Many years ago, when I was a student at Cambridge University, a group of my friends once claimed to have called up a spirit during a weekend at a Tudor country house. On their return to Cambridge they found themselves beset by paranormal phenomena. After a few days they agreed to meet together exorcize the spirit. Accordingly, one morning they gathered in the chapel of a Cambridge college; one of the students took hold of the cross on the altar, pressed it to his forehead, and willed the spirit to depart. According to my friends, the ritual seemed to work.

None of my friends knew much about exorcism, but the idea of performing a ritual to rid themselves of an unwanted spiritual influence seemed the right thing to do, as it has to people throughout the world for millennia. Exorcism can be defined as the attempt to cast an unwanted spiritual entity out of the body of a human being, or (in a broader sense), the casting out of unwanted spiritual entities from places. The practice can be found across many cultures and many religions. In Christianity, however, exorcism is much more than just a religious practice; on closer inspection, it turns out that the beliefs and practices of exorcists owe more to folklore than they do to religious dogma. The official doctrine underpinning exorcism in the Roman Catholic church, for example, is quite slim – it is simply the belief that the Devil and demons exist and can take control of human beings. The Bible, similarly, provides little detail about possession and exorcism. Many Christian exorcists therefore add beliefs taken from folklore to their demonology – speaking, for example, of ‘ancestral spirits’ passed from generation to generation; portraying demons as physical entities that have to exit via bodily orifices; using violence against the supposedly possessed person to drive the demon out; and claiming that possession is caused by curses and witchcraft.

The uneasy coexistence of religious doctrine and folklore in exorcism is nothing new; nor is it just the result of missionary encounters between Christianity and animist cultures in Africa and elsewhere. In England, visitors to medieval churches are often told that the font is located next to the church’s north door so that the Devil could exit after being exorcized from children about to be baptized. It is quite true that, as part of the rite of baptism, the priest commands Satan to leave the child about to be baptized. However, the church never officially interpreted this as a literal casting out of Satan; the rite was a relic of a time when pagan adults were baptized into the church and an exorcism was added just in case one of them was possessed. However, even though the church never advocated the idea that newborn babies are possessed by Satan, it stuck in folklore, and the unwitting alliance of unbaptized babies with Satan made them vulnerable to the fairies. It was believed throughout England that if a baby failed to cry at his or her christening, the Devil had not really gone. Furthermore, the north is associated with Satan in both Jewish and Christian legend, so this may have given rise to the legend about the north doors of churches; the real reason for the location is that fonts are sited close to the entrance of the church because baptism is the entrance to the Christian life.

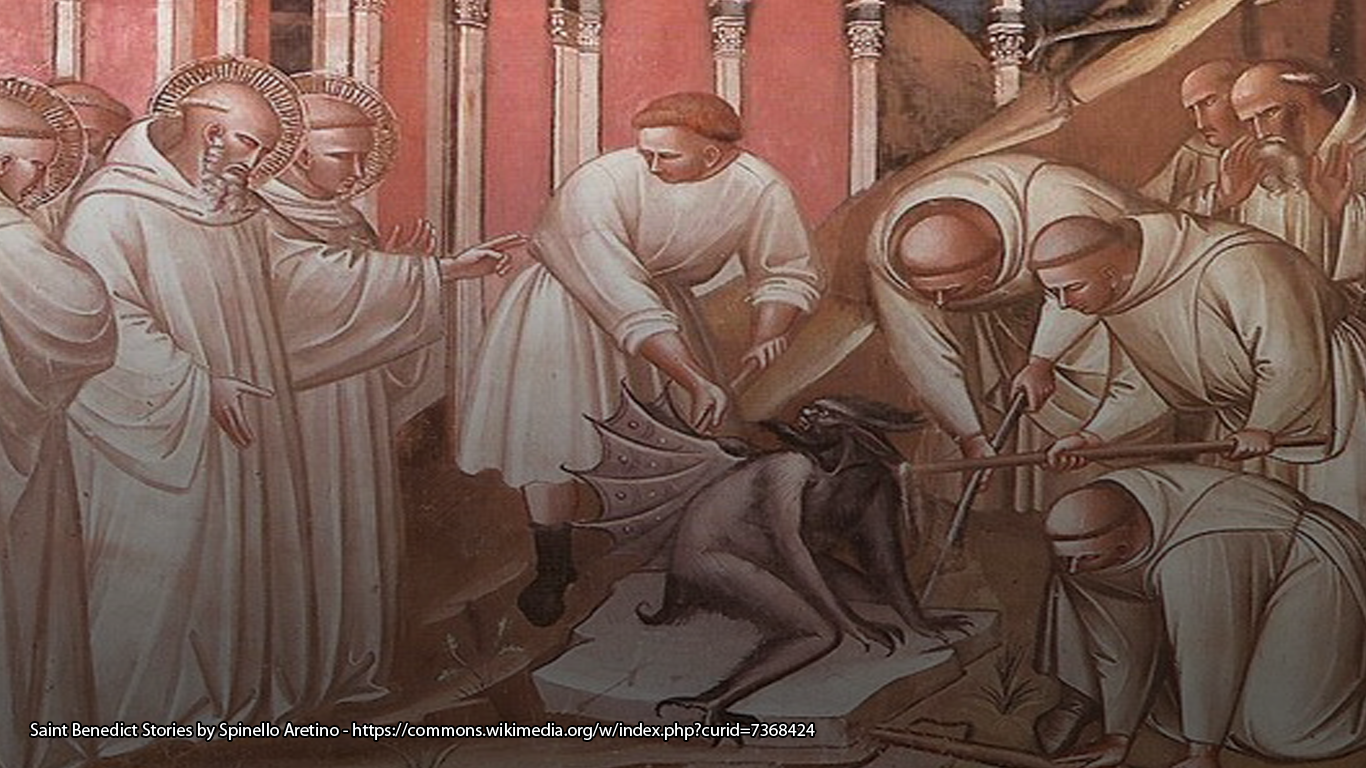

Exorcism of possessed people by priests reciting a specific rite, of the kind made famous by The Exorcist, was a comparatively rare practice until the sixteenth century. It was virtually unknown in medieval England. Instead, people who believed themselves to be possessed made pilgrimages to the shrines of ‘exorcist saints’, such as St Bartholomew’s Hospital in Smithfield and the tomb of King Henry VI at St George’s Chapel in Windsor. One especially popular ‘exorcist saint’ was Sir John Schorne, a thirteenth-century rector of North Marston, Buckinghamshire, who was never canonized but was nevertheless venerated as a ‘folk saint’ throughout England. Schorne was often portrayed on rood screens dressed as a doctor of divinity, sometimes wearing spectacles, and always holding a boot containing the Devil. This was because Schorne was said to have confined the Devil to a boot by his prayers. Another celebrated English ‘exorcist saint’ was St Dunstan, a tenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury who, according to later legend, was said to have pinched the Devil on the nose with a pair of tongs when he was working as a blacksmith earlier in his life.

The legends associated with John Schorne and St Dunstan are typical of English folklore about exorcists. No English folk tale features the exorcism of a person possessed by the Devil, but tales about the exorcism of places and the humiliation of the Devil by powerful clergymen form a distinct category of English folklore and are found in most counties. The word ‘exorcism’ is not always used in such folklore; instead, many tales collected by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century folklorists describe a group of clergymen (usually seven, nine or twelve) ‘praying against’, ‘reading down’ or ‘laying’ a spirit (either a demon or a ghost) who was haunting a place. The ‘reading down’ either forces the spirit to depart somewhere else (usually the Red Sea) or confines it in a small container like a boot or bottle (a trope almost certainly inspired by the medieval legend of John Schorne). The container is then put somewhere where it cannot be retrieved, such as a river or a deep lake or pond. Often such tales are associated with named legendary clergymen who were considered to be especially powerful exorcists because they had attended the University of Oxford and mastered exotic languages such as Greek, Arabic and Syriac. Some of the clergymen in these tales, such as John Ruddle of Launceston, actually existed.

There is no direct evidence that these ‘reading down’ ceremonies ever actually took place, although rural clergy undoubtedly offered reassurance (and sometimes more than reassurance) to their parishioners about unquiet spirits. By the seventeenth century, the idea of demonic possession had become thoroughly confused and conflated with bewitchment, so exorcism became entangled with witchcraft beliefs. Occasionally, accused witches would even be asked to exorcize the person they had allegedly bewitched. For complex political reasons, exorcism of persons was almost completely banned in England in 1604, but there was no ban on exorcizing ghosts from places. Furthermore, some clergy dealt with the Devil by excommunicating him with bell, book and candle. This might seem bizarre (given that the Devil is presumably not a communicant member of the church), but the practice was grounded in early Christian liturgies that speak of ‘excommunicating’ the Devil. Furthermore, the 1604 ban only applied to the clergy; it did not stop laypeople trying to exorcize the Devil, and local ‘cunning-folk’ quickly cornered the market for exorcism once the church gave up the practice.

Most of the old-style ‘exorcist parsons’ had died out by the early nineteenth century, but exorcism made a dramatic comeback in England in the 1970s. Even before The Exorcist hit cinema screens in 1974, many bishops in the Church of England had already started appointing diocesan exorcists, fearful of the apparent ‘occult revival’. Today, every diocese in the Church of England is supposed to have a ‘deliverance advisor’ whose job is to perform exorcisms. The Roman Catholic church in England and Wales has many fewer exorcists, but those there are have been trained in Rome by the International Association of Exorcists. In some free churches, especially those in the Pentecostal tradition, exorcisms are almost a weekly event. Contemporary exorcisms continue to be informed not just by religious doctrine but also by culturally specific expectations; in Britain and America, those expectations are often set by cinematic portrayals of what exorcism should involve. Alongside religious doctrine, modern folklore therefore remains central to people’s perceptions of possession and exorcism.