What’s in a curse? A lot more than just the wave of a wand from an evil fairy godmother. For many residents of ancient Britain, it involved invoking a god to influence a particular individual according to their wishes; they often expressed these desires on tiny leaden documents in a format common throughout the Greco-Roman world: the curse tablet. Representing a concept likely imported as a result of foreign invasion, trade, and settlement, the 130 curse tablets in Bath, England, demonstrate a fascinating process of cultural hybridization.

What was so special about Bath, or “Aquae Sulis” in Latin? It was a place for individuals to “take the waters,” to soak in the healing properties of its mineral-rich springs. But Bath was a cult site for the worship of the goddess Sulis Minerva, a mistress of healing and justice. Herself likely a product of interpretatio romana, which conflated pre-existing divinities with their Roman equivalents, Sulis Minerva ruled over the powerful waters at Bath. But how did supplicants reach her?

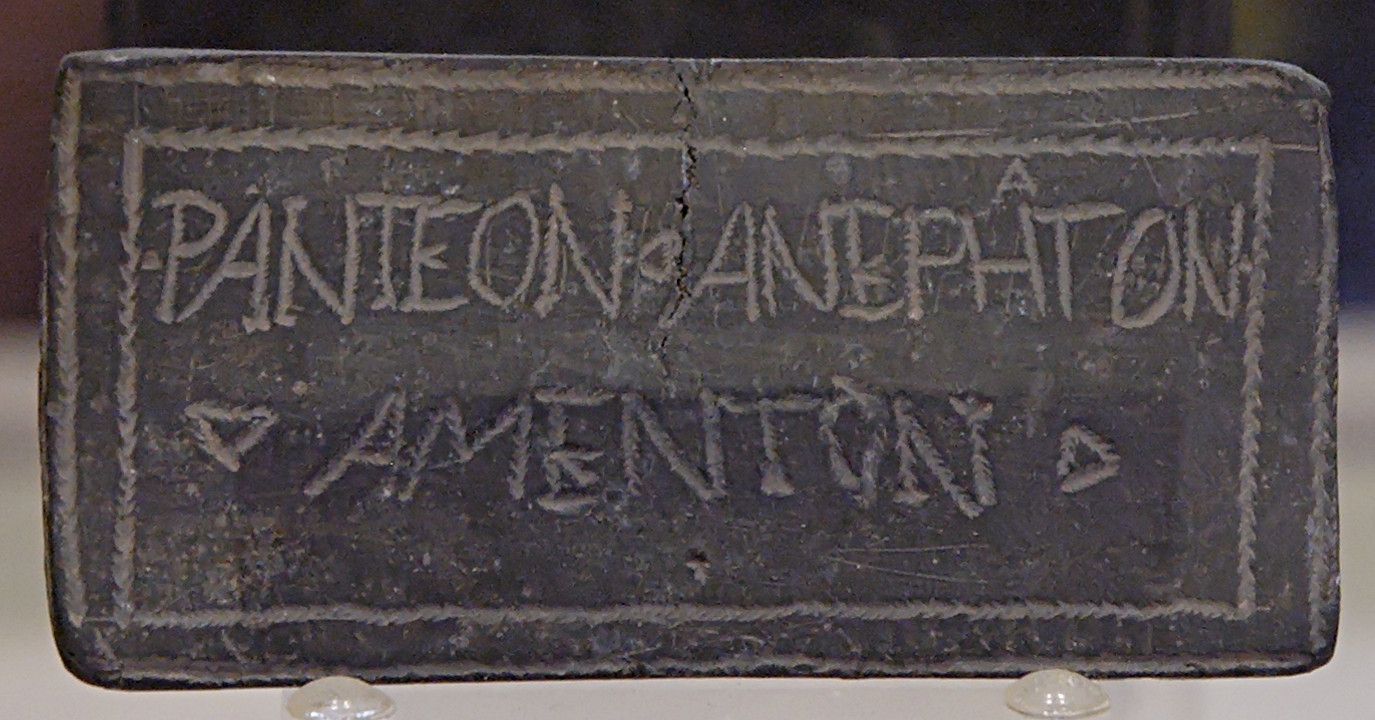

Prayer was one way to get in touch with the goddess, but, if a worshipper had a distinct problem, one might request aid from Sulis Minerva on a curse tablet. Since most were probably illiterate and couldn’t write in miniscule script, he or she would visit a scribe; on a piece of lead or pewter, the scribe would write a request for Sulis Minerva or another god on to avenge the wrong done to their client, to punish the one who perpetrated the crime, and, if something was stolen, for the goods to be returned to their rightful owner.

Most of the curse tablets found in Bath and Uley, a religious center located only 27 miles from Bath, involve stolen items. Supplicants ask different deities to both send back their goods (or, in one case, possibly a slave girl) and to punish the culprits. In return for the god’s help, the devotees would promise the divine one a gift, perhaps even the stolen item if it was returned to them. Sulis Minerva was often the goddess of choice because she was the goddess who oversaw the places—her baths and sanctuary— where their goods were taken. By throwing the curse tablets down into the murky depths of Sulis Minerva’s sacred springs, the supplicants attempted to send them directly to her. It’s also possible that the tablets were displayed publicly, their curses recited to enact the spells therein, then cast into the sacred spring. Or they were set up, then, when the sanctuary got too crowded, brushed off into the waters.

“curse him who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether man or woman, whether slave or free …”

The relationship between man and god was a contract; in exchange for the divine powers delivering justice, the devotee would provide the god with an offering or sacrifice. In order to help the invoked god track down the guilty party without any restrictions, the petitioner tried to mention every possible type of individual the villain could be. For example, one Docilianus asked “the most holy goddess Sulis” to “curse him who has stolen my hooded cloak, whether man or woman, whether slave or free …” While many other types of magic appeared in defixiones from elsewhere in the empire, those found in Britain almost exclusively dealt with theft. Most of the tablets found at Bath involve theft, but few of the many found outside Britain discuss it. Thus, it appears that the curse tablets from Bath demonstrate a unique type of cultural hybridization, combining concerns of those who resided in Roman Britain with a Greco-Roman form of magical supplication and its corresponding language.

But why were the Brits so concerned with theft? In a remote province without a heavy police presence, individuals visiting the baths or temples would have to have been had money in order to afford guards or slaves to protect their belongings while they soaked or prayed. This appears to have been the problem at Bath, though bathhouse thieves were an all-too-common phenomenon across the Roman Empire.

“Docimedis has lost two gloves. (He asks) that (the person) who stole them lose his mind and his eyes in the temple where (she) appoints.”

The items reported stolen in the tablets were those that would have been stowed away when one went to bathe: cloaks, coins, et cetera. For example, one Docimedis pleads to Sulis Minerva: “Docimedis has lost two gloves. (He asks) that (the person) who stole them lose his mind and his eyes in the temple where (she) appoints.” Solinus goes even further in his request: “Solinus to the goddess Sulis Minerva. I give to your divinity and majesty my bathing tunic and cloak. Do not allow sleep or health to him who has done me wrong, whether man or woman, whether slave or free, unless he reveals himself and brings these goods to your temple.”

As a result, scholars have concluded that many of the supplicants may have been poor or of a relatively low social status. Since they couldn’t afford guards, they would find their possessions stolen upon returning to their cubbies in the baths; since there was probably little local law enforcement available to Britons, they would appeal to a higher power: a god. But, since most provinces were probably under-policed, why did the Brits seem obsessed with burglary? Perhaps that was just a coincidence of the archaeological record; after all, curse tablets would have been a relatively cheap and accessible means of requesting vengeance throughout the Roman world.

The term defixiones refers to a type of binding magic, a spell used to restrain a competitor. In contrast, the Bath curse tablets largely fall under the category of “prayer for justice,” or “pleas addressed to a god or gods to punish a (mostly unknown) person who has wronged the author (by theft, slander, false accusations or magical action), often with the additional request to redress the harm suffered by the author,” as defined by Henk Versnel.

A fascinating site in and of itself, Bath, along with the curse tablets found there, represents an interesting kind of cultural hybridization. Visitors to Sulis Minerva’s sacred springs used a Greco-Roman magical ritual, complete with legalese and religious contracts, to express their unique day-to-day concerns. After all, who better to ask for help in the baths than the goddess of Bath?

References

Adams, Geoff W. “The Social and Cultural Implications of Curse Tablets [Defixiones] in Britain and on the Continent.” Studia Humanoria Tartuensia 7A, no 5. (2006):8-10.

Cousins, Eleri H. “Votive Objects and Ritual Practice at the King’s Spring at Bath.” TRAC 2013: Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, London 2013. Ed. Hannah Platts, Caroline Barron, Jason Lundock, John Pearce, and Justin Yoo. Philadelphia, PA: Oxbow, 2014. 52-64.

Cunliffe, Barry, and Peter Davenport, eds. The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath: The Site. Volume 1 of the Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath. Oxford: OUCA, 1985.

—. The Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath: The Finds from the Sacred Spring. Volume 2 of the Temple of Sulis Minerva at Bath. Oxford: OUCA, 1988.

Fagan, Garrett G. Bathing in Public in the Roman World. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Henig, Martin. Religion in Roman Britain. London: Batsford, 1984.

Ireland, Stanley. Roman Britain: A Sourcebook. 3rd ed. New York: Routledge, 2008.

Ogden, Daniel. Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds: A Sourcebook. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Tomlin, R.S.O. “Voices from the Sacred Spring.” Bath History. Vol. 4. Ed. Trevor Fawcett. Bath, United Kingdom: Millstream, 1992.

Versnel, H.S. “Prayers for justice, east and west: Recent finds and publications since 1990. ” Magical practice in the Latin West: Papers from the international from the international conference held at the University of Zaragoza, 30 Sept.-1 Oct. 2005. Ed. by R.L. Gordon and Marco Simon. Leiden: Brill, 2010.