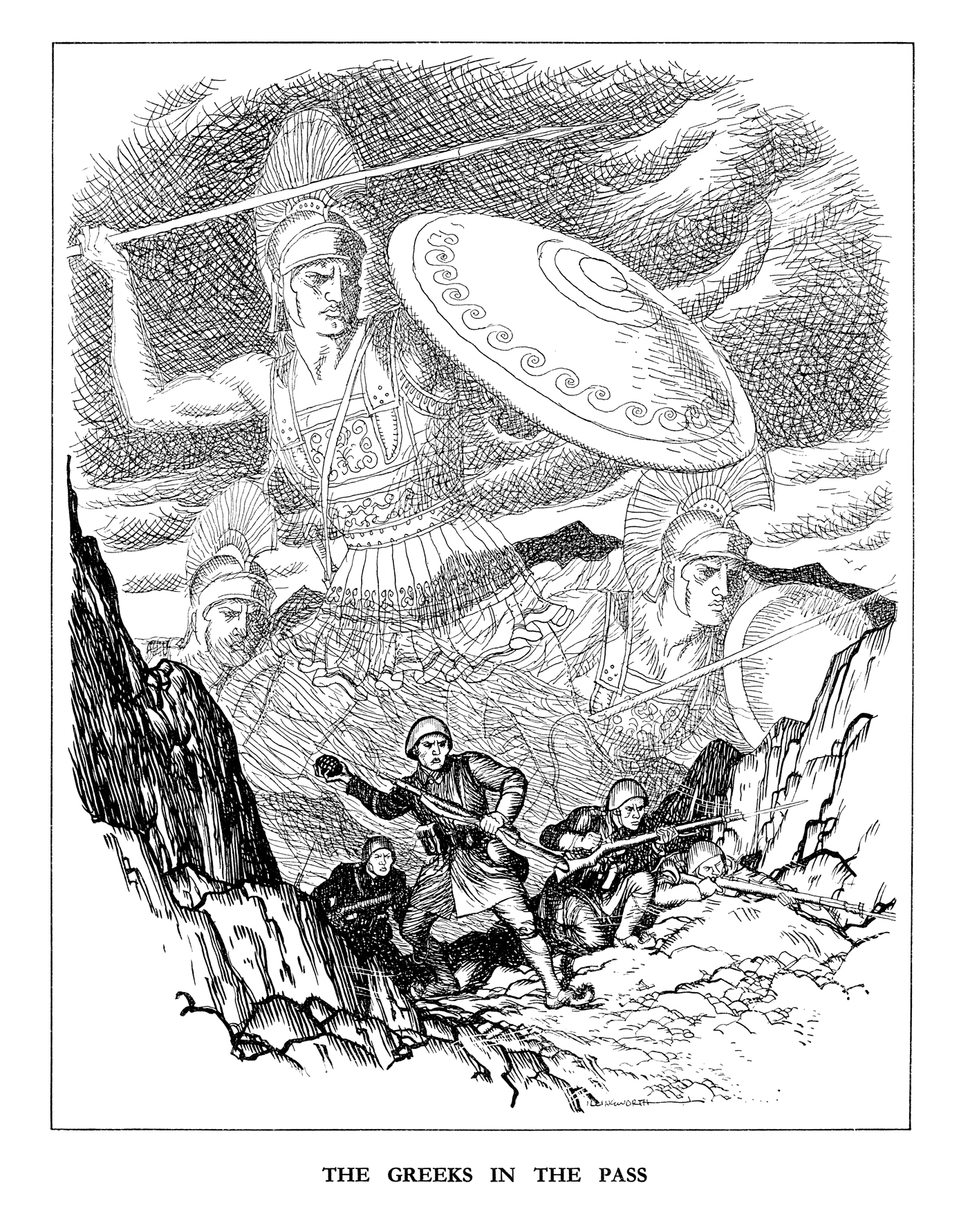

From figures of power to figures of fun, ghosts and apparitions changed dramatically in Punch cartoons over the course of two centuries.

For much of the nineteenth century following the magazine’s launch in 1841, ghosts and apparitions were a serious business. Appearing almost entirely in Punch’s influential full page political cartoons, or ‘Big Cuts’, they were potent figures – archetypes or famous characters from the past who gave warning or inspiration to those grappling with contemporary issues, targeted at the magazine’s readers and politicians alike.

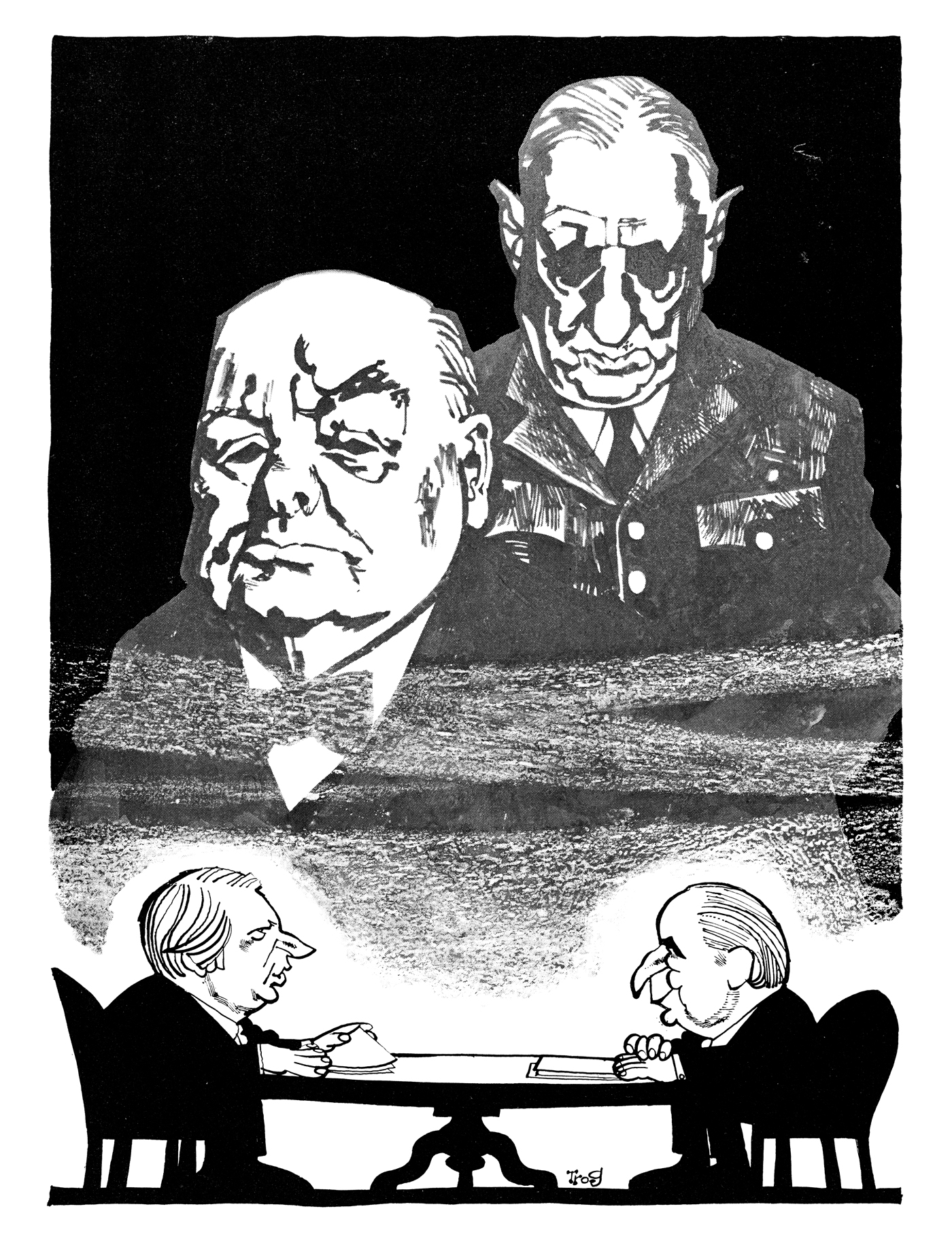

But by the end of the century and into the twentieth, ghosts began making their way into Punch’s ‘social’ or gag cartoons, where their power was defused to being simply mildly frightening and definitely humorous. The shades of the departed great, however, were still mobilised in times of turmoil and political dilemma throughout two World Wars and well into the 1970s.

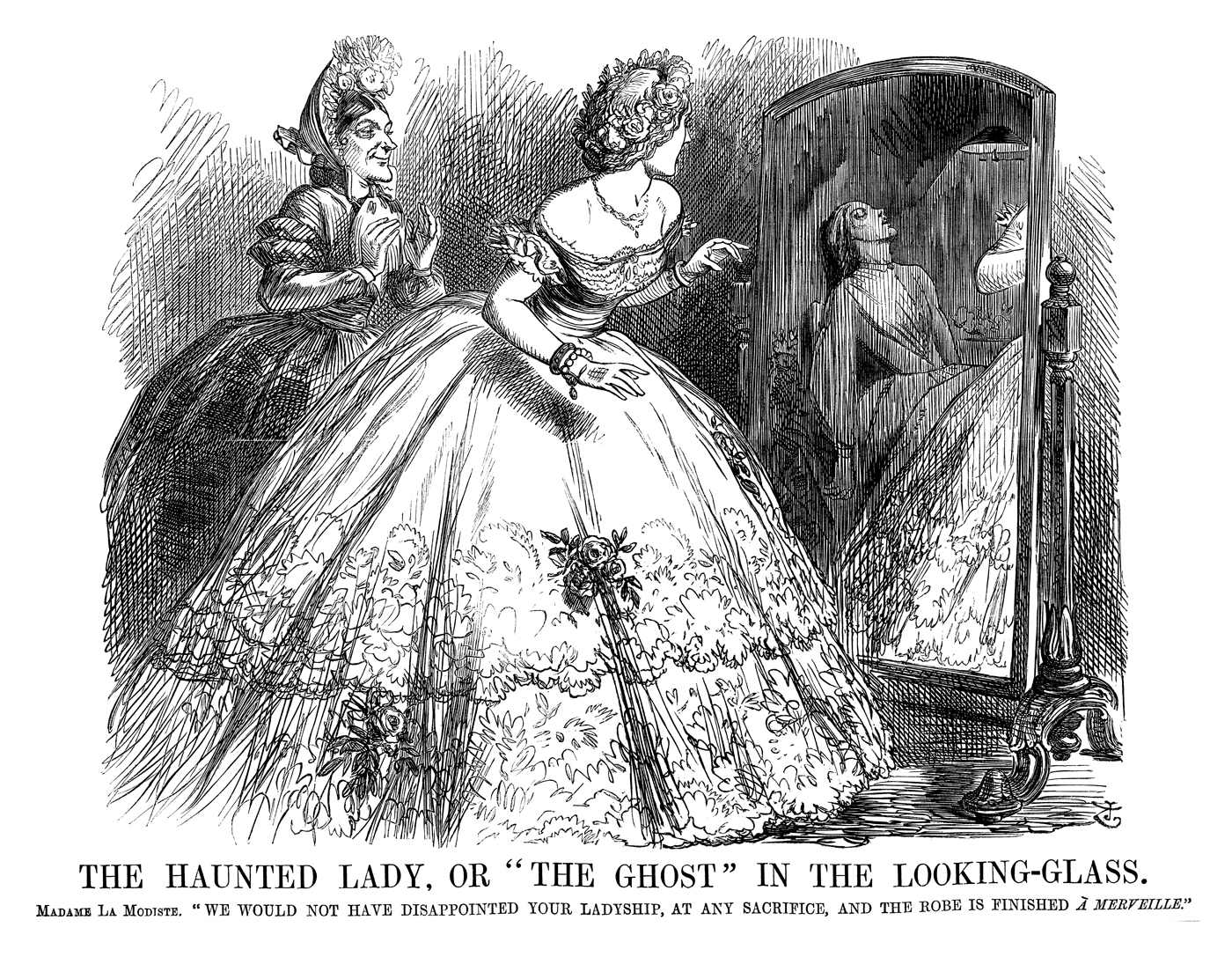

The subjects of John Tenniel’s over two thousand ‘Big Cuts’ in Punch between 1851 and 1901 were essentially the magazine’s position on what it considered the pressing social and political problems of the day. But Tenniel’s artistry and imagination – he was famously the first illustrator of Alice in Wonderland – transformed many of his cartoons into cultural reference points for decades after their first publication. Two of the most celebrated – both on social problems of the time – featured ghosts.

The Haunted Lady, or ‘The Ghost’ in the Looking-Glass from 4 July 1863 highlighted the slavery of the long working hours and appalling living conditions endured by seamstresses working for dressmakers and milliners, all to the end of dressing fashionable society women. Attended by a sycophantic modiste, her ‘ladyship’ tries on an exquisite lacy gown and, glancing to admire herself in a looking-glass, she sees not her own reflection but the ghostly apparition of the exhausted seamstress who laboured to produce her dress ‘at any sacrifice’ – even of the young worker herself.

“There floats a phantom on the slum’s foul air,

Shaping, to eyes which have the gift of seeing,

Into the Spectre of that loathly lair.

Face it–for vain is fleeing!

Red-handed, ruthless, furtive, unerect,

‘Tis murderous Crime–the Nemesis of Neglect!”

Perhaps even better known was The Nemesis of Neglect, published on 29 September 1888 in the midst of the sensation created by the ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders in East London. The cartoon was inspired by a letter to The Times from 18 September from the prolific correspondent, Sydney Godolphin Osborne, attacking the decaying and unhealthy housing suffered by the poor of London’s East End. Osborne saw these as a breeding ground for crime that all the philanthropic works by well-meaning people could not address. The bestial apparition of Crime – ‘a phantom on the slum’s foul air’ – stalking the dark alleys of East London, knife in hand, is still a powerful and terrifying image.

But by the end of the century ghosts and apparitions gradually became sources of humour. This cartoon by E T Reed from February 1890 was based on the true story of the cargo of 180,000 cat mummies shipped from Egypt to Liverpool to be auctioned off as fertiliser. In Reed’s imagination, the ghosts of the offended felines clad in their mummy wrappings, rise from an English field where they have been used as ‘fur-tiliser’, terrifying the agricultural workers spreading the rich manure.

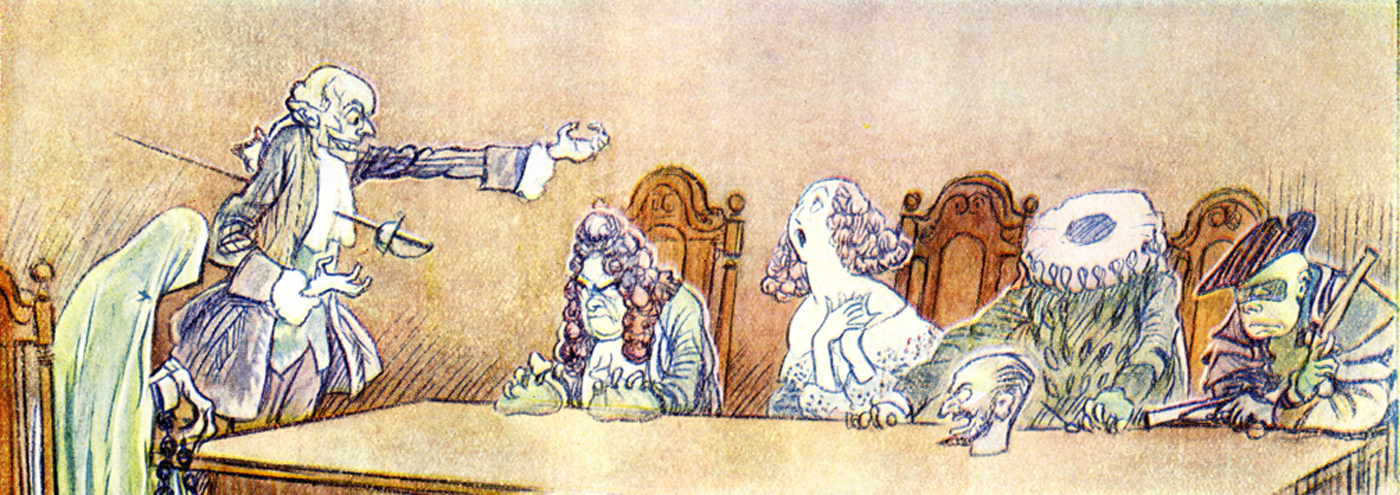

From the end of the nineteenth century until well after the Second World War the most well-trodden appearance of ghosts in Punch’s gag cartoons, however, was in the haunted house, or rather the haunted country house or castle – only aristocratic stately homes might be expected to have an interesting ghost or two!

The Plot That Failed a poem by Evoe (E V Knox) and illustrated by E H Shepard from Punch’s 1923 Almanack drew on the decline of the aristocracy after World War One and even engaged a bit of class warfare. The resident (and very upper class) ‘hereditary spooks’ of a manor house recently purchased by the Snooks, a nouveaux riches family ‘in trade’, decide to drive the unsuitable interlopers out by some vigorous haunting as the new owners gather with friends for a Christmas Eve party. But far from being terrified, the Snookses and friends find the ghostly apparitions ‘sweet’ and some inter-class mingling and a good time follows for all.

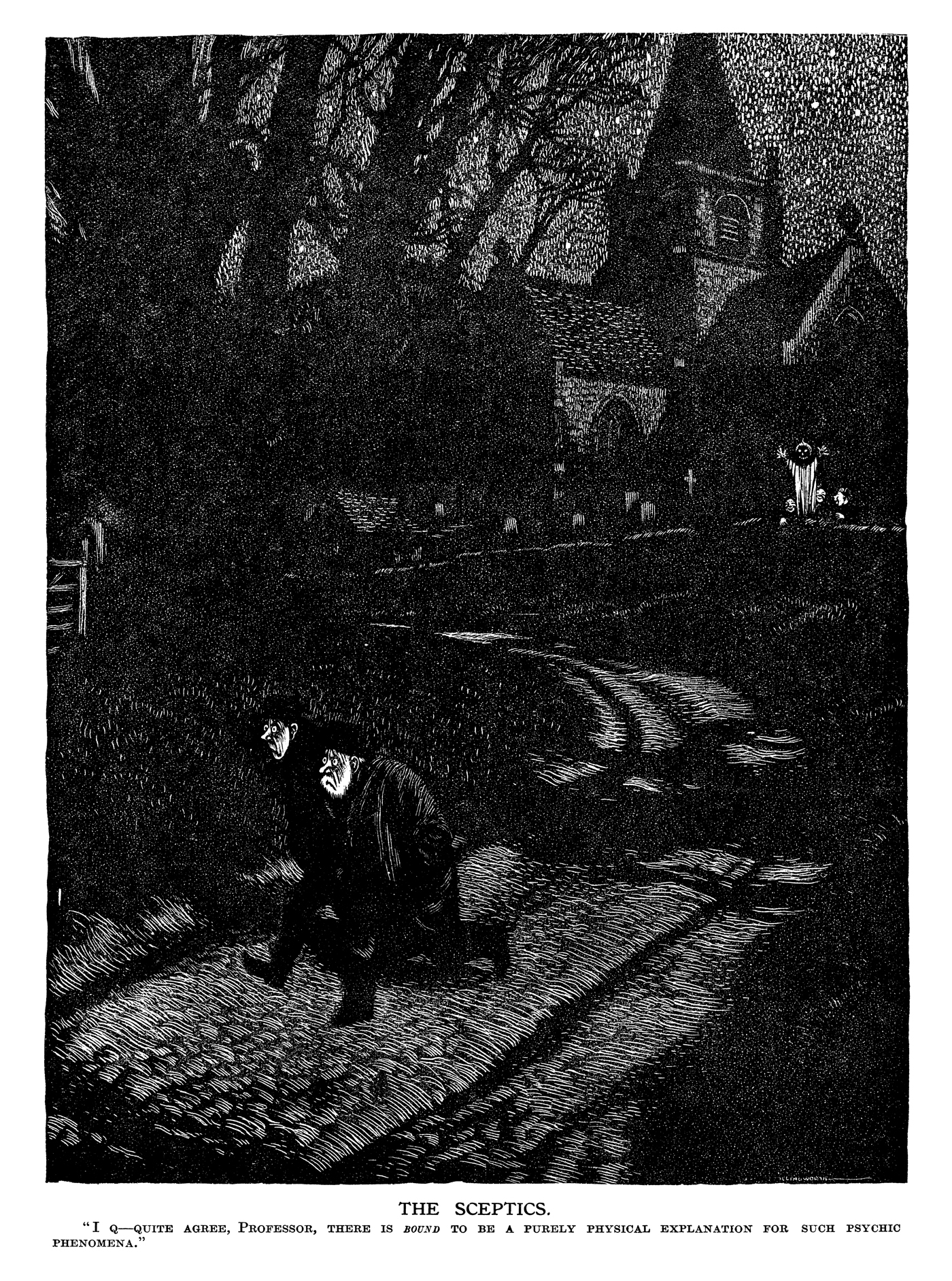

Two cartoons from Punch’s 1936 Almanack show this new take on the ghostly, as well as the growing scientific interest in psychic phenomena. In the first (by Douglas Mays), an after dinner session telling ghost stories round an open fire by guests (clad in black tie and formal dress) at a country-house weekend is interrupted by a real ghost with a story of its own. And Leslie Illingworth’s cartoon shows the evidence-led beliefs of one sceptic tested as he walks past a graveyard on a dark night.

The wonderful Rowland Emett began cartooning for Punch during WW2 while working as a draughtsman for the Air Ministry. Apart from an enduring fascination with machines and railways (the more fantastical the better), the ghostly and the supernatural frequently appeared in Emett’s cartoons. He managed to combine both in this cartoon from 1945 of some ghostly goings on in the London Underground.

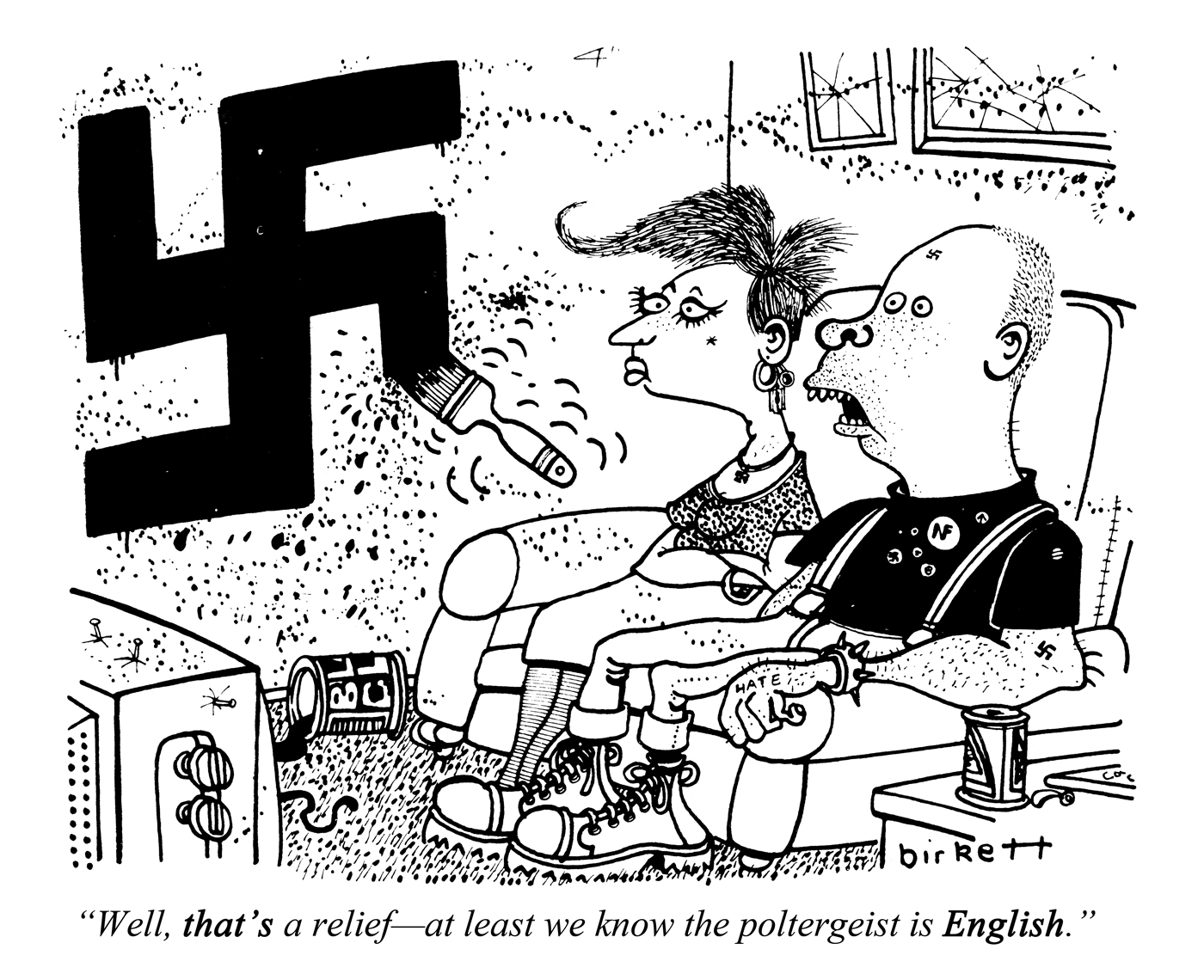

By the 1980s, like society around them, ghosts became democratised in Punch’s cartoons and moved out of stately homes and into the suburbs where various types of hauntings in the ordinary middle class semi became a favourite subject of cartoonists. Peter Birkett’s cartoon of 1983 manages to combine poltergeists, the National Front and graffiti, while the joke about Banx’s ghost in this 1984 cartoon is just how ordinary its manifestation is.

The appearances of ghosts and apparitions and how they were depicted in the pages of Punch makes a fascinating study of changing attitudes throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – as do so many of the magazine’s cartoons, which are now regarded as one of the key sources for the study of the social and political history of the time. Lots more can be found Punch’s large searchable database of cartoons at www.punch.co.uk.