While gnomes are a popular staple of fairy tales and fantasy, they trace their origins back through alchemical theory to Greek and Roman mythology. Diminutive cave dwellers variously associated with earth, precious metals and good fortune, reports of gnome sightings have persisted into the present day.

Most people will be most familiar with gnomes as jovial garden ornaments, colourful representations of a subject popular with many 18th century writers, particularly of the Romantic movement. While it would be easy to assume that gnomes trace their origins back to European folklore, much like similar creatures such as the Germanic kobold or British hobgoblin, their origin in reality lies with the alchemical theory of the Renaissance.

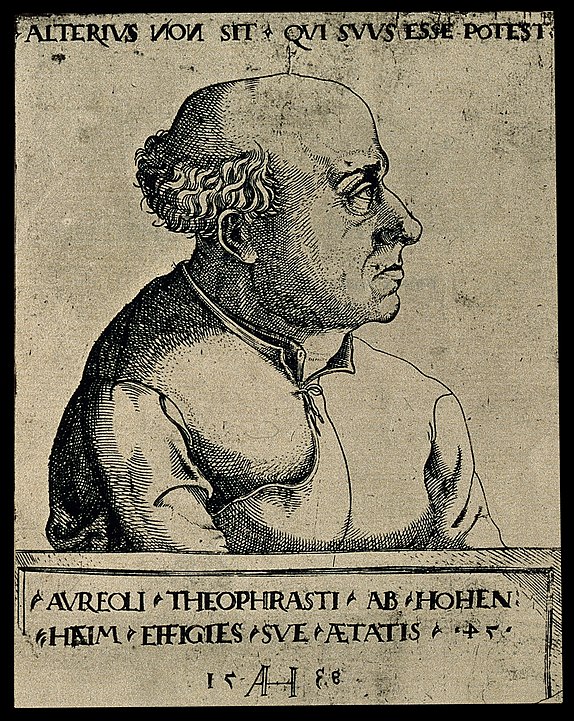

The diminutive beings known as gnomes were first described by the Swiss physician and keen student of alchemy Paracelsus during the 16th century, one of four beings that each represented one of the four Empedoclean elements of earth, fire, water and air. The short, chthonic gnomes represented earth, alongside the undine (water), sylph (air) and salamanders (fire). The name itself likely derives from the Latin genomos, meaning earth-dweller.

While modern parlance would describe these as elementals, Paracelsus himself did not use the term, instead believing them to be something part way between an animal and a spirit. While considered invisible to humans they were otherwise physical beings, requiring food, sleep and clothing much like we do. Each were able to move freely through their own element, allowing gnomes to pass through rocks, walls and soil as effortlessly as a fish through water. Each would remain healthy when surrounded by their own element but would sicken and die if exposed to others. Collectively, the four beings were known as the sagani.

While the undine were described as the most humanlike in appearance, the coarser, stronger sylphs were said to be most like us by Paracelsus, moving through air as we do but drowning in water, burning in fire or being trapped in rock. Paracelsus theorised that these various beings differed from humans as they lacked an immortal soul. However, by wedding a human the elemental, and their subsequent offspring, could obtain a soul of their own.

Each of the elementals described by Paracelsus appear to be inspired by older mythologies, particularly drawing on Greek and Roman tradition. The undine closely resemble the water spirits known as nymphs. Sylphs also draw connections to wood nymphs and fairies as well as taking inspiration from the wild man of medieval European folklore, itself influenced by the satyrs of classic mythology. The salamanders of folklore were described in the writings of Pliny the Elder and appear frequently in European stories, their connections to fire often seeing them grouped alongside dragons.

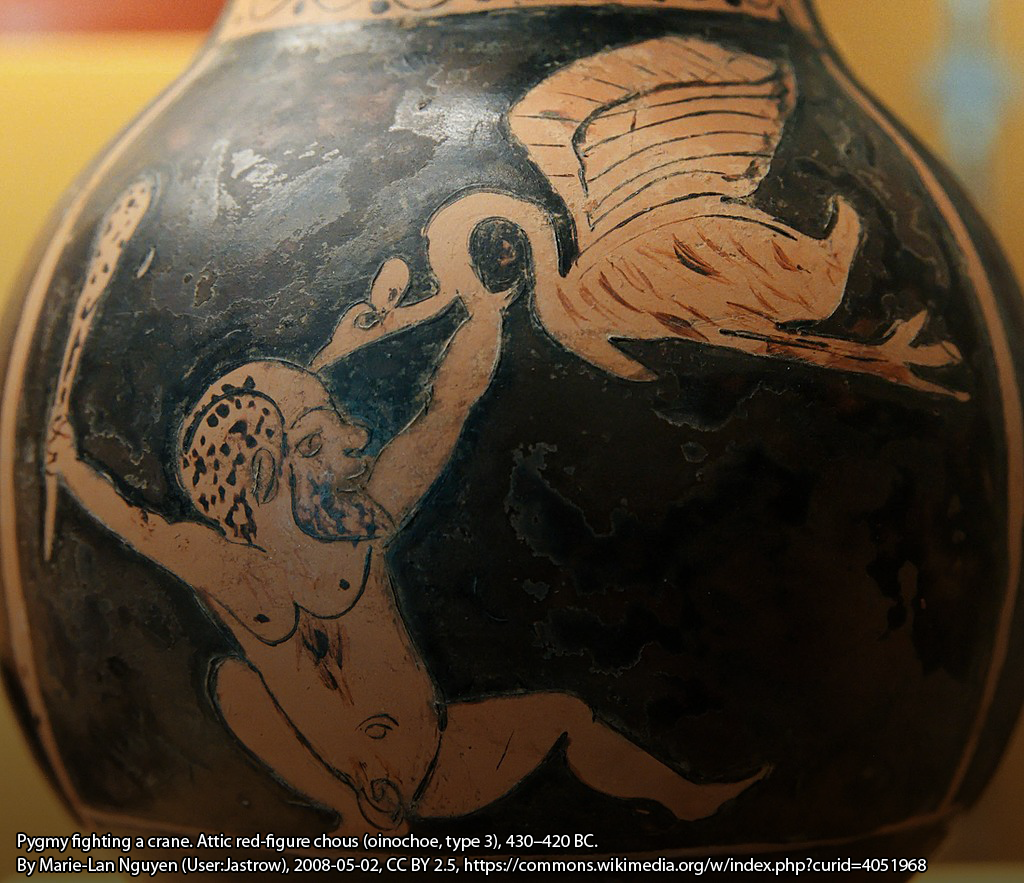

In the case of gnomes, Paracelsus appears to have been influenced primarily by the description of mythological creatures called pygmies, reminiscent of fairies or gnomes. Featured in The Iliad, the pygmies were described as diminutive humanoids less than three spans in height (the distance between the tip of the thumb and little finger on an open hand). They lived in a remote, mountainous region where they conducted an ongoing war with the cranes, who would migrate to the pygmies’ homelands every winter. A popular subject of red-figure pottery, pygmies were almost invariably depicted battling flocks of cranes or herons. Later Greek writers placed them as living in various places around the world, with no relation to the outdated 19th century terminology used by Victorian explorers to describe some peoples of the Congo basin.

This animosity between the two factions was said to have begun after the queen of the pygmies, Gerana, made the foolish boast that she was more beautiful than the goddess Hera. Vindictive and easily provoked, the wife of Zeus transformed Gerana into a crane for her insolence. The pygmies were said to lead regular raids into the clifftop homes of the birds, armed with bows and mounted on rams or goats, devouring eggs and chicks to prevent them growing into adult birds that would further plague them.

A number of prominent Greek and Roman writers described tales of the pygmies and their eternal war. Pliny’s Natural History gives us their size and the description of their mounted raids on the homes of the cranes, as well as stating their houses were crude constructions of mud and plundered feathers and eggshells. Pliny himself acknowledged that here he differed from the earlier writings of Aristotle, who described them as living underground, but otherwise their accounts tallied closely.

Following their conception in Renaissance alchemical theory, gnomes became a popular subject of 18th century fairy tales and romanticism, their traits often changing to suit the needs of the writer but their short stature and close association with the earth and underground generally remaining consistent. The term gnome was introduced to many readers by the mock-heroic narrative The Rape of the Lock by poet Alexander Pope. The poem satirises an incident of the theft of a lock of hair from the young woman Arabella by her suitor. The title derives from the Latin rapere, meaning to snatch or carry off, an incident that in the narrative results in an ongoing feud between the two families.

The poem mocks the relatively benign incident by comparing it the feuding of the Greek gods, represented in the story by Paracelsus’ four elementals. The differing natures and world views of gnomes and sylphs results in them battling futilely throughout the mock-epic to influence the behaviour of the heroine. The popularity of this poem did much to establish the term ‘gnome’ in English parlance.

By the 19th century they had lost much of their individual character, largely becoming synonymous with similar creatures, particularly goblins. They were frequently described as an antithesis to fairies, ugly, slow and associated with darkness and underground places as opposed to fairies and their associations with nature, light and beauty.

Today, gnomes are widely considered a creation of fairy tales rather than possible living creatures successfully hiding their existence from humanity. However, that is not to say that they are without reported sightings. In 1979, a group of children reported witnessing a bizarre procession in the grounds of Wollaton Park, close to the centre of Nottingham, UK. They described a column of up to thirty tiny blue cars, each carrying a gnomish driver and a passenger wearing tights, blue tops and bobble hats. The story received significant media coverage at the time but no further sightings of the strange vehicles or their occupants were ever reported. Nevertheless, belief in their existence continues; in a ‘fairy census’ carried out by the Faery Investigation Society in 2014, a portion of the 450 responses described sightings of gnomes.

Modern readers likely most closely associate gnomes with the image of a bearded, smiling figure wearing a red pointed hat, commonly represented in garden ornaments across the world. This portrayal of gnomes draws heavily on the design of the dwarves from the 1937 Disney animation Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, released at around the time that garden gnomes began to gain popularity. However, older statues of wood or porcelain date back to at least the late 1700s. Their associations with healthy gardens and good luck remain one of the few links back to their alchemical origins, beings representing the unmoving earth and stone we walk upon and which provides nourishment to the plants we tend and eat.

References and Further Reading

- Jason Josephson-Storm, 2017, The Myth of Disenchantment, University of Chicago Press

- Alexander Pope, 2007, The Rape of the Lock, Vintage Classics

- S Lewis, 2012, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature, Canto Classics

- Paracelsus, 1996, Four Treaties of Theophrastus Von Hohenheim, JHU Press

- Pliny the Elder, 1991, Natural History, Penguin Classics

- Philip Ball, 2007, The Devil’s Doctor, Arrow