Hidden in plain sight for a century, two recently reappraised Cottingley Fairy photographs bring a whole new dimension to the celebrated hoax.

Looking back at my old school photographs, I changed a lot between the ages of ten and thirteen. I don’t think it is just a girl thing; it is one of those times of life when everyone makes a huge developmental leap.

So, if someone showed me photographs of a ten year old girl and the same child at thirteen, and the pictures were virtually identical, I would be dubious. I would think the photographs must have been taken at or near the same time, possibly a year apart, but no more than that.

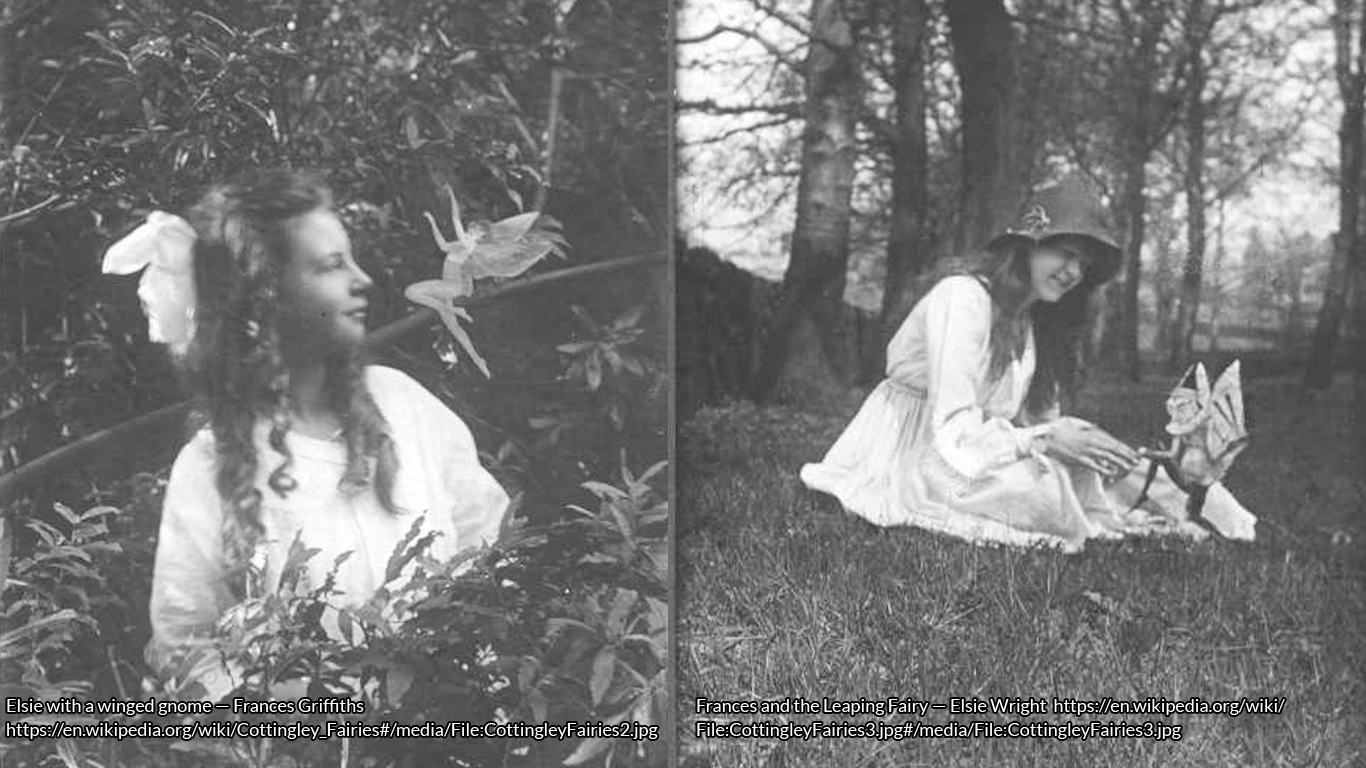

Look at these two pictures of a young girl.

This first image (above) was allegedly taken in 1917 when she would have been ten; the second was definitely dated as being taken in 1920 (view the second image here).

See much difference? Me neither.

If we agree there must be less than three years between these two photographs, what does that mean and how does it impact upon the affair of the Cottingley fairies? For this is Frances Griffiths, cousin of Elsie Wright, one of the two girls who became famous for photographing fairies.

Here I have to admit that I have never believed in the Cottingley fairy photographs – not even the celebrated fifth photograph with its ‘hidden faces’ in the grass. That was dismissed in the 1980’s by photographic expert Geoffrey Crawley as being a simple double exposure.

However, I am not out to upset those who hold abiding beliefs in the Fae; there is better evidence from Ireland and Iceland where the locals fiercely defend fairy territories from modern development. I am simply loosening hopeful fingers from clinging onto these already discredited photographs.

In 1918, The Sphere, a very popular publication, printed the above photograph of a young girl in a sunny London garden. She was sitting by a hedge with what looked like paper cut out of fairies arranged around her. The picture made no attempt to pass these figures off as real fairies. As the edition is dated April 1918, the photograph was probably taken the previous summer, in 1917.

I believe it is this picture that gave Arthur Wright, Elsie’s father and a keen amateur photographer, the idea to photograph fairies. It was not beyond Elsie to take the photographs herself – she had been working at a photographers in Bradford from the age of 15, but it was Arthur who owned the darkroom and a range of cameras. He claimed the pictures were taken in 1917 and then stuffed in a drawer and ‘forgotten’ for two years, but how likely is that?

Arthur may have copied The Sphere photograph to get his own printed in the newspapers and gain some remuneration plus the satisfaction of knowing he had taken far superior pictures to the original. However, the hoax really took off when Elsie’s mother took the photographs to a meeting of the Theosophical Society in 1919. Here is the crux of the matter – the Cottingley fairy photographs were not seen outside the immediate family until a year after The Sphere publication.

Months later, the pictures came to the attention of Edward Gardner, a leading light in the Theosophical Society. Gardner took the photographs on a lecture tour – he sold copies of them at one shilling and sixpence for a small copy and two shillings and sixpence for a large print. At that time two and six was the average weekly wage of a farm labourer, so these pictures were not cheap.

This is where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle enters the story. His cousin saw one of Gardner’s lectures and sent copies of the sensational photographs to Sir Arthur, confiding that she thought them too good to be true.

Initially Doyle was also dubious, but when he finally believed, it is recorded that Arthur Wright became scornful. If Wright had been the main hoaxer, he would also have been a very worried man. Money had changed hands: £5 for the temporary publication in The Strand magazine and a further £5 for the American version. That is around £450 by modern standards. Could this be a motive for Wright to persuade the girls to say they had taken the pictures? After all, two young girls were less likely to be sued for fraud than an adult. Along the way, Gardner sent Elsie and Frances new cameras and other gifts. Even more money was to come when Doyle presented Elsie with £100 for her wedding, the equivalent of over £4,000 now.

Poor, deluded Doyle had three main reasons for wanting to believe. He saw these photographs as beckoning the wider world to accept the supernatural – and mediumship in particular. His adored father spent his days painting fairies in a lunatic asylum, so proof of fairies would have gone some way to redeem this apparently eccentric past time. Finally, as a trained opthalmologist, Doyle simply believed children could see further than adults. Youngsters certainly have more acute hearing than adults, so superior eyesight was not such an unreasonable theory.

I cannot prove that Arthur Wright took the photographs or convinced the girls to front the hoax for him – even with a century of hindsight, it is still difficult to prove or disprove anything. I have simply approached this matter from another angle. I maintain that Frances’ failure to noticeably mature from one set of photographs to another is, at best, suspicious.

See the full story with not one, but two ‘new’ photographs that have been hiding in plain sight for almost a hundred years in ‘The Secret of the Cottingley Fairies’ by F.R.Maher, available on Amazon.co.uk.