Like most people, I first encountered fairy tales as a child. As in most children, the encounter generated mixed feelings—wonder and excitement, but also terror of the dark entities inhabiting Fairyland, the dragons and the witches and the ogres. In my late twenties, reading Borges and others, I became increasingly fascinated by the concept that all tellings of stories are re-tellings, and every story that every writer ever writes has been told, written or performed before. But as behind every adult there is a child, so behind every adult story there is a fairy tale—often many.

In the books I have written to date, whether in Greek or English, I’ve been constantly conscious of the basic fairytale patterns behind the plot and the characters I created, or rather re-created. In my earlier work, the seeds of the older stories survived only as faint echoes. But in my latest novel I have kept the fairy tale source very near the surface. Trying to understand the what, the how and the why I wrote a novel directly based on fairy tale, I cannot do better than return to some of the basic conflicts that define the genre.

- Kind vs. Form, or the Telescope and the Microscope

A zoologist can speak of an animal in two ways, either by studying the larger group to which it belongs, or describing its particular form. And so the shrimp in your plate can be spoken of either as a member of the phylum of arthropoda, or as having two eyes, ten legs, and an intestine running along the length of its body.

The classifying that Carl Linnaeus did for animals was originally done for folktales by two folklorists, Antti Aarne and Stith Thompson, and more recently amended by Hans-Jörg Uther. In its present form, the Aarne-Thompson-Uther (ATU) catalogue contains 2,399 types of folktales. Unlike Linnaeus neat taxonomic list, however, whereby each animal belongs to one and only one species, a story can be of more than one types. So, for example, “Hansel and Gretel” is ATU type 327A, known as “The Children and the Ogre,” but also type 1121, or “Man kills (injures) the Ogre.”

But a place in a list does not a story make. To understand the structure of a story we also need tools like those developed by the Russian folklorist Vlamidir Propp in his Morphology of the Folktale. Propp used methods of literary analysis to create a ‘formula’ describing some hundreds of ATU types, of the general class of “Tales of Magic.” For this he defined a cast of basic stock characters such as Hero, Villain, Donor, Victim, Helper, Princess, Dispatcher, False Hero, etc., as well as thirty-one narrative actions, which he called ‘functions,’ such as “An Interdiction is addressed to the Hero,” “The Villain gains information about the Victim,” or “The Hero is tested.”

A precise formula for describing things can also lead to an algorithm for creating them, which explains why Propp’s abstruse works are now standard reading in Hollywood. Script-analysts and script-doctors (yes, this is an actual speciality) use them to boost the narrative energy of screenplays.

- Oral vs. Written, or Granny and Madame d’ Aulnay

Most children growing up in Western cities, in the modern world, have their fairy tales read to them, out of books. Historically this is unnatural, though, as fairy tales were originally created and transmitted orally. In this they do not resemble short stories or novels, but proverbs, ballads or jokes.

Those of us who were fortunate to grow up near gifted storytellers know that the ear is a much better organ for a tale than the eye. Yet even who did not have this good fortune in their childhood, can now get a sense of the magic of live delivery from the new breed of professional storytellers, performing folktales in schools, community centers, pubs and theatres. An ancient tradition is coming alive again. To hear a tale told rather than read it, or even have it read to you, gives it an aura of the sacred, a sense that an ancient truth is being summoned from some immaterial repository.

But the revival of oral storytelling would not have been possible without the work of the collectors of the old tales. Great 14th-century writers like Boccaccio and Chaucer wrote tales influenced by the oral tradition. But it was only two centuries later, with Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone, that a book was created directly from oral material. A little later, the Baroness d’ Aulnay published her Contes de Fées, or “Tales of the Fairies,” which is also the provenance of the English word “fairytale.” In the collections of Basile and d’ Aulnay we find the first versions of great modern favorites, like “Sleeping Beauty,” (ATU type 410), “Cinderella” (ATU 510B) and “Goldilocks” (ATU 531.)

These early compilers felt no particular sense of responsibility to their oral sources. Still, what Basile, d’ Aulnay or the great Charles Perrault sacrificed in the way of fidelity, they made up for through narrative flair. Some of the tales that have been recorded by them may be distortions of their originals. But the form in which we have them today is indelibly marked by the talent of their recorders.

- Discovery vs. Invention, or the Brothers Grimm and Andersen

To most people, ‘a tale of the Brothers Grimm,’ and a ‘tale of Hans Christian Andersen’ means the same thing—with only the names differing. But there is a huge difference: a tale ‘of’ the Brothers Grimm is one recorded by them; a tale of Andersen, on the contrary, is one invented by him.

Though the Brothers Grimm are not the first collectors of tales, their talent and their energy have shaped a tradition. The two brothers were very different characters, Jacob Grimm a great philologist, linguist and legal scholar, and Wilhelm a poet and dreamer. But both were ardent Romantics, who believed that the spirit of a people, or Volk, was expressed in oral tradition. Though the view that the Brothers Grimm collected their tales through active field work and constant travel in Germany, or that they transcribed them exactly as they heard them from illiterate peasant tellers are exaggerations, their collection comes much closer to capturing a living oral tradition than anything before it.

The publication of collections by folklorists did not stop writers from taking their inspiration from the oral tradition. On the contrary, it provided the necessary impetus for the new genre of the invented fairytale. Hans Christian Andersen is the best known of its practitioners, creating his tales almost as if consciously playing around with the stock characters and actions—Propp’s ‘functions’—recorded by the folklorists. Traces of the oral tradition are visible in most of his tales, while some are directly modeled on tale types. For example, one of Andersen’s most famous stories, “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” is of ATU type 1620, also known as “The conversation of a one-eyed man and a hunchback,” a variation on the theme of a clever trickster.

Despite of the extent of his inspiration from oral folktales, however, most of Andersen’s stories would not have survived orally. They are so strongly marked by their author’s inner, dark, emotional conflicts that a living tradition would have filtered them out. Cultures don’t propagate tales that go against the survival habits of their members.

- Pink vs. Red, or Walt and Jack

The American folklorist Jack Zipes often refers to “Disneyfication,” or the domination of our culture’s idea of a fairytale by the standards imposed through Walt Disney’s filmic adaptations, like “Snow White,” “Sleeping Beauty,” and “Cinderella.” It is not so much that fairytale heroes have now acquired the looks and manners of American small-town beaus, and the heroines of their prom queens—which they have. A much more important effect is the ironing out of the complex symbolism, gray areas and moral ambivalence that characterize many tales, in order to conform to the black-and-white clichés of melodrama.

A good example of the power of “Disneyfication” is the tale of the “Three Little Pigs.” In fact, you can conduct a little test with your friends: ask them if they know the story, and if they reply in the affirmative have them recount it, briefly. In all probability—unless your friends are folklorists—most will do it wrongly. They will tell you the story this way: once the house of the first little pig, a house made of straw, is destroyed by the huffing and the puffing of the wolf, its owner runs to the second little pig’s house, which is made of wood; then, when that house is also destroyed, the first and second little pigs run to the third little pig’s house, made of bricks. But that is not the tale as it developed through oral retellings, over centuries and was made famous by being recorded in the Nursery Rhymes of England, collected by James Orchard Halliwell (1886.) In that version—incidentally, also the one that I first heard as a child—the wolf huffs and puffs, blows down the straw house of the first little pig and proceeds to eat the owner, as he does when he blows down the wooden house of the second; only the third pig survives, it actually eating the wolf, when he falls straight into his cauldron, coming down the chimney of the brick house.

The mush less sanguinary modern version is Disney’s, as narrated in his short animated film of 1933. In this, clean-cut family entertainment, the wolf is punished for his aggressive acts by a mere scalding of his tail. As for the three little pigs, they celebrate their victory over him by performing one more time the recurring ditty first introduced here: “Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?”

- Magic vs. Reality, or Folktales and Fairy Tales

The strongest effect of “Disneyfication” was the privileging of those tales whose plots can expand to cover a feature-length action film, suitable to be seen by a family audience. Shorter tales, especially if they did not contain the fantasy elements that make for spectacular cinema, became increasingly marginalized. This was a great shame, however, as some of the most interesting tale types are precisely of this variety.

After all, Madame d’ Aulnoy’s “tales of fairies,” or “fairytales,” are only a subclass of the much larger class of folktales. Short tales, realistic tales, as well as many religious or directly didactic tales, do not fit the description of “fairytale”—but are still, very much so, folktales.

A good example is the tale of ATU type 1430, that bears the generic name “Air castles.” The details of its various instances vary, but we find the same basic plot structure in the ancient Greek form “The Milkmaid and her Pail,” attributed to Aesop, in the ancient Indian of Vishnu Sharma, “The Broken Pot,” or in the version which is called “Lady Heinz,” in the Brothers Grimm collection. A version of ATU 1430 recorded in Russia captured the attention of no less a storyteller than Leo Tolstoy, who retells it in his “The Peasant and the Cucumbers.” The hero, a poor man preparing to steal cucumbers from a plantation, begins to dream of commercial success: he’ll use the stolen cucumbers’ seeds to grow more of them, then the seed of those to grow even more, and so on. One day he’ll be a hugely successful farmer, employing many guards to protect his produce from thieves—like himself. When one appears, in the future, his guards will shout loudly: “Thief!” Immersed in his daydream, the peasant actually shouts this, alerting the guards of the plantation from which he is about to steal the cucumbers, who give him a sound beating.

- Telling vs. Re-telling, or the Saint and the Dragon

As a child, I loved Karaghiozis, the popular Greek shadow-theatre. The most famous play in its repertory was “Alexander the Great and the Accursed Serpent,” whose story derives from a popular book of late antiquity called the ‘Alexander Romance.’

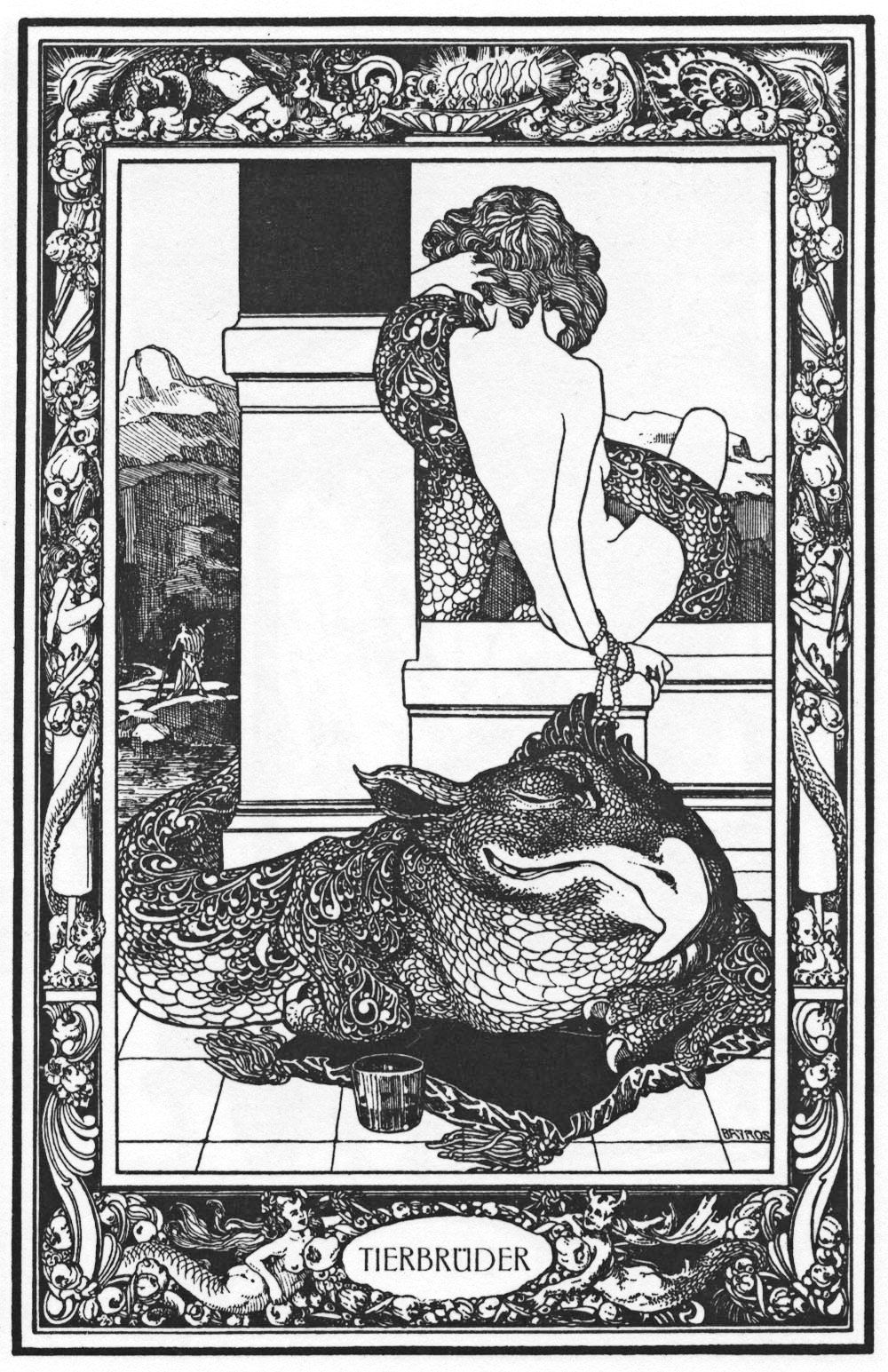

Though the hero of the ‘Alexander Romance’ is purportedly the great conqueror of the same name, its events are mostly garnered from the oral popular tradition, as is the central scene of the shadow-play based on it. This is known in scholarly circles as a theriomachy, from therion, meaning ‘beast’, and mache, for ‘battle.’ In the shadow-play, Alexander, here behaving like a typical hero of a folktale of ATU type 300 (“The Dragon-Slayer”) battles with the visually stunning Accursed Serpent of the title and, after much fuss, slays it.

Through their frequent re-tellings, folktales can so pervade a culture that they affect not only its ideas of history, as in the case of the ‘Alexander Romance,’ but its sacred narratives. The highly popular theme the Dragon-Slayer invaded even the story of the patron saint of England, Saint George. Although it does not appear in Western European versions of his life until the Crusades, the incident in which he saves a princess from a terrible dragon in the swamps of Libya was told in the East hundreds of years earlier. In fact, already in the 9th century it had become so prevalent that the austere Patriarch of Constantinople, Nicephorus I, felt the need to discredit it in writing, castigating the “monstrous exaggerations,” and the “rehashing of idle gossip”, that had intruded in the Greek version of the Vita Sancti Georgii. Yet, despite the patriarchal warnings, the story persisted. The saint is still painted today in the Eastern iconographic tradition as a dragon-slayer, and in Greece Saint George he is still popularly known as foniás, i.e. killer.

- Old vs. Very Old, or the Smith and the Devil

How old are folktales? The Homeric poems, which began to acquire the form in which we know them in the 8th century BCE, contain traces of many folk tale types. In Book 9 of the Odyssey, for example, when Odysseus tricks the Cyclops, Polyphemus, we have direct evidence of ATU type 1137, belonging to the more general class of “Man kills (injures) Ogre.” If we look eastwards, we find indications of the same tale type in the Epic of Gilgamesh, four centuries earlier, in the scene in which the eponymous hero and his friend Enkidu defeat the monstrous Huwawa. But there is no reason to think that folk tales don’t go further back in time—in fact, there are many reasons to think that they do.

In order to trace more ancient roots, literary theorist Sara Graça da Silva and anthropologist Jamshid J. Tehrani have recently applied to the data of the Aarne-Thompson-Uther catalogue techniques originally developed in evolutionary biology, as well as sophisticated statistical methods. As a result of their research, a tale type which was recorded as late as a few decades ago as part of the living oral tradition of the Travelling people of Scotland, was found to have begun its life some millennia earlier than Gilgamesh and Odysseus. This is ATU type 330, known as “The Smith outwits the Devil,” belonging to the larger class of “Supernatural Adversaries.” In the form of it that we find in the Grimm Brothers collection, by the title of “Brother Lustig,” the tale bears the mark of the Christian tradition, as the beneficent magical object is given to the hero by Saint Peter. Despite this, as well as the fact that the hero is not a smith but a discharged soldier, the core of the plot is that of the ancient tale: a clever man tricks a demon and manages to put him in a magical bag. The research of da Silva and Tehrani gives strong indication that folk tales could be as old as the beginning of human culture, in fact as old and language, myth and ritual.

- Delight vs. Teaching, or the Performer and the Sage

That folktales can be entertaining is obvious to anyone who loved them as a child. In fact, they can be entertaining even when they contain ogres and witches, and this for the same reason that crime stories or horror films can be entertaining—darkly so, but still entertaining. But entertainment is not their sole purpose.

One needs to become a parent, or at least to have the experience of frequently telling tales to young children, in order to start thinking about their other uses. My own ideas about the matter were partly shaped by the book of the Austrian-born psychologist Bruno Bettelheim, The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. Based on his study of folktales, Bettelheim makes a strong argument against much of modern children’s literature, which tends to shun the horror often present in them. In this sense, he is all for the pre-Disney version of the “Three Little Pigs,” in which only the third pig survives.

Actually, Bettelheim thinks that fairy tales are essential to the emotional well-being of a child precisely because of the horror. But he is also a supporter of the Grimm Brothers versions of it, and not of Andersen, in other words of the horror that can successfully pass the test of a living popular tradition. In two words, the main criterion of this success is: happy ending. Like the heroes of one of the most horrifying fairy tales, “Hansel and Gretel,” Bettelheim had met horror face to face—and physically survived it—as an inmate of the death-camp of Buchenwald. This experience was his major formative experience as a psychologist, and also the one that made him see profound meaning in fairy tales. Yes, life is full of hardship, horror even, and this truth cannot be hidden from children. But at the same time they must be given the emotional guidance to be able to face the horror successfully. In Bettelheim’s view, fairy tales are psychological parables that can guide young readers through the emotional labyrinths of growing up, giving them a foretaste of a complex, difficult and often evil world, but also pointing at ways of getting out of it in one piece.

Finale: Pleasure Principle vs. Reality Principle, or Life and Death

An ardent Freudian, Bruno Bettelheim sees the old English tale of the “Three Little Pigs” as embodying the conflict of the Pleasure Principle with the Reality Principle. When my three children were little, I told the tale to them with Bettelheim’s idea in mind, trying to communicate through a lively performance that they must learn to be in life like the third little pig, not its mindless siblings. But the more I thought of the tale, the more I sensed that there was something deeper in it. There was of course the obvious message, of the value of delaying gratification. Yet there was something more: an allegory of facing the most terrible of threats to a living entity, the threat of extinction.

In “Three Little Pigs”, each piggy creates a barrier to keep out death, the first one of straw, the second of wood, the third of bricks. But what happens, I began to wonder, if one wants to go beyond allegory? Like children, adults too fear death, although most of the time we tend to forget the fear or rationalize it away. Yet sometimes death acquires a face in our lives, as concrete and threatening as that of the Big Bad Wolf. Who is afraid of him, then? Well, we all are. So, what do we do? What barriers do people, not piggies, resort to, to protect ourselves against the very real threat of death? What are “straw,” “wood” and “bricks” for an adult?

Trying to answer those questions, for myself, I wrote a novel. Unsurprisingly, it is called Three Little Pigs.