When I was six, the Fair Folk were my allies and I had the paperwork to prove it.

We finalised our contract at the bottom of the garden. I used a fork to stake a note to the ground before bedtime. I told them I had complete faith in fairies and was the perfect candidate to be their human friend. When I came outside the following morning, padding down past the shed in my nightie, I was ecstatic. In skittish red handwriting, on WHSmith notepaper, they said they would love to be my friend.

I didn’t mind that we never had any tea parties or Cottingley photoshoots. My belief in fairies was quite pragmatic. After all, I now knew that they used biros. But part of me still wanted the Labyrinth fantasy – to be swept up and away from the mundane.

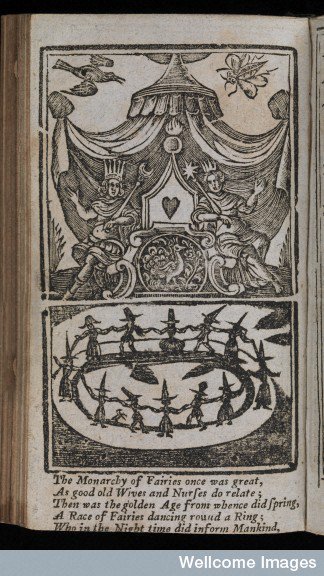

When we think of fairies now, many of us turn to Disney’s animated Peter Pan. But J.M. Barrie’s Pan plays were never originally meant for a child audience. Part of the problem was that Pan was too traditionally fae. He didn’t benignly find children to run away with, Barrie explained – he stole them. Pan was heartless, and Tinkerbell was vindictive. The play was later stripped of references to death and Yeatsian occultism, and sweetened with lines like ‘when a new baby laughs for the first time a new fairy is born.’ Barrie probably knew this didn’t apply to the Red Cap fairies of the Scottish border who dyed their hats with human blood.

As Peter Pan passed into modern lore, the traditional malevolence of fairies was almost drowned out by Disney cuteness. To be led astray, Peter Pan style, by a fairy – ‘pixie led’ – is an old fear from isolated communities where weather and terrain seemed to judge and punish. In 1890, folklorist William Crossing wrote in his Tales Of The Dartmoor Pixies:

Numerous are the instances of folks having been pixy-led and obliged to wander about on the moor […] many are the incidents related of people having been plagued or frightened in various ways, who have gained the displeasure of the goblins.

One such tale from Dartmoor tells of a farmhand who heard strange calls going out across the moors. When it became clear the voices were calling his name, the lad ventured out and vanished. His friends were confident ‘the piskies’ would only keep him for a year and a day, but he was never seen again and no body was ever found.

In Strange and Secret Peoples, Carole Silver explains that such experiences were rich with symbolism, making them ripe for fiction:

To be pixie-led was to experience the “uncanny”; it was to be taken across the border between the civilized and the wilderness, to have the familiar become strange and the known become “other.”

Fairies represent what we want, particularly when those things are attached to anxiety or guilt. In the upside-down world of the fairy, we are given permission to act out our secret desires. We see it in Labyrinth when Sarah gives up her baby brother to the Goblin King, and in Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell when Gilbert Norrell abandons his principals in favour of the prestige that comes with fairy magic. Fairies represent the part of the psyche that want-want-wants and lands us in deep trouble.

This push-pull quality is, I think, what keeps fairies alive in our cultural consciousness. We have long used fairy language to classify otherwordly features in people we are attracted to, and people we distrust. We still talk about arty people being ‘fae,’ the mad as ‘touched,’ and troublemakers as ‘trolls’. When Jane Eyre startles Mr Rochester’s horse, he accuses her of being a faerie:

No wonder you have rather the look of another world. I marvelled where you had got that sort of face. When you came upon me in Hay Lane last night, I thought unaccountably of fairy tales, and had half a mind to demand whether you had bewitched my horse.

It’s flirtation and intimidation, but Rochester’s words also herald Jane as a being who will change his destiny, perhaps for better, perhaps for worse.

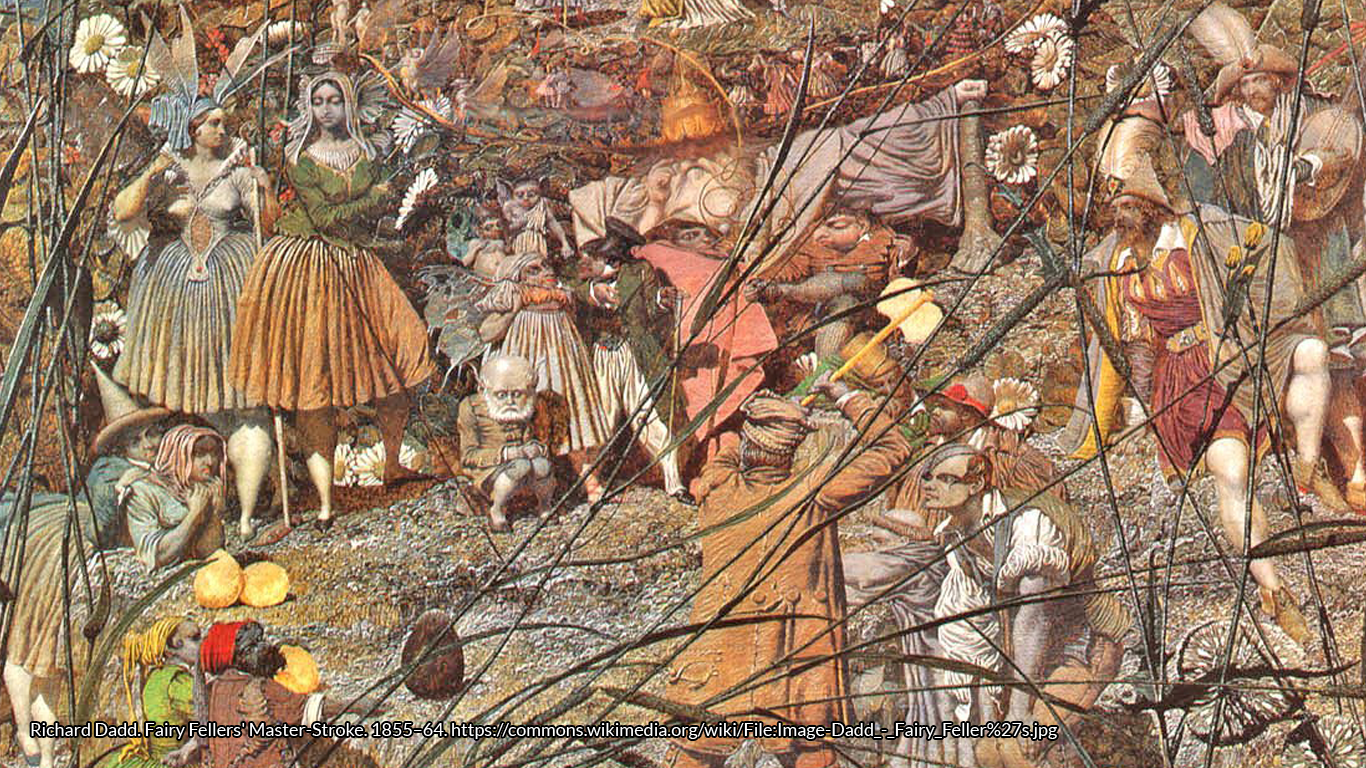

To be ‘touched’ or ‘kissed’ by the fairies is a folk idiom similar to bewitchment, with the added threat of derangement. The Victorian painter Richard Dadd is known for his intricate paintings of fairy scenes, and also for his contrastingly violent history. Dadd killed his own father in 1843, believing him to be the Devil. Pronounced criminally insane and taken to Bedlam, he continued to paint fairies peacefully for the next twenty years. But these artworks, delicate and beautiful though they are, always carry an undertone of threat. Strange beaked figures leer over sleeping humans, while tiny, musclebound men hold hammers poised to strike. Dadd is something of a cult figure today, his tragic life inspiring songs and novels. It is as if we’re still beguiled by the possibility that the fairies made him do it, or gave him permission to act out his heart’s most anarchic desires.

To be pixie-led is to be freed from the constraints of one’s daylight self. It’s no accident that we’ve ended up with the trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, the carefree young woman who serves no purpose but to inject whimsy into the male protagonist’s life. She is a de-clawed fairy, but the essential purpose remains – to whisk the human out of the mundane and into the ‘other.’ However, to bargain with a true fairy is to roll to dice with fate: Sarah must face ‘dangers untold’ in the Labyrinth, Mr Norrell will unwittingly damn a young woman to fairy captivity, and even Mr Rochester, with his very human Jane Eyre, will lose his home and his sight. But in all these stories, the protagonists discover the hidden side of their own nature, noble or otherwise. The ‘otherness’ is inside them, and the fairy is merely the catalyst.

What’s at the root of the pixie-led phenomenon, I think, is the belief that power, good or bad, always lies in people and things other than ourselves. Looking back at those Dartmoor tales of misfortune out in the elements, it’s easy to understand why. Some versions of the pixie myth tell us that the only remedy for their mischief is to laugh out loud in defiance. If, as Carole Silver writes, to be led astray by a pixie is to have the familiar become strange, perhaps the antidote to that spell is to allow the strange to become familiar, to open up to the ‘other’ and see what it has to teach us about ourselves. And perhaps we ought to do it before the pixies have a chance to wreak their havoc.

Do check out Verity’s new novel from Unsung Stories, Pseudotooth:

The debut novel from Verity Holloway, Pseudotooth is an adult take on ‘portal fantasy’, boldly tackling issues of trauma responses, social difference and our conflicting desires for purity and acceptance. Aisling Selkirk is a young woman beset by unexplained blackouts, pseudo-seizures that have baffled both the doctors and her family. Sent to recuperate in the Suffolk countryside with ageing relatives, she seeks solace in the work of William Blake and writing her journal, filling its pages with her visions of Feodor, a fiery East Londoner haunted by his family’s history back in Russia. But her blackouts persist as she discovers a Tudor priest hole and papers from its disturbed former inhabitant Soon after, she meets the enigmatic Chase, and is drawn to an unfamiliar town where the rule of Our Friend is absolute and those deemed unfit and undesirable disappear into The Quiet…Blurring the lines between dream, fiction and reality, Pseudotooth boldly tackles issues of trauma, social difference and our conflicting desires for purity and acceptance, asking questions about those who society shuns, and why.