also discussed the wandering womb but did not directly compare the womb to an animal; instead focussing on the symptoms and causes.

To prevent the womb wandering about in the first place, they instructed that women should marry young and attempt to conceive often, so the womb would be too moist and/or heavy to move about. In the case of the womb already being displaced, doctors were advised to use (among many other techniques) sweet and foul-smelling fumigations to encourage the womb to return to its place. Depending on the current position of the womb, sweet smells were used to attract the womb back to its place while foul smells like pitch or burning wool were used to drive the womb away from a particular location (2.123).

After the development of human dissections in the 3rd Century BC, many doctors were informed that the womb was held in place by ligaments, and thus could not wander about the body. The ancient physician Soranus of the 2nd Century BC was also sceptical and criticised the medical writers who promulgated the theory. Nonetheless, the idea of the wandering womb continued to influence the treatment of patients by ancient doctors, and also magicians, for hundreds of years. The medical discoveries that disproved the theory of the wandering womb seemed to have little to no effect on society.

The belief that illness and disease were inflicted by external, supernatural forces was common in ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern cultures. Following the impression that the womb was animalistic, the idea of it as a demonic creature emerged. The troubles caused by a wandering womb were accordingly placed into the category of demon-induced illness in the context of ancient magic, and a magician or exorcist was employed to use ritual techniques to drive the demon out of the body. Like the earlier Greek doctors, fumigations were sometimes used to expel a demon. As the womb could not be exorcised because it was needed to reproduce, magicians and exorcists ordered the womb to return to its place through a magical adjuration. These adjurations were either verbally recited, written down on an amulet, or both.

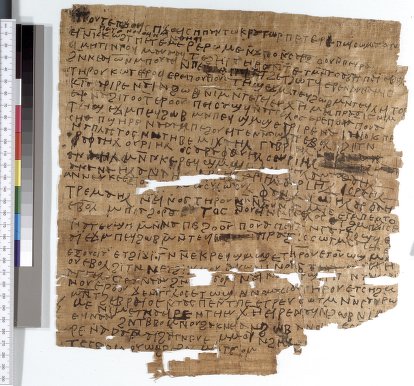

The spell “For the Ascent of the Womb,” otherwise referenced as PGM 260-71, is part of the Papyri Graecae Magicae (or Greek Magical Papyri). The Greek Magical Papyri is a collection of papyri discovered in Egypt that was most likely the personal handbook of an ancient magician. It dates back to approximately the 4th Century AD, containing spells that would have been copied out and handed to clients for a range of purposes and requests. This particular spell to cure the wandering womb reads as follows:

“I conjure you, O Womb, [by the] one established over the Abyss, before heaven, earth, sea, light, or darkness came to be; [you?] who created the angels, being foremost, AMICHAMCHOU and CHOUCHAO CH~ROEI OUEMCHO ODOU PROSEIOGGBS, and who sit over the cherubim, who bear your (?) own throne, that you return again to your seat, and that you do not turn [to one side] into the right part of the ribs, or into the left part of the ribs, and that you do not gnaw into the heart like a dog, but remain indeed in your own intended and proper place, not chewing [as long as] I conjure by the one who, in the beginning, made the heaven and earth and all that is therein. Hallelujah! Amen!”

Write this on a tin tablet and “clothe” it in 7 colors.”

Here the womb is addressed directly and ordered to return to its proper place. The concept of the womb being like an animal, in this case a dog, demonstrates the persistence of this idea through time. The magician attempts to frighten the womb into following his orders by calling upon the Jewish god and angels for support. The names of the angels are written as mystical words, like “abracadabra,” to make the spell work. The language used is typical of spells for exorcising or casting out demons from the body, sending them back to their own domain.

The spell is to be written on a tin tablet and clothed in 7 colours. The number 7 was perhaps chosen because it is an odd number, and in Jewish belief odd numbers were lucky and could be employed in spells to drive demons away. Additionally, ancient Greeks believed odd numbers to be ‘masculine’ and thereby capable of defeating the ‘feminine’ when employed in spells. This would make sense considering that conception and pregnancy are required to control the wandering womb.

The wandering womb was a persistent idea in the ancient world, and both doctors and magicians worked to cure this problem even centuries after the theory had been medically disproved. A woman needed to fulfil her social role as procreator, and there were consequences when she failed to do so. In cultures where men were not held responsible for infertility, it seems that every method to cure a woman of a wandering womb was employed – even magical ones.

References & further reading

De Bruyn, Theodore S., and Jitse H.F. Dijkstra. “Greek Amulets and Formularies from Egypt Containing Christian Elements: A Checklist of Papyri, Parchments, Ostraka, and Tablets.” The Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists, vol. 48, 2011, pp. 163–216.

Faraone, Christopher A. “Magical and Medical Approaches to the Wandering Womb in the Ancient Greek World.” Classical Antiquity, vol 30, no. 1, 2011, pp. 1-32.

James, Sharon L, and Sheila Dillon. Companion to Women in the Ancient World. Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

Jones, Cara E. “Wandering Wombs and “Female Troubles”: The Hysterical Origins, Symptoms, and Treatments of Endometriosis.” Women’s Studies, vol 44, no. 8, 2015, pp. 1083-1113.

Kotansky, Roy. “Greek Exorcistic Amulets.” Ancient Magic and Ritual Power, Marvin Meyer and Paul Mirecki, Brill, Netherlands, 1995.

Scarborough, John. Trans. PGM 260-71. In H. D. Betz (ed.). (1992). The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation, Including the Demotic Spells. 2nd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 123-124.

Trachtenberg, Joshua, and Moshe Idel. Jewish Magic and Superstition. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc., 2012.