For the Pre-Christian Sami people who inhabited parts of modern-day Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Russia, fishing was a livelihood. Like reindeer-hunting and herding, it was an arduous test of physical endurance and a regular opportunity to express reverence for spiritual forces. It was nothing like the contemporary cakewalk repetition of hook, line, and sinker. Indeed, for the Sami communities in Finland, it was much, much more.

These Sami held certain types of fish in high regard, believing that those which dwelled in the pure glacial lakes (such as Äkässaivo and Pakasaivo) were privy to otherworldly secrets. The scaly wise guys were thought to be the aquatic confidantes of the departed who set up house in the lake’s nether regions, the saivoaimo. How did the fish and the deceased communicate? According to tradition, the sáiva lakes had a double-bottom. Thus, the upper and lower worlds were linked by a kind of limen, an inter-dimensional trap door:

“The double-bottomed lake is associated with the idea of a stratified world; the lake offered access to the world below. The sáiva lake was inhabited by spirits in the shape of humans and animals that could function as protectors or help people to hunt or fish. Sáiva lakes were considered as sacred and offerings were brought to their shores.” (Äikäs, p. 44).

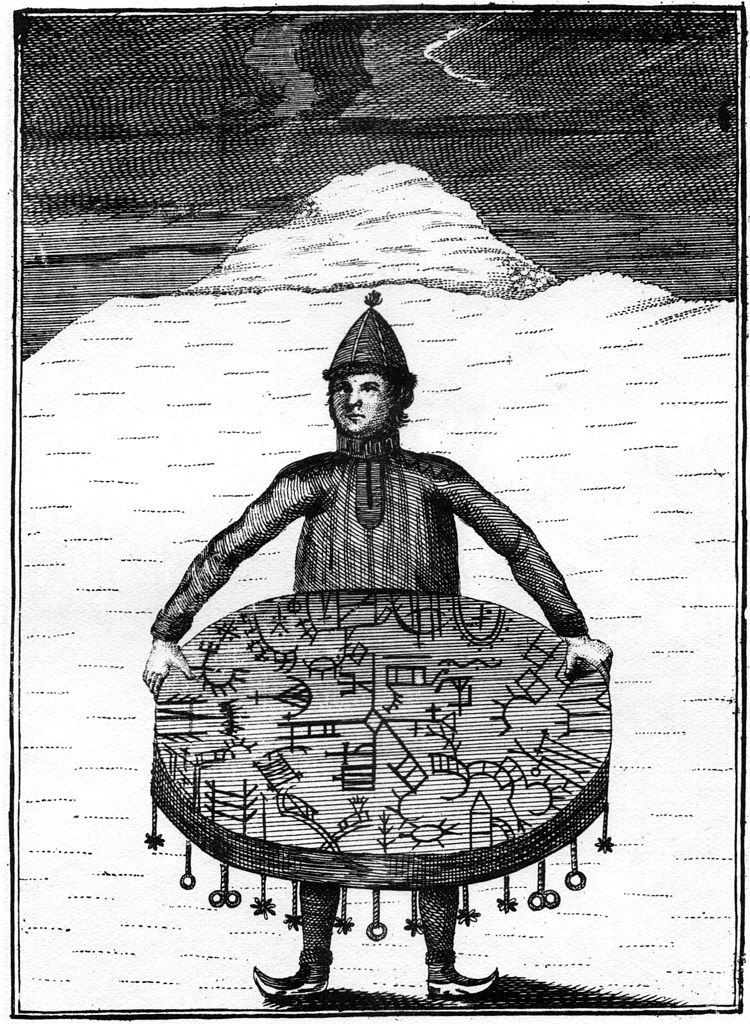

The only person who could access the sacred knowledge of the sáiva was an initiated interlocutor: the noai’de. The shamanistic role was limited to intuitive men who were prone to dreams and visions. With proper training, they could develop the power to ‘sleep’ with the fishes in trance and journey in spirit to the netherworld:

“By beating the drum faster and faster, the shaman started his soul journey to the spiritual world. As soon as he was entering into an ecstasy, he fell down on the ground, putting his drum on his back. In the dream, he encountered with his helping spirits for the consultation, although he could interpret how the indicator moved, and to where it pointed, due to his ability to reach any situation at will. He can leave the body and move to a spirit or a breath of wind in a trance, he can change himself into a reindeer; he flies over the tree tops; he swims in the shape of a fish…” (Niinioja, pp. 182-83).

Over time, the noai’de’s experiences building relationships with the sáiva spirits (also known as Noide-gadze) gave him tremendous insight into the nature of reality. It was this secret intelligence, provided by his ever increasing posse of disembodied beings, that enabled him to provide aid and counsel to his community:

“From that hour on the saivo-gadze began to have a more and more intimate intercourse with the young noidi, who could nominate as many of them as he liked for his guardian spirits. The greater the number of spirits which the noidi had in his service, the more powerful he was considered to be.” (Karsten, 67).

Hence, in the minds of the Sami fisherman, the sáiva lakes united two seemingly incompatible concepts: life and death. They fished in reverent silence, knowing that their source of food was also an integral part of their long-dead ancestors. It was the ultimate psychogeographical network, connecting the minds, bodies, and mores of generations. Even though the fishermen could only communicate with the spirits through the mediation of the noai’de, they knew that the lakes, which teemed with more than just fish, were more than alive.

References

Tiina Äikäs, 2015, From Boulders to Fells Sacred Places in the Sámi Ritual Landscape, Monographs of the Archaeological Society of Finland, http://www.academia.edu/17988252/From_Boulders_to_Fells_Sacred_Places_in_the_Sámi_Ritual_Landscape

Hee Sook Lee-Niinioja, 2014, Artistic Expressions of the Visual Language on Sami Ritual Drums, Akademia Kiadó, Polish Institute of World Art Studies. http://www.academia.edu/11320452/Artistic_Expressions_of_the_Visual_language_on_Sami_Ritual_Drums

Sigfrid Rafael Karsten, 1955, The Religion of the Samek, Brill.