Austronesian traditions mingle with German tales, while continental Asian lore is blended with that of the Pacific—such fusions form the roots of Taiwanese folklore. The island of Taiwan is located off the far eastern coast of the Eurasian continent, between China, Japan and the Philippines. Straddling key geographic crossroads, the island’s tales and traditions clearly reflect its location at the edges of worlds, cultures and empires, having been a colony of European, Chinese and Japanese regimes at various points in its history. The resulting intercultural interaction, borrowing, and mixing, has shaped folk life in Taiwan over the centuries.

Taiwanese folklore may be conveniently, albeit inaccurately, divided into two very general categories—those of the indigenous Austronesians living in the highlands and those of the Han or Chinese-speaking (Taiwanese, Hakka and Mandarin) peoples living in the lowlands. But a closer look at Taiwanese lore reveals the true international, eclectic and intercultural roots of Taiwanese folk culture. The dichotomy is a convenient way to sort through the tangled web of tales and traditions found on the island today, but their origins are far more complex.

The Mute Maiden

One folktale that demonstrates the complex history and origins of Taiwanese folklore is The Tale of the Mute Maiden (Yǎnǚ de Gùshì). The story is passed down orally among the indigenous Puyuma people of Taiwan’s southeastern highlands and is an integral part of their unique heritage.

In brief, the story tells of an orphaned maiden who grew up in the care of a loving adoptive mother. One day, however, the young maiden opened a door to a secret chamber in her adoptive mother’s house—an act which was explicitly forbidden. When the adoptive mother demanded that the child confess to her trespassing, the girl lied, and for this she was banished.

While in exile, the young maiden was rescued by a chieftain. The two soon fell in love and were married. But on the day the young couple’s first child was born, the maiden’s adoptive mother appeared and once again demanded that the maiden owned up to her transgression. Once again, the maiden refused and her child was taken away from her. This happened again and again over the next few years until, at last, the maiden confessed and her children were restored to her.

This strange tale was presented as one stressing the importance of honesty and forgiveness.

Readers familiar with Grimm’s fairy tales, the 19th-century collection of German folk stories, will surely notice similarities with the German tale Our Lady’s Child. The two stories are virtually identical, with indigenous Taiwanese elements replacing German equivalents: The mysterious adoptive mother replaces the Virgin Mary in the German version and her “home,” in the European tale, is the Kingdom of Heaven. How can this be? How can an age-old German fairy tale have an equivalent among the deeply isolated Puyuma people of Taiwan on the other side of the planet?

It is known that European missionaries were active in Taiwan long before the first Chinese settlers began colonizing the island. As early as the 1600s, Christianity was being proselytized among the indigenous Austronesians of highland Taiwan. It is likely that during these early cross-cultural interactions, European fairy tales found an audience among Taiwan’s Puyuma people and were subsequently transformed into Austronesian folk tales. Today, that is how this story is still being passed down in Taiwan, as an indigenous folk story, but with clear European origins.

The Rat’s Bride

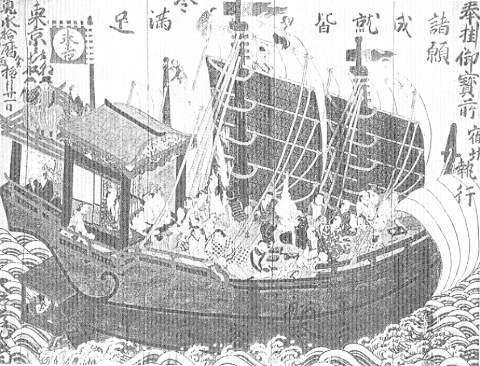

Another Taiwanese story, this one popular among the island’s lowland Chinese-speaking communities, is The Rat’s Bride (Lǎoshǔ Qǔxīnniáng). This tale is closely linked to Lunar New Year (Spring Festival) celebrations in Taiwan.

A Taiwanese custom demands that, on the third eve of the Lunar New Year, rowdy children are to be sent off to bed early; for, on this night, the rats hold their weddings and, of course, it would be rude to disturb them.

According to the tale, once upon a time, an old rat went off in search of a suitable candidate to whom he could betroth his only daughter. The key criteria: the bridegroom must be more powerful than the cat—the rats’ natural enemy.

During his search, the old rat encountered the Sun, the Cloud, the Wind and the Wall. Each one boasted of being the most powerful thing in the universe, but each, in turn, was trumped by another. The Sun’s life-giving rays and warmth were blocked out by the Cloud, which in turn was blown away by the Wind, whose gales were stopped by the Wall. Finally, whilst the Wall boasted of its impenetrability, a small rat burrowed right through it. This proved to the old rat that, at the end of the day, the most suitable candidate to marry his daughter was a fellow, humble rat.

As mentioned above, the folktale is popular among Taiwan’s Chinese-speaking communities. Similar tales exist throughout the Far East and, in 1904, a Japanese version was notably published by the Scotsman Andrew Lang in his “coloured” Fairy Books.

Interestingly, two other stories bear striking similarities to the tale of The Rat’s Bride. They are The Stonecutter from Japanese folklore and The Fisherman and His Wife published by the Brothers Grimm.

Folk tales and traditions often cross cultural, political and linguistic boundaries. Taiwan’s location, on crossroads and frontiers, further facilitates this intercultural process. The result is a fascinating blending of cultures as diverse as those of Germany, East Asia and indigenous Pacific peoples. This blending of cultures is reflected in Taiwan’s folklore.

The two stories presented above merely scratch the surface of Taiwan’s wonderfully eclectic folkloric roots. Over the ages, colonists, traders and empire-builders from Europe, China and Japan brought their traditions with them to Taiwanese shores and their stories have continued to mixed with those of the indigenous Austronesians to produce today’s fascinating universe of Taiwanese folklore.

References & Further Reading

Gary Marvin Davison, 30 Aug 2004, Tales from the Taiwanese, ABC-CLIO

Monica Chang, 4 Mar 1994, The Mouse Bride, Yuan-Liou Publishing

Ronghua Jin, 1 Jun 1997, On Folk Stories (in Mandarin; Minjian Gushi Lunji), Sanmin Books