Harvest is the most important time of the agricultural calendar; the fortunes of farms, families, and even entire communities are tied to its outcome. Unsurprisingly, harvest has developed its own array of deities, traditions, and superstitions to safeguard its success, which are found in almost every farming culture worldwide.

Ever since the first farmers planted their crops over 10,000 years ago, they have had an anxious wait for summer. Will there be enough hot weather to ripen the corn? Will an unlucky wet spell rot the grain in the ears? Will the yield feed the community for the coming year or allow the farmer to pay his rent? If not, it will be another year before the next opportunity comes.

Until modern machinery redefined agriculture, corn was harvested by hand using sickles or scythes which systematically cut through the stems and laid it in swathes for binding. The action was difficult to master: if done incorrectly the stems would simply be knocked flat. Reaping gangs toured the local farms, and their leader, known as the Lord of the Harvest – the most skilled man present – arranged the scheme of work and the men’s pay. The Lord opened the field and set the pace. Each man was expected to reap an acre a day, working in a line or ‘flight’ across the field.

The reapers were followed by women and boys who bound the corn into sheaves, ingeniously tied with wisps of straw. A good binder could tie for three reapers. The sheaves were then stood in pairs or ‘shocked’ (pronounced ‘shook’) to dry for several days before the ‘shocks’ or ‘stooks’ were taken to the barns.

The corn has to be cut as soon as it is ripe, or else the quality deteriorates and the grains shed from the ears, but it must also be dry else it will quickly spoil. A prolonged wet spell at the critical time could – and still can – cost an entire harvest. While the weather held, every able-bodied man, woman and child would be out in the fields. This is the reason for the six-week British school summer holiday today. Harvest has always provided a time of bonding between communities as everyone slogged together under broiling sun, glowering clouds, and driving rain to bring the harvest home.

On fine days, work could begin at 4am and continue well into the night. The Harvest Moon; the full moon falling closest to the Autumn equinox, rises unusually close to sunset and is so named because it provided harvesters with valuable extra light.

Children were employed in gleaning or leasing: picking up the stray ears of corn from the stubble. This was exhausting work involving hours bent double in the sun. The barley and beans went to the farmers for animal feed; wheat was kept by the gleaners and provided a vital part of the diet of poorer families.

Homemade cider, ‘sharp enough to cut the throat of a graveyard ghost’, was an expected perk and was included in harvest contracts. It was brought out to the fields at regular intervals during the day. A gallon [eight pints] was the standard daily allowance per man, although they could always have more if they needed it. Harvest teas are a tradition still maintained on some farms. The harvesters couldn’t be allowed home for tea, losing valuable time, so the farmers’ wives took lavish hampers of sandwiches, cold pies, and cakes to the fields for the workers.

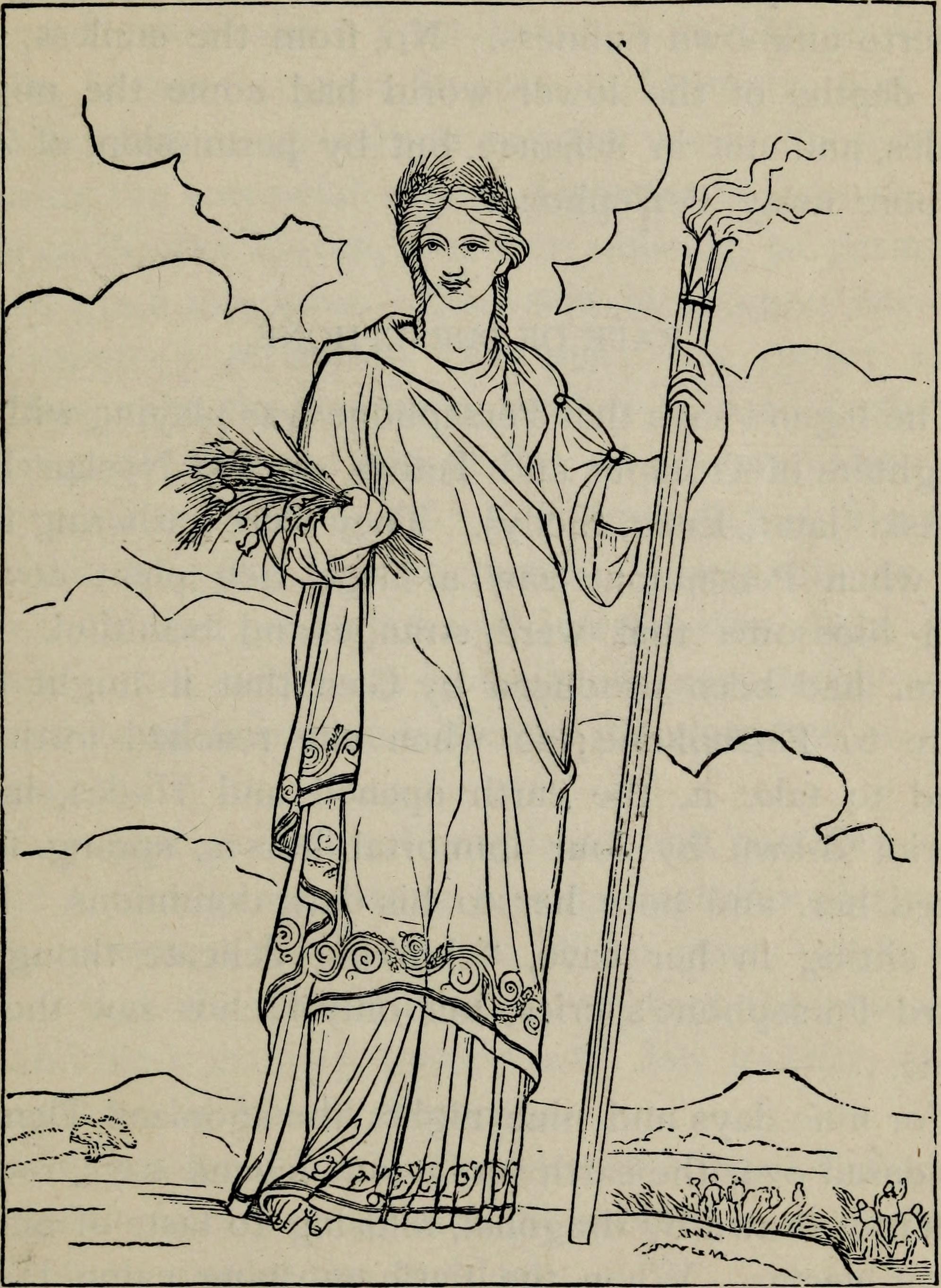

The last sheaf of corn was always saved. This was believed to contain the corn spirit, which was gradually condensed as harvest progressed until it reached the final sheaf to be cut. Often the sheaf was scattered on the fields in spring, returning the spirit to the fields. In some areas it was hung up for the hungry birds to peck on New Year’s Day; in others it was made into a corn dolly. This tradition exists across Europe and it is believed by many in the pagan tradition that this is a relic of the millennia-old belief in the Dying-and-Rising God or God of the Green, who dies in Autumn to be reborn the following Spring.

The Harvest Home, when the last wagon was on its way to the barn, was the culmination of harvest. The horse and wagon were bedecked with flowers and ribbons, and everyone crammed on top to sing Harvest Home songs. Examples from Warwickshire include:

Up! Up! Up! A happy harvest home!

We have sowed, we have mowed,

We have carried our last load!I’ve ripped my shirt and teared my skin,

To get my master’s harvest in!

The wagon was met with ale and cakes and a Harvest Home supper was provided by the grateful farmer. Everyone crammed into the barn for boiled beef, bread, cheese, plum pudding, and the obligatory vast quantities of cider. Singing and dancing continued long into the night.

In the 1870s, harvest changed forever when the horse-drawn reaper-binder appeared. Two men could now cut and bind an acre of corn an hour. The harvest gangs were no longer needed, although the sheaves still had to be shooked, pitched into wagons and unloaded in the barns, and gleaners were still vital.

The tractor-drawn reaper-binder followed, then in the 1930s came the combine harvester which also threshed the grain from the ears, leaving the straw in the fields. What was once a community effort now involved only a handful of farmworkers.

But there is still something magical about harvest, for farmers and non-farmers alike. There is something fascinating about a combine harvester rumbling across a field amidst a billowing dust cloud. The time which once made or broke communities, inspired prophets, defined religions, and ultimately made us who we are, still triggers something of its former magic, deep within our unconscious minds.

Win a copy of The Wolf of Allendale by Hannah Spencer!

We have an eBook** copy of Hannah’s spooky folk horror novel for one lucky #FolkloreThursday newsletter subscriber this month!

‘The fates of two wise men from the same village living in different time periods are connected by one mythical creature—and forces they cannot control—in this compelling supernatural tale that imaginatively retells the historical legend of the Wolf of Allendale.

In a Druid village in Northumberland, England, Bran, the village leader, must face two dangerous opponents: an otherworldly animal and formidable invaders from the south.

Two thousand years later, at the dawn of the Industrial Age, this sleepy English village once again faces the frightening menace. Something is killing the sheep—and leaving large, mysterious footprints across the countryside.

In this thought-provoking paranormal novel, Hannah Spencer uses the story of the Wolf of Allendale as a creative lens to examine the clash of progress and tradition as she brings to light ancient folklore that is nearly forgotten.’

Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid September 2017; UK & ROI only).

** The winner will need to download the BookShout app to receive their copy.

The book can be purchased here.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Roy Palmer (1976) The Folklore of Warwickshire. B.T. Batsford Ltd.

J. Harvey Bloom (1930) Folklore in Shakespeare Land. Mitchell Hughes and Clarke.

George Ewart Evans (1969) The Farm and the Village. Faber.

Roy Palmer (1994) The Folklore of Gloucestershire. Westcountry Books.