“What is the curse?”

“Lleu has been cursed by his mother so that he will never have a wife. She has cursed him harshly so that of all the races of mankind not one woman has borne or ever will bear the child who will be his bride.”

Math sucked the air between his clenched teeth.

“It is a harsh curse.”

He closed his eyes and pondered in silence.He opened his eyes and fixed them on Gwydion.

“We will make him a wife.”

He smiled

“We will make him a wife who is not of the race of mankind.”

“What must we do?”

“Fetch me flowers. Gather the yellow flowers of the broom, the green flowers of oak and the white of meadowsweet.”

Gwydion made his way out of Caer Dathyl.

He returned with his arms full of flowers. He set them down at Math’s feet.

“Now fetch me the yellow flowers of the primrose and the white flowers of apple and bean.”

Again he fetched them.

“Now gather the yellow flowers of iris and chestnut and the white of hawthorn.”

They were set on the floor.

“Now we have nine.”

Math arranged the flowers into the shape of a woman.

He knelt at her head

“You must stand at her feet.”

They raised their wands.

Math closed his eyes. He whispered words. Sweat broke from his brow. His body trembled. He gripped his wand with both hands.

He broke it.

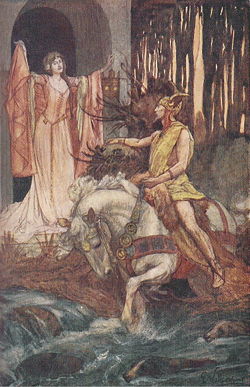

The flowers had become a woman.

Her skin was white as apple blossom, her hair as yellow as broom. She blinked. She sat up. She smiled.

“She is of the flowers,” said Math, “we will call her Blodeuedd.”

This is one episode in the extraordinary cycle of stories that are called ‘The Four Branches’ of the Mabinogion. They represent a small part of what would have been the oral repertoire of a bard in the early thirteenth century. They were set on the page by a scribe (probably a monk) and would have been copied several times before they found their way into the ‘White Book of Rhydderch’ (now in the National Library of Wales) and the ‘Red Book of Hergest’ (now in the Bodleian Library, Oxford). These two books have been dated to the late fourteenth century. They contain a hotch-potch of histories, courtly romances and archaic stories.

In the nineteenth century Lady Charlotte Guest (with a team of Welsh scholars) translated them into English. It was she who gave them the collective title The Mabinogion.

It is a title that binds together a wide range of material written by many hands over many years.

For storytellers it has been the archaic end of The Mabinogion spectrum that has been the prime source of fascination. Most of the courtly stories can be found in a more complete and satisfying form in the French versions of Chretien de Troyes. The histories are echoes of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s History of the Kings of Britain and do not easily lend themselves to re-telling. What we are left with are the extraordinary riches of the ‘Four Branches’ and the wild quest story ‘Culhwch and Olwen’. Often added to these in the storytelling repertoire is the legend of the ‘Birth of Taliesin’, a bardic relic that survived in a later manuscript attributed to Elis Gruffydd.

The challenge for storytellers is to find a way of returning these written stories to their original oral form. The texts are not easy to read. They are concise to the point of precis, in places they are over-dry, they are sprinkled with Christian overlay and a clerkish lack of vision. At the same time they carry traces of the bardic voices that would once have carried them.

It is a work of visionary reconstruction that is required, and every storyteller will bring himself or herself to the material and shape it to his or her own concerns. So that if you hear Robin Williamson, Michael Harvey, Cath Little, Daniel Morden, Katy Cawkwell or Eric Maddern telling a Mabinogion story, each will play a variation on the original material like a jazz musician riffing on a melody. That’s as it should be, and it’s also why it’s always important for a new storyteller to go back to the sources in developing a retelling.

Traditional story is primarily a language of pictures – pictures in the mind’s eye. A good storyteller sees what he is telling, and in a mysterious telepathic way, if he can see then his audience will see also. And the Mabinogion is full of pictures – Rhiannon, the queen of Dyfed, with a saddle on her back, bridled and with a bit between her teeth, carrying strangers to her husband’s hall; Bendigeidfran, the giant-king, wading across the Irish sea with his minstrels on his shoulders, surrounded by a flotilla of ships; the hanging of a mouse on a tiny gallows at the summit of Gorsedd Arberth; a dying eagle transformed into a man.

The stories are all human in their scope, they are tales of love, lust, revenge, reconciliation… most of them are about the dynamics between men and women (and there are some startling women in the Mabinogion). But at the same time it is a world where magic is always a possibility, where forms are fluid and shape-shifting a regular occurrence. There is a pervading sense of all nature being one enormous web of shared being. And it is a world that is recognizably British, populated by badger, owl, mouse, deer, starling, wild boar and salmon. Most of its landmarks can be visited. It is as close as we are likely to get to a ‘dreaming’ for the British Isles.

In my novel, The Assembly of the Severed Head, I have tried to imagine the moment in history when the ‘Four Branches’ moved from the oral form to the written. Cian Brydydd Mawr, the only bard to have survived the massacre of a Bardic School, is dying of a wound in his shoulder. He finds strength enough to recite the tales in the old way with the breath of his mouth. A devout Cistercian scribe from the scriptorium in the monastery at Aberconwy is ordered to set the stories to the page. This narrative form gave me the freedom to explore the tensions between the written and the spoken word and the differences between the two ‘voices’.

Here’s the ‘Creation of Blodeuedd’ as it is written in the text (Lady Charlotte Guest’s translation).

“Well,” said Math, “we will seek, I and thou, by charms and illusion, to form a wife for him out of flowers.”

So they took the blossoms of the oak, and the blossoms of the broom, and the blossoms of the meadow-sweet, and produced from them a maiden, the fairest and most graceful that man ever saw. And they baptized her, and gave her the name of Blodeuedd.

For my version of this episode, with which I started this article, I went to a bardic poem, ‘The Battle of the Trees’, and filled the story out with a mixture of research and license. That is the storyteller’s prerogative.

Albert Lord, in his seminal book on the oral tradition, The Singer of Tales, has written:

‘An oral poem is not composed for but inperformance…. Singer, performer, composer, and poet are one, under different aspects but at the same time. It is sometimes difficult for us to realize that the man who is sitting before us singing an epic song is not a mere carrier of the tradition but a creative artist making the tradition… But there is another world, of those who can read and write, of those who come to think of the written text not as the recording of a moment of the tradition but as the song. This becomes the difference between the oral way of thought and the written way.’

Win a copy of The Assembly of the Severed Head by Hugh Lupton

The renowned storyteller Hugh Lupton has offered a copy of his fantastic novel, The Assembly of the Severed Head: A Novel of the Mabinogi, for one lucky #FolkloreThursday newsletter subscriber this month!

‘A small monastic outpost in 13th Century Wales is rocked to its core when a gruesome discovery is made on the nearby shoreline: a severed human head. It’s the first of several to wash up along the surrounding coast, and not long after, the holy brothers stumble across the smouldering ruins of a bardic school with a pile of decapitated bodies inside. Only one survivor, barely alive, is found hiding nearby. He is Cian Brydydd Mawr, the greatest bard of his age, who holds in his head the four `branches’ of an ancient, epic Welsh myth cycle: The Mabinogion. Physically weak but strong willed, he asks the monks to put aside their rigid Christian doctrine and commit his oral tales to parchment – before the stories of spirits and shape-shifters, giants and time-travellers, curses and spells, are lost forever…’

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid September 2018; UK & ROI only).

The book can be purchased here.