A project cataloguing the archive of a renowned British palaeopathologist has revealed fascinating insights into how superstition and a belief in magic influenced ancient peoples’ approach to medical diagnosis and treatment.

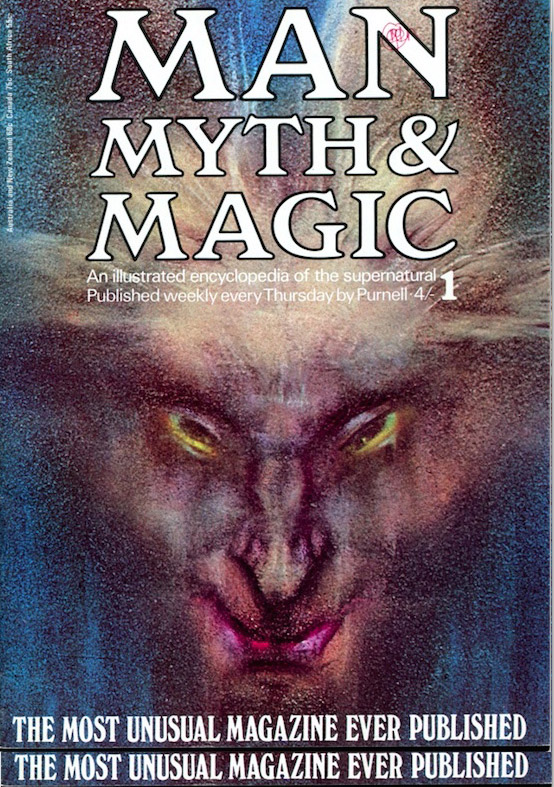

In an article titled ‘Disease’ in the popular 1970s periodical Man, Myth and Magic: An illustrated encyclopaedia of the supernatural Wells makes the case that ‘magic and medicine have been inextricably mixed since humanity first tried to cure disease’. The earliest forms of medicinal treatments, Wells contests, were dictated by what came to be known in medieval times as the ‘Doctrine of Signatures’. Its central belief being that natural objects that looked like a part of the human body could cure any diseases that would arise there. Wells notes that the evidence for this ‘like cures like’ approach to medical treatment appears deep in the archaeological record. He gives the example of 200, 000 year old Neanderthal burials which contain bones coated in red ochre. While debate continues about the reasons why Neanderthals used red ochre in their funerary practices, Wells argues that it was a form of prehistoric homeopathy in which the deep red pigment was thought to ‘embody the life-giving potency of blood’.

It was not just in the creation of medicinal cures in which a belief in magic played a role. One of the earliest forms of surgery, known as trephination, was also rooted in a faith in the supernatural. This ancient surgical procedure was of such interest to Wells that he devoted an entire chapter of his book Bones, Bodies and Disease to the subject. In it he writes:

“Few subjects fascinate me more strangely than pre-historic trephination. Even today, with every help science can offer, an operation to open the skull remains a pageant of drama and suspense and we are right to marvel at the Neolithic patient who risked his life beneath the surgeon’s flint.”

There are many theories about the practice of trephination, which first appeared in the Neolithic period. A popular explanation is that the burr hole was made to set free malevolent spirits causing illnesses such as migraines or epilepsy. In some instances the removed disc, or rondelles, have been found with pierced holes suggesting they were used as some kind of magical amulet or charm. Cases of trephination have been discovered around the world, and Wells even wrote a report in the journal Antiquity about five trephined Anglo-Saxon skulls found in his home county of Norfolk. In the report Wells suggests that each of the trephinations was performed by the same surgeon using some form of gouging tool — ‘an excellent instrument for performing trephinations’. In his typically florid style Wells concludes his report by complementing the Anglo-Saxon surgeon’s trepanning technique; calling him ‘a master of the gliding gouge’.

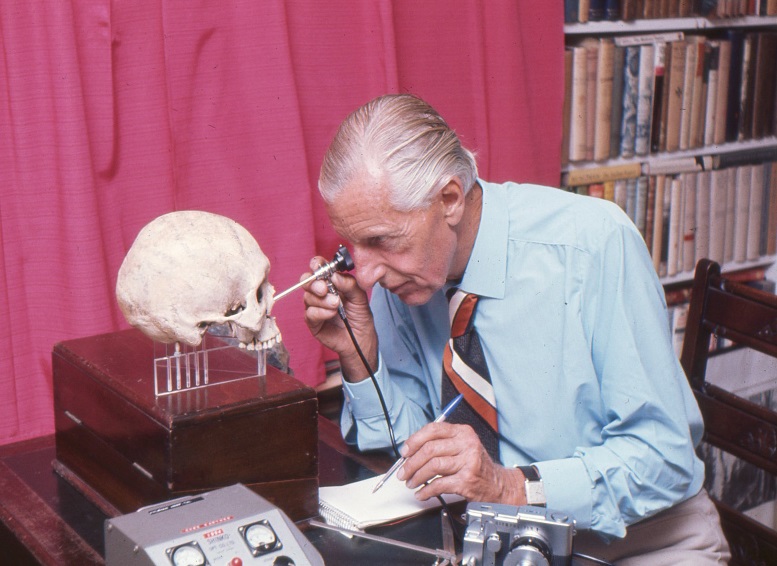

As the UK’s leading palaeopathologists in the 1960s, Wells’ expertise was in high demand among archaeological organisations, university departments and museums. Working from his cottage in suburbs of Norwich, Well received skeletal material in the post which he examined in his kitchen or, weather depending, garden. A feature of Wells’ analysis was his willingness to look beyond skeletal remains for information, coining the phrase ‘never trust a bone alone’. As such, Wells often examined secondary material, such as the representation of disease in artwork, ornaments or ceremonial artefacts. One of the final reports Wells completed before his death in 1978 was an analysis of 8,000 terracotta votive offerings excavated at Ponte di Nona outside Rome by renowned archaeologist T.W. Potter.

A votive, or ‘ex-voto’ is an offering to a saint or divinity given in fulfillment of a vow, or in gratitude or devotion. One of the most common types is known as ‘ex-voto anatomica’, which are modelled on parts of the human body. Such magical charms are often created to cure or prevent disease and injury within societies that exist in insecure environments. Within the rural farming communities of Ponti de Nona, worshippers most commonly crafted clay hands and legs indicating there was high incidence of injury to those body parts in that area. In the article Wells defends the limitations of diagnosing illness in terracotta artefacts, writing ‘it is better to infer a range of possibilities than retreat into a safe but unhelpful silence, making no attempt to interpret these interesting objects’.

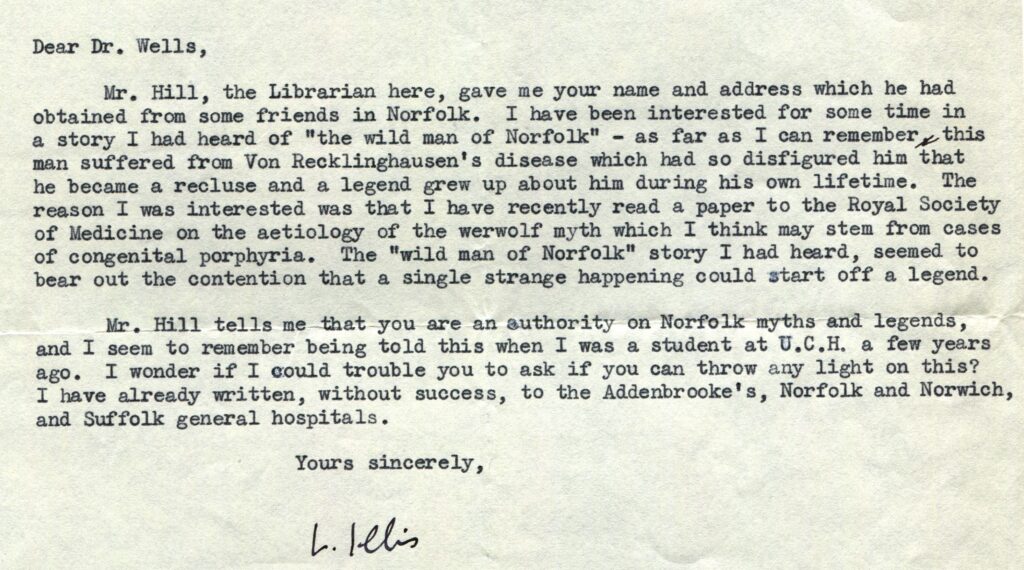

Wells’ research on how a belief in magic imprinted itself on the early history of medicine brought him into contact with authors who frequently wrote on ancient customs and superstitions. The Calvin Wells Archive holds correspondence from a number of renowned folklorists, including Barbara Freire-Marreco, Hilda Ellis Davidson and Ellen Ettlinger. One particularly interesting letters in the collection is from Dr L.S. Ellis, medical physician and author of an article titled On Porphyria and the Etiology of Werewolves. In the course of researching the article Illis came across the legend of the ‘Wildman of Norfolk’ and was curious if Wells knew its origins. Wells agreed with Illis that Norfolk’s ‘Wildman’ possibly had Von Recklinghausen’s Syndrome, a genetic condition which was also believed to have afflicted Joseph Merrick, otherwise known as the ‘Elephant Man’. In pre-scientific times, diseases with inexplicable symptoms were often blamed on supernatural influences and may be the root of various monster myths — such as werewolves and wildmen. In replying to Illis, Wells noted the link between this myth with an historic Norwich pub The Wildman — the palaeopathologist was also a published expert on the etymology of English pub names.

Upon early assessment the Calvin Wells Archive and Library seemed to be chiefly a bio-archaeological science resource with material that includes skeletal analysis and data, burial photographs and radiographs, and site maps and plans. However the cataloguing project has revealed that there is considerable amount of material related to anthropology and folklore, particularly in regards to how ancient people approached disease and injury. One of the cataloguing project’s primary achievements as been uncovering the multi-faceted research value of the material and making it accessible to future generations of researchers. Once catalogued and available online we hope that researchers from across the academic spectrum will engage with the Calvin Wells Archive at the University of Bradford.

References and Further Reading

Wells, Calvin (1964) Bones, Bodies and Disease (London: Thames & Hudson)

Wells, Calvin (1970) Disease in Man, Myth & Magic: An illustrated Encyclopedia of the supernatural Issue 23 (BPC Publishing Ltd.)

Wells, Calvin (1971) Man in His World Calvin Wells (London: Baker)

Well, Calvin (1974) Probable trephination of five Early Saxon skulls in Antiquity Vol. 48. pp. 298-304

Roberts, Charlotte and Manchester, Keith (2012) Calvin Percival Bamfylde Wells (1908–1978) in The Global History of Paleopathology: Pioneers and Prospects Ed. Buikstra, Janes and Roberts, Charlotte (New York, NY: Oxford University Press)

Illis, L.S. (1964) On Porphyria and the Ætiology of Werewolves in Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine Vol. 57. pp.23-6