From its beginnings in the 1840s until the late twentieth century it was Shakespeare’s Three Witches who inspired the majority of cartoons featuring witches in Punch.

Crouched round a cauldron bubbling with whatever was the latest toxic political stew, it was the Three Witches who Macbeth encounters on a ‘blasted heath’ (and prophesy his fate) which inspired Punch cartoons for over a century. But rather than the female witches of Shakespeare’s play, Punch’s political ‘Weird Sisters’ were almost invariably men. By the end of the twentieth century Macbeth’s Three Witches were no longer a favourite theme for political cartoons, but were still a fertile source of inspiration for some brilliant gags.

Looking back to the early years of Punch, in 1848 John Leech’s archetypal John (Mac) Bull, a wide-eyed rail traveller, complete with satchel, umbrella and muffler, encounters the Three Witches of the Great Western, South Western and North Western Railways near a tunnel at midnight – as the accompanying poem tells us. The horrible trio huddle round a boiler with the steam up, and a railway whistle shrieks at intervals. Though the Railway Mania of the earlier 1840s had subsided, all was still not well in the railway industry – at least not for long-suffering passengers like John Mac-Bull, who listens as the three hags recite their chant, much of which sounds all too familiar to rail travellers today:

Heavier fares and fewer trains;

Public loss and Railway gains;

Third-class trucks like Noah’s ark,

For clean and unclean, damp and dark;

No more day tickets up and down,

For people who live out of town;

A Private Act that guarantees

Our power to treat folks as we please…

Bubble, bubble without trouble,

Fares increase and profits double!

!["How Shall We Three Meet Again?" [Macbeth adapted]](https://folklorethursday.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/3_1885.12.05.271.jpg)

During the first half of the twentieth century David Lloyd George dominated British politics and the Liberal Party for decades. He was the subject of scores of full page political cartoons in Punch, so many that a compilation of them was published in 1922. Yet despite being popularly known as the Welsh Wizard, Lloyd George was rarely depicted in the magazine as an actual wizard, apart from Welsh Wizardry – A Revival of March 1929. The cartoon followed the launch of Lloyd George’s policy document We Can Conquer Unemployment which was to form the basis of the Liberal Party’s campaign in the approaching general election. The Liberal policy promised to reduce unemployment through sweeping national development schemes in sectors like house building and road construction – plans which had the support of such leading economists as John Maynard Keynes.

The cartoon by Punch’s chief political cartoonist, Bernard Partridge, shows the Welsh Wizard riding high on a broomstick, pulling along behind him deputy party leader Herbert Samuel and Liberal stalwart Walter Runciman to sweep away the cobwebs of unemployment. But despite these ambitious forward thinking policies, the Liberals failed to do well at the election which resulted in a minority Labour government.

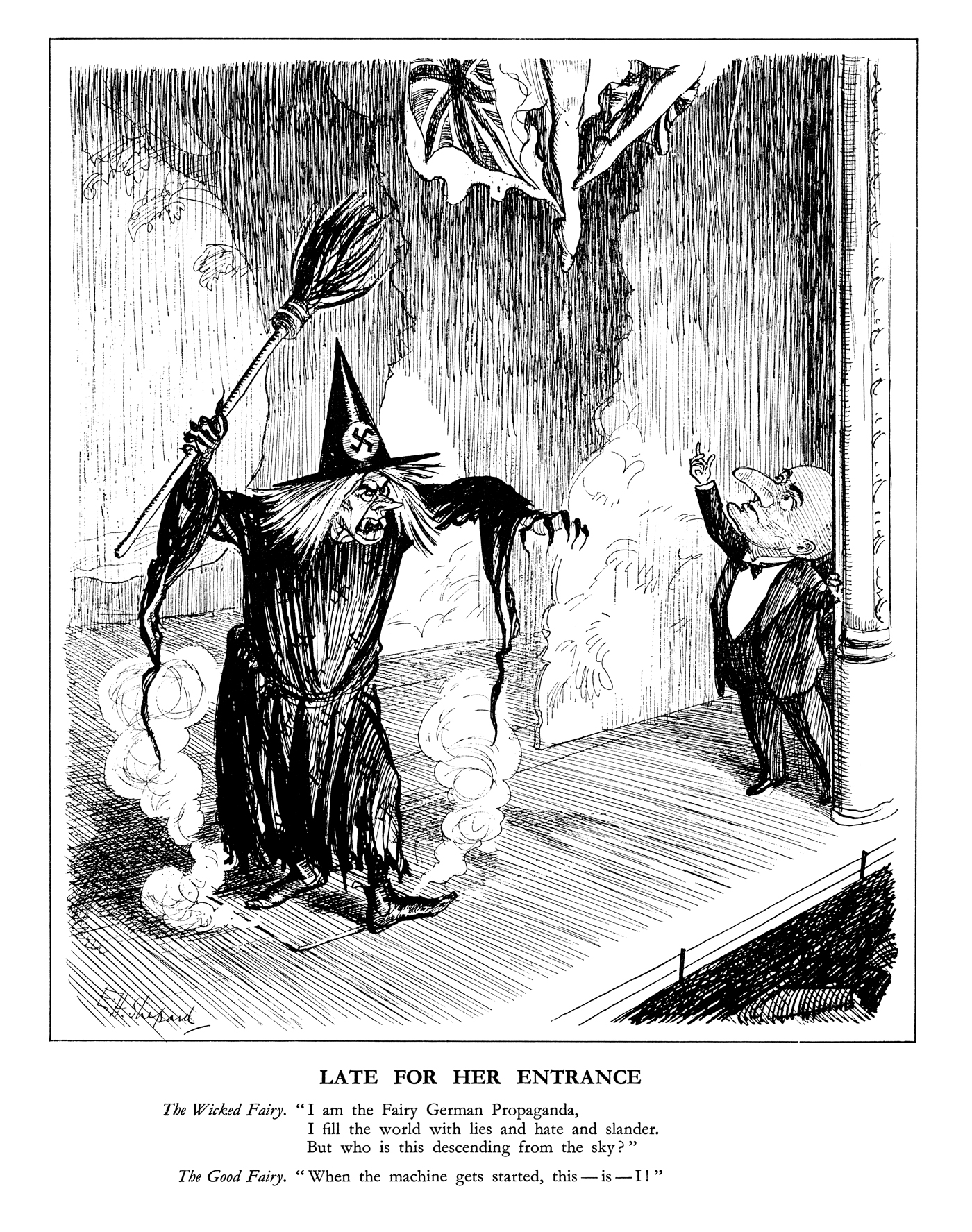

Throughout the 1930s Punch had alerted the public to the dangers of Hitler and Nazism and actively opposed Neville Chamberlain’s policy of Appeasement. War had already been declared against Germany when Punch published Late for Her Entrance by E H Shepard (then Punch’s second political cartoonist) in January 1940. The cartoon depicted the German propaganda machine in the guise of a witch-like Wicked Fairy filling the world with lies, hate and slander. But the legs of a Union-Jack clad Good Fairy who will oppose this propaganda can be seen dropping onto the stage – rather late in the day, according to Mr Punch who stands watching in the wings.

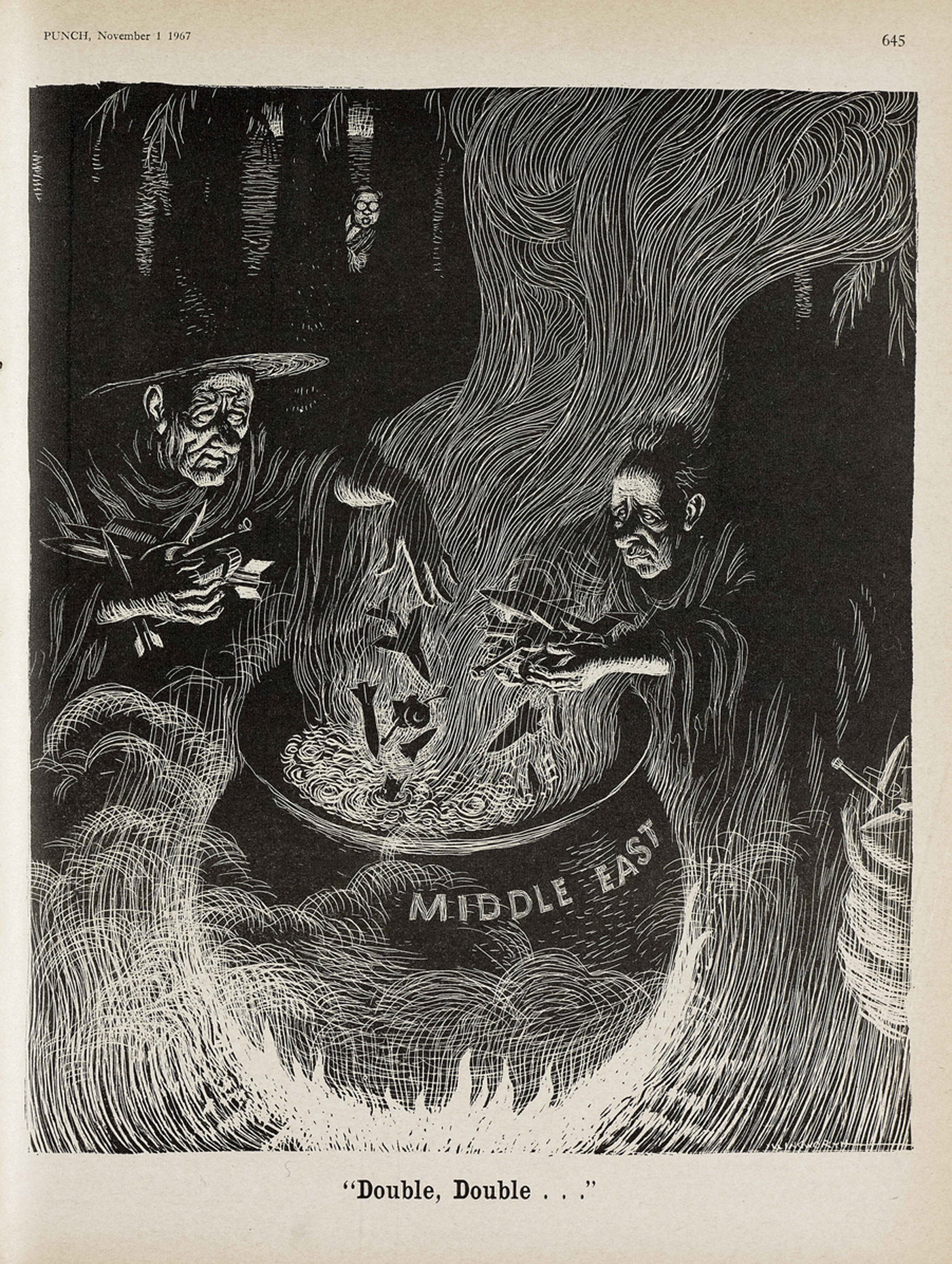

In November 1967 Leslie Illingworth used the theme of Macbeth’s Weird Sisters – one he had used before. But this time there were only two ‘witches’: American president Lyndon B Johnson and Soviet premier Aleksei Kosygin throwing handfuls of military hardware into the boiling pot of Middle East politics. The cartoon is one of the finest of Illingworth’s superbly dramatic scraper-board drawings for Punch.

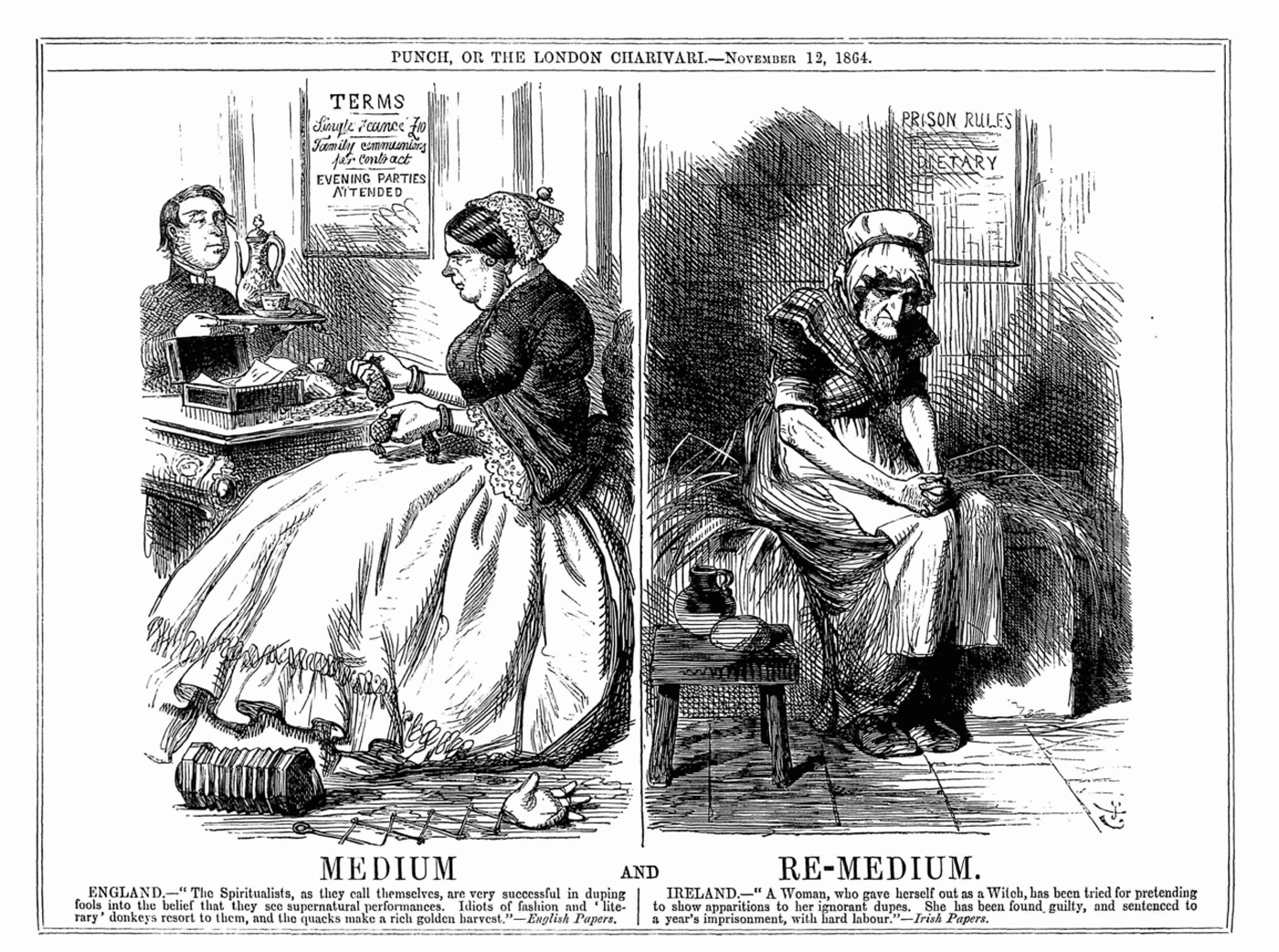

There were relatively few other depictions of witches in Punch until they became a theme taken up by gag cartoonists in the 1980s and 1990s. But in November 1864 the magazine published Medium and Re-Medium by John Tenniel, contrasting the treatment of the fashionable professional medium who was able to extract substantial money from the gullible middle classes for her ‘supernatural’ performances without problem, with that of a poor Irish woman who called herself a witch and who for similar claims was sentenced to a year’s imprisonment with hard labour.

In the twentieth century witches began to appear as a theme in gag cartoons. One of George Morrow’s Little Worries of the Middle Ages from 1910 shows an archer who has shot a witch’s cat in the midst of being transformed into a tree by the angry witch. The power of transformation appeared again seventy years later in David Haldane’s cartoon from 1980, but this time it was turning people into frogs.

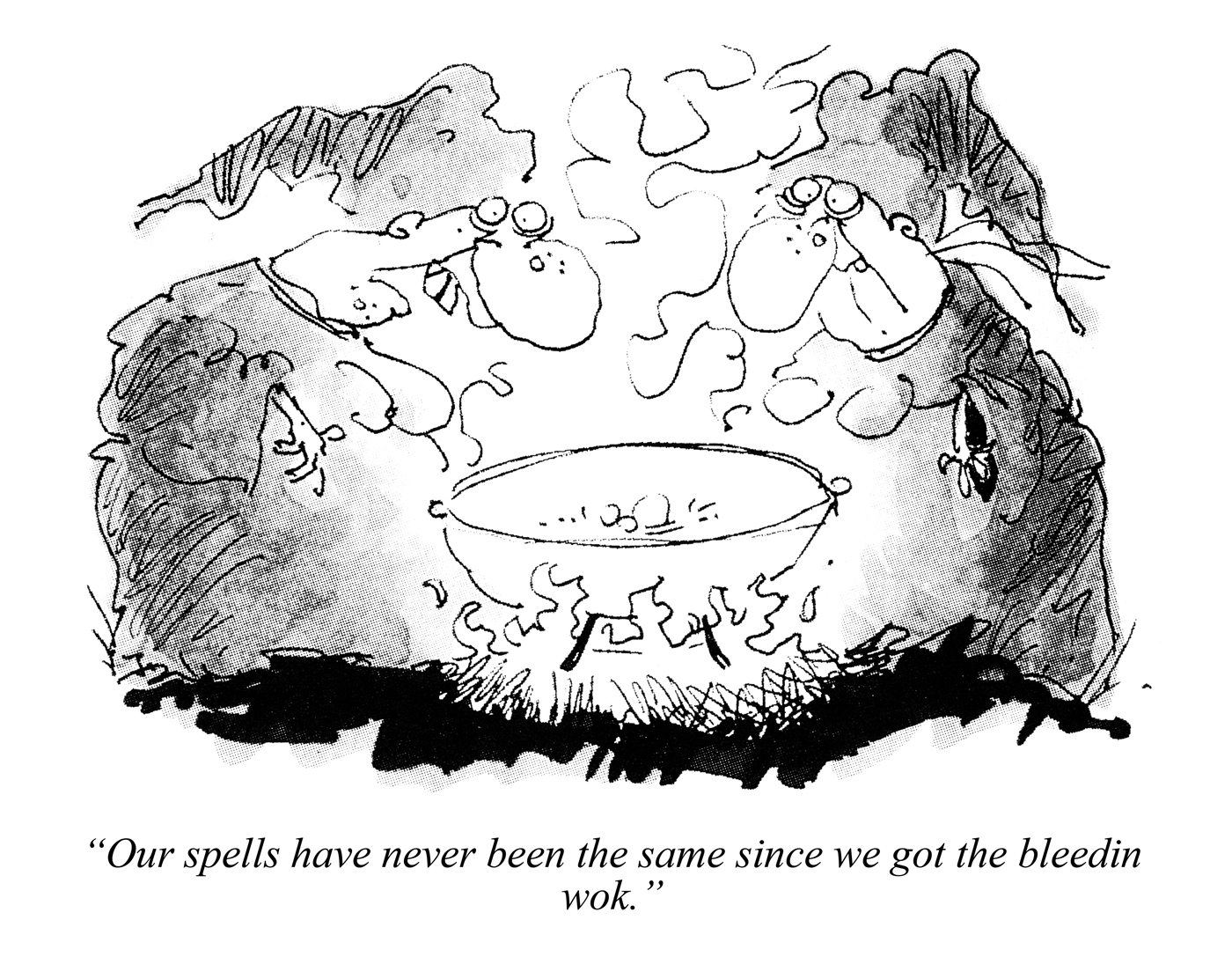

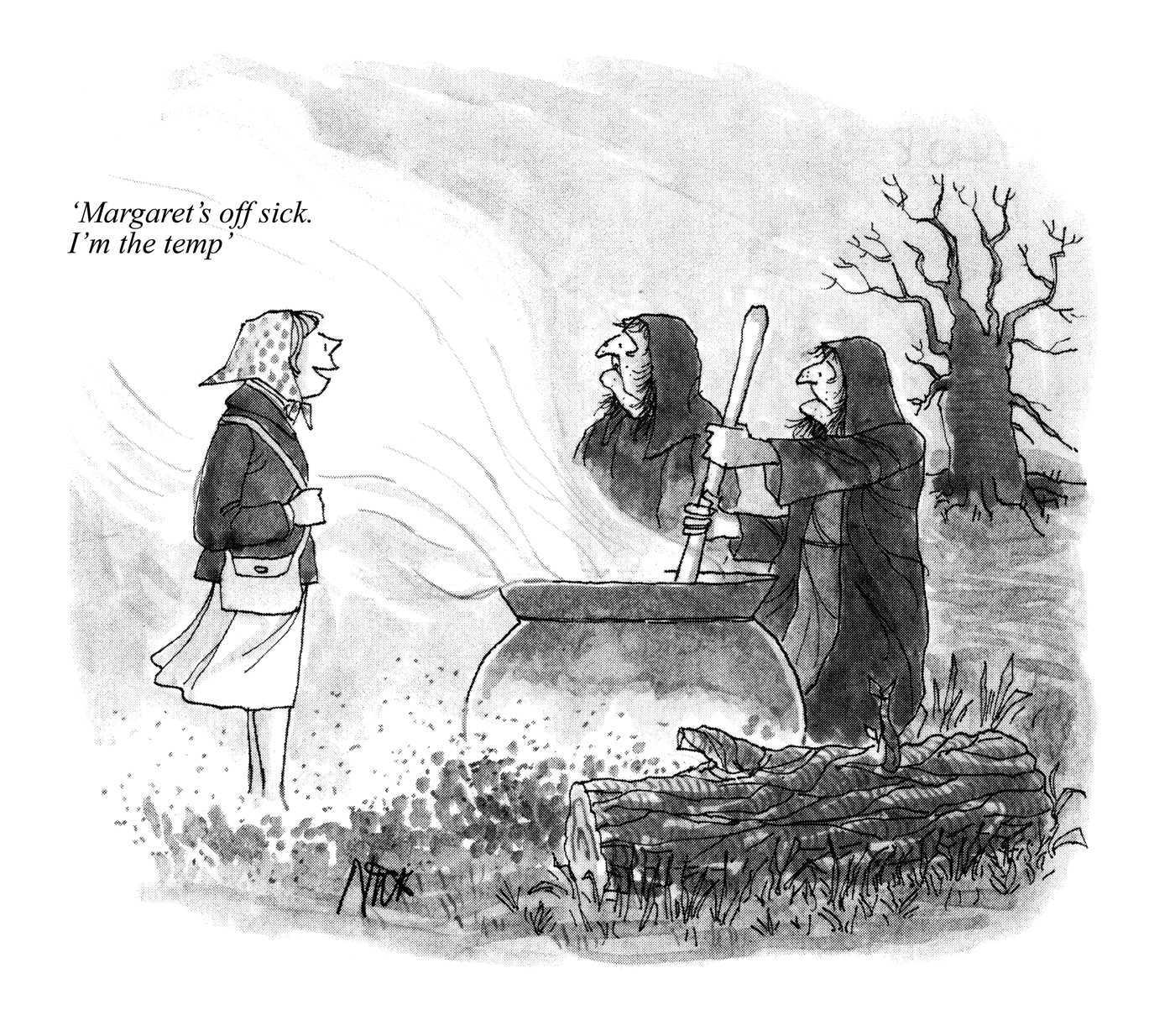

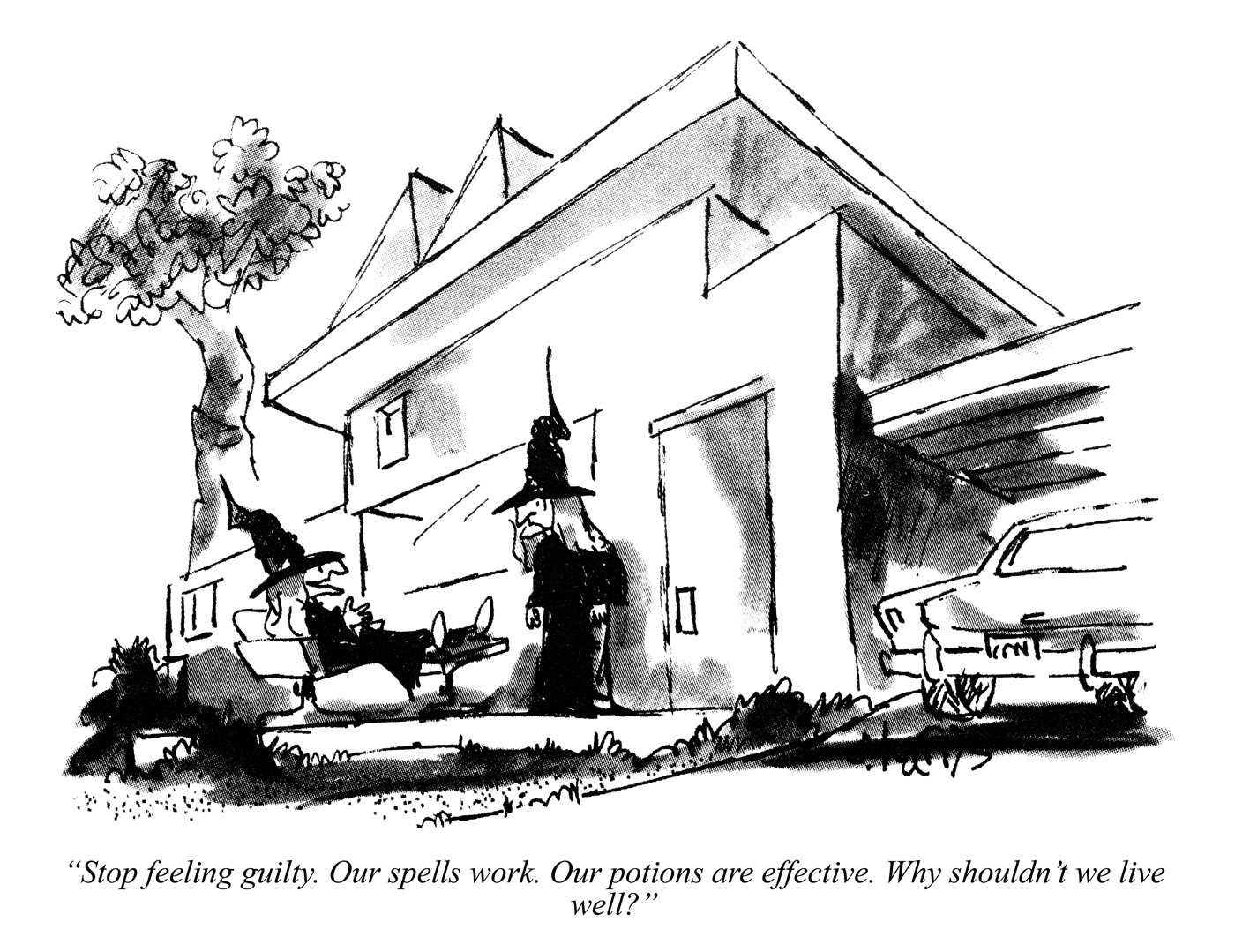

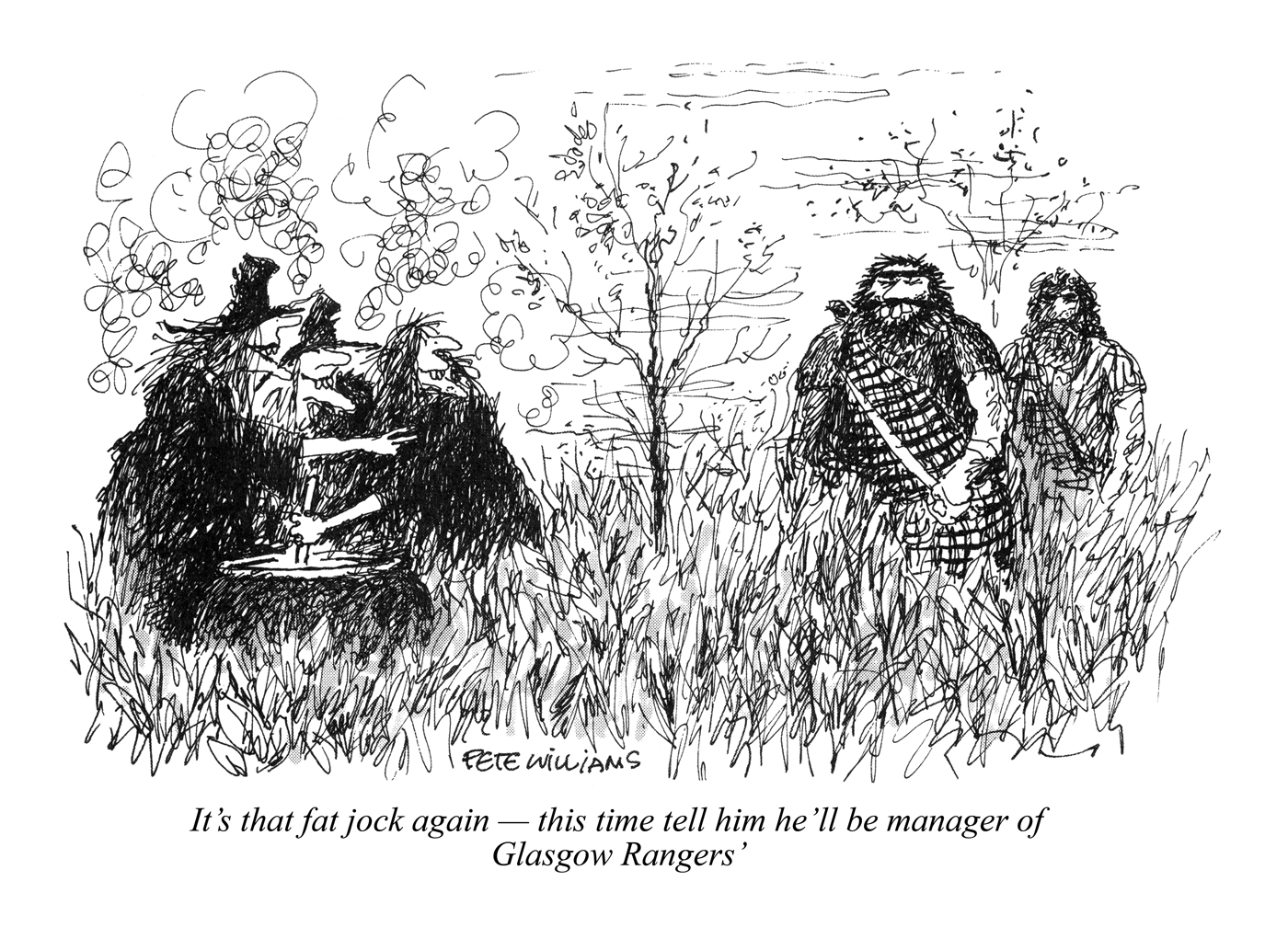

In the Eighties and Nineties cartoons featuring witches focused on their encounters with modern life and contemporary ways, from following football clubs (ffolkes), woks (Ian Jackson), aromatherapy (Richard Burnie) and temps (Nick), to feeling guilty about making money (Sidney Harris).

Yet Shakespeare’s hag-like crones stirring a cauldron was still the archetype of what a witch should look like and Pete Williams’ cartoon from July 1991 went full circle, brilliantly using the theme of Macbeth and the Three Witches’ prophesies – but bringing them right up-to-date with a reference to football.