Despite its elegance, like most cities Kyoto can become overwhelming. After shuffling through the crowded streets of Gion, you begin to long for the peace and solitude of the countryside. Luckily it’s not out of reach. Two stops on the JR Nara line from Kyoto central station will take you to Mount Inari, at the base of which stands the prestigious Shinto shrine Fushimi Inari-Taisha. Follow the path marked by red torii gates and enter a world outside of the city, a world of meandering paths, where there are more foxes than people.

Fushimi Inari-Taisha is an ancient shrine, founded in 711, making it one of Kyoto’s oldest and most significant places. The main shrine building stands at the foot of Mount Inari, with the iconic red torii gate-lined path winding up to the peak behind it. Before shrines were built, natural spaces where kami (Shinto deities) were believed to be present were used for worship. Mount Inari is one of these places; a shintaisan, which is the name given to a sacred mountain. Mount Inari is said to be the place where the kami Inari first descended to earth from the heavens. In Japanese mythology, Inari is the androgynous deity of rice. This may sound like a small thing to be the deity of, but in the past rice was used as a measure of wealth. Inari is therefore also associated with business and money, and many people ask them for blessings for these things. Shrines dedicated to Inari are a common sight, with there being around 30,000 of them across the whole of Japan. Fushimi Inari-Taisha in Kyoto is the flagship, and having the name ‘Taisha’ marks it as being of historic and cultural importance.

As for the foxes, in Japanese folklore the kitsune (Japanese word for ‘fox,’ but also the name given to mythical fox spirits) is one of the most notorious creatures. Somewhere over the centuries they came to be known as Inari’s messengers. At every Inari shrine you will see at least two statues of them around the entrance to the main worship hall. Usually shrines have stone lion/dog-like creatures, called komainu, to protect the kami. But at Inari shrines instead they have kitsune. At Fushimi Inari-Taisha, aside from these two guardians, as you follow the 4 kilometre trail up the mountain you will encounter hundreds of kitsune statues of all shapes, sizes, and in varying conditions of decay. The route is also strewn with sessha and massha, small auxiliary shrines with their own protective kitsune. You are never alone on the path, with all those weathered stone eyes watching you. If you walk it at night maybe you will catch a glimpse of a kitsunebi (fox fire) trail, floating amongst the tree trunks. Maybe if you follow it you will witness a mystical kitsune wedding party. Or maybe it will lead you into peril, similar to a European will o’ the wisp…

Kitsune are tricksy creatures, not to be trifled with. If you do them a favour, they will give you a sumptuous gift in return. But soon part of it will transform into dried leaves; kitsune gifts are never entirely authentic. If you spurn their existence they will change your mind. Tokutaro learns this the hard way in the Japanese folktale ‘How Tokutaro was Deluded by Foxes,’ collected in Myths and Legends of Japan by F. Hadland Davis. Skeptical about the kitsune’s magical abilities, Tokutaro agrees to a bet with his friends to spend the night on a moor where kitsune are reported to be seen. On the way there, he sees one rush past him and then immediately afterwards sees a young woman who says she is travelling to a nearby village. Tokutaro accompanies, her and when her parents are confused by her visit he convinces them she is really a kitsune in disguise. Tokutaro then tries to get her to return to her kitsune form by beating her and eventually burning her alive. A passing priest intervenes and decrees that Tokutaro shall also become a priest to repent for his crime. Tokutaro’s head is shaved… and then he wakes up alone on the moor to the sound of retreating laughter. He is left wondering whether the kitsune caused him to hallucinate his awful crime or if it actually did happen, since his head is indeed bald. Either way, he lost the bet.

The malevolent powers of the kitsune extend much further beyond head shaving and hallucinations. They are also known for possession, and bringing sickness and misfortune upon families. In his book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan Lafcadio Hearn provides a detailed insight into these kitsune legends in Izumo, a city in Shimane Prefecture on the west coast of Japan. Izumo already boasts a rich folkloric heritage, being home to Izumo-taisha which is believed to be the oldest Shinto shrine and the site of numerous events in Japanese mythology. So it is no surprise that the kitsune also have a strong presence in this area. In Izumo, kitsune are especially feared for the three evil acts they are said to cause: deceiving people with enchantments, attaching themselves to a family and causing misfortune (both for the family and the community around them), and demonically possessing people and driving them to madness. The most common shape kitsune take to ensnare humans and perform these evils is that of a beautiful young woman. If you are wise and look behind her, you might spot her tail and save yourself. Beware of lonely places, for they are most likely to be haunted by kitsune. Their bewitching fire can be extinguished by crossing your fingers to form a diamond and blowing through the shape. If someone you know falls victim to possession by a kitsune, an affliction known as kitsune-tsuki, they must be brutally beaten to drive the malevolent spirit out. If that fails, call for a priest to exorcise it. They will speak with the kitsune and persuade it to leave, usually by promising it copious amounts of aburaage (fried tofu which kitsune are rumoured to be partial to). After the spirit departs, offerings must be made immediately to the Inari shrine which it affiliates itself with to prevent its return.

Whilst cases of kitsune-tsuki can be savage, they are often quickly dealt with. For families which kitsune choose to attach themselves to things are not so straightforward. These families are called kitsune-mochi, and quickly become ostracised by their communities. Harbouring kitsune is a risky and cumbersome task. They must be fed of course, taking a large share of the family’s rice and tofu, which is a harsh setback for poor kitsune-mochi. They are rewarded for their sacrifices, but dried leaves are an insufficient substitute for a meal. If you treat the resident kitsune well, in time your family will prosper. Slight them, and ruin will soon follow. The problem is that there is no way of telling what will offend the kitsune, if indeed there even needs to be a cause – maybe one day they will simply decide to curse you with sickness or ill luck for no reason at all. When it comes to marriage, no matter how sweet-natured and beautiful a kitsune-mochi girl is no-one from Izumo will go near her. Rich kitsune-mochi have the luxury of being able to afford to find a husband from far away, where the family name and kitsune legends carry less stigma. But for poor girls, unless they can find another local kitsune-mochi to marry into then the prevalence of superstition over love often resigns them to a lifetime of solitude. As for land and property owned by kitsune-mochi, never mind if it is fertile or if the house is charming. It will never sell for what it is really worth, for fear that the new owners will too fall victim to the mercy of the kitsune.

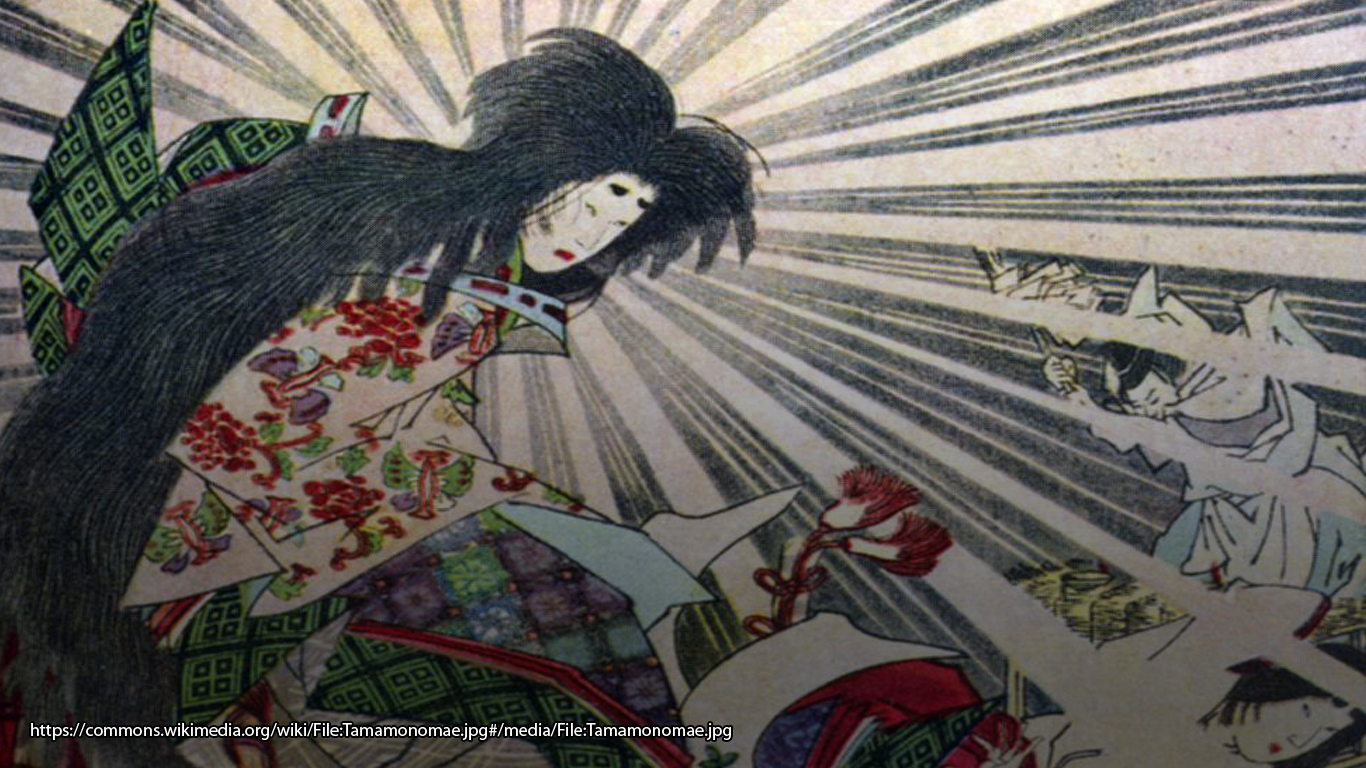

One of the most infamous kitsune was the powerful courtesan Tamamo-no-mae. Her exploits were numerous throughout Asia, but in Japan she is known for her plot to kill Emperor Toba and assume his position. Tamamo-no-mae was exceedingly beautiful, knowledgeable, and a master of every skill. She could play every instrument perfectly, write the most enchanting poems, and effortlessly partake in conversations on any topic. All in all, she was a very charming woman. Emperor Toba thought so too, and made her his consort. But soon after this, he fell gravely ill. Many doctors came to his bedside, but none could cure him. In desperation, an onmyoji (sort of shaman/spiritual healer) was called. He discerned that Tamamo-no-mae was really a kitsune, and was the cause of Emperor Toba’s affliction. To be sure, the onmyoji prepared a ritual to banish evil and Tamamo-no-mae was implored to take part in it. Reluctantly she agreed, but was unable to finish it and fled. Emperor Toba’s health instantly improved, and Tamamo-no-mae was hunted for a long time. Eventually she was found in the Nasuno Plains, an area which is now part of Tochigi Prefecture in the east of Japan. A chase ensued, finishing at a large boulder.

In some versions of the story Tamamo-no-mae uses magic to take refuge behind the boulder and remain hidden there. In others she is killed, and her spirit possesses the boulder. Either way, from that day onwards the boulder came to be known as ‘Sesshō-seki’ which means ‘killing stone.’ Any creature which ventured near it would die instantly. Even birds could not fly over it without plummeting to their deaths. Years passed, until a wandering priest named Gennō came upon the Sesshō-seki. Having been warned of its power, he performed strong purification rituals to draw out Tamamo-no-mae’s spirit. Gennō convinced her to repent all of her evil doings and released her from the stone, and she was seen no more. Free from her possession, the Sesshō-seki was no longer harmful. Gennō struck it with a hammer, and it split into hundreds of pieces which spread all over Japan. Some of the larger chunks were enshrined. The base of the Sesshō-seki can still be visited today the town of Nasu in Tochigi.

It seems that little has changed since the late 19th century when Lafcadio Hearn was writing. Even today, prospective spouses are still wary of kitsune-mochi. Offerings of tofu are still left at Inari shrines, and not everyone is convinced it is now completely safe to visit the Sesshō-seki. There are no certain explanations for where the powers and legends of the kitsune originate, which just adds to their ethereal status. So if you visit Fushimi Inari-Taisha and hike the vermillion torii gate-lined trail, remember that you are not alone. Nor are you in Kyoto any longer. You have entered the world of the kitsune. Watch out for women with tails, and floating lights. If you pause and buy a bowl of udon, don’t be surprised or offended if a slice of tofu disappears when you are not looking. Remember that centuries of folk beliefs have created the kitsune’s formidable reputation, and it’s best to respect that. Just in case.

References & Further Reading

Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan by Lafcadio Hearn (Vermont: Tuttle, 2009). Available online for free on Project Gutenberg.

Bilingual Guide to Japan: Shinto Shrine by Kato Kenji (Tokyo: Shogakukan, 2016)

Japanese Fairy Tales by Grace James (London: Senate, 1996)

Myths and Legends of Japan by F. Hadland Davis (New York: Dover, 1992). Available online for free on Project Gutenberg.

‘Tamamo no Mae’ by Matthew Meyer on Yokai.com

‘Kitsune: The Divine/Evil Fox Yokai‘ by Linda Lombardi on Tofugu