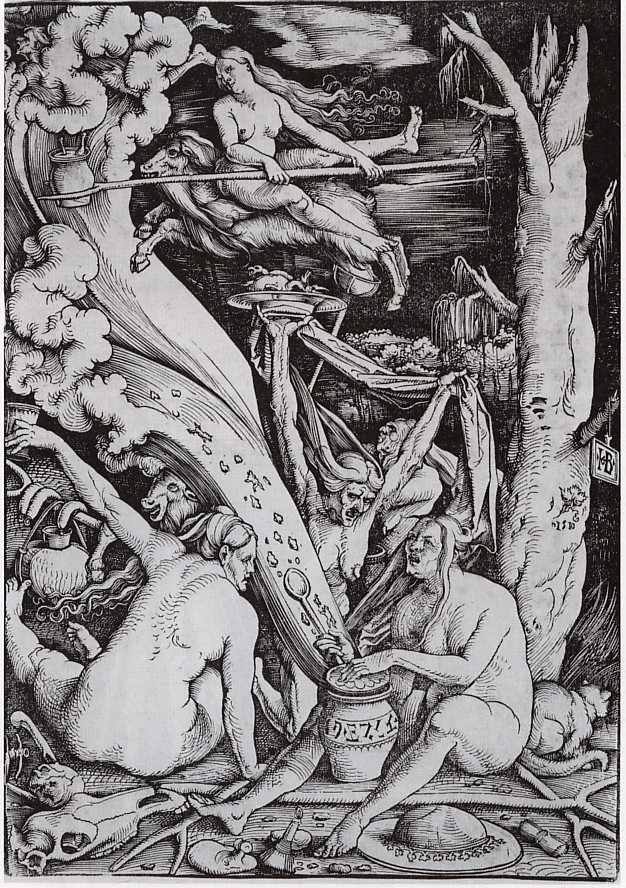

The concept of a witch, that is a practitioner of magic, has been part of western folklore for centuries, yet throughout that time it has been subject to continuous reinterpretations. She – for the witch is almost always a she – is old, ugly and nearly blind, who lives in a house of gingerbread and fattens up children for dinner. At the same time, she is a beautiful queen, overcome with vanity and jealousy, willing and able to use magic for murder. Finally, she is the teenage girl, attending a school of magic, but still suffering all the ups and downs of adolescence.

The exact characteristics that make up a witch are fluid, changing to reflect context, established folklore and imagery, and religious convictions. However, these constructions are bound to a single archetypal image, allowing for such different ideas to all be characterised under the one name – ‘witch.’

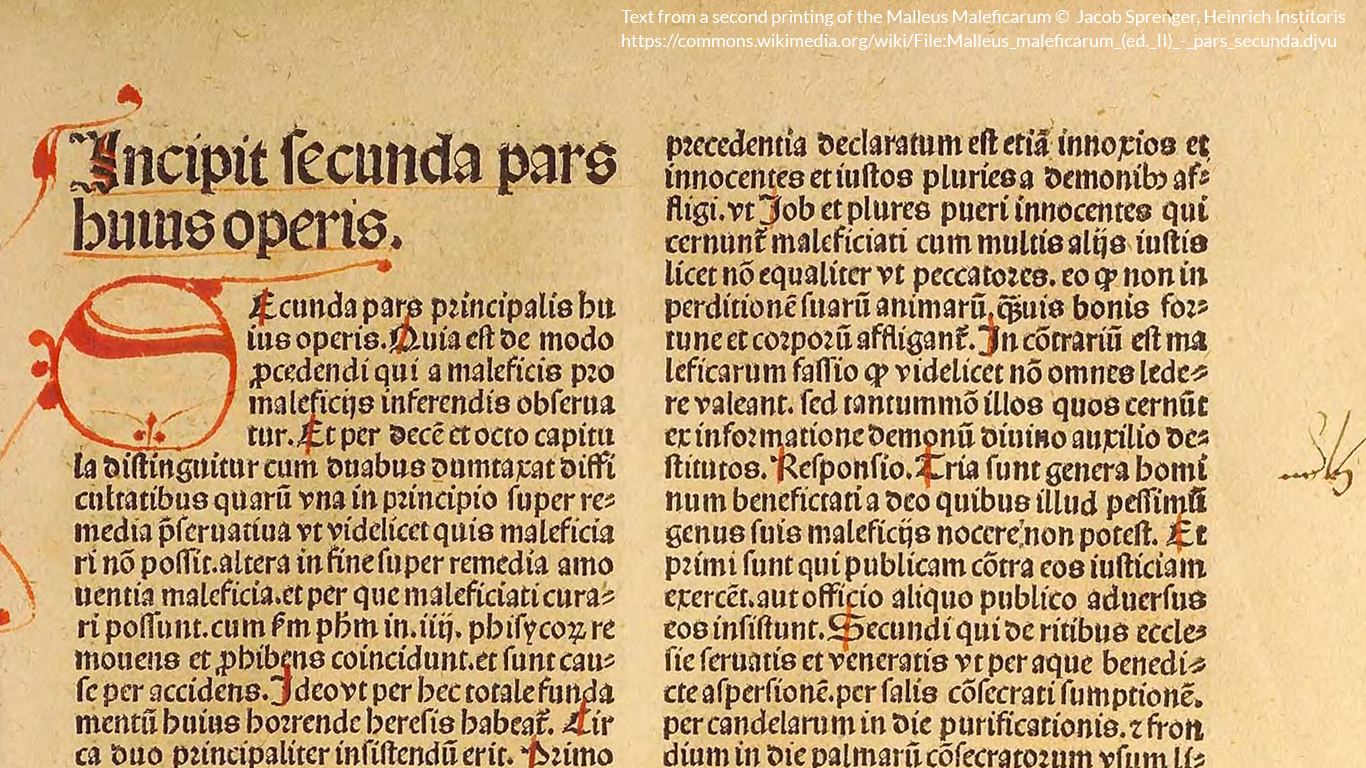

First published in 1486, the Malleus Maleficarum, or Hammer of Witches, is believed to have been one of the main texts used to define the witch and to promote the persecution of the same during the early modern European period. The text was written by the Dominican Inquisitor, Heinrich Kramer, and outlines methods to recognise witches, and advises on the appropriate punishments for witchcraft.

Set up as a discussion, the Malleus presents a series of questions and answers over three distinct sections. Each of these sections builds on the one before it:

‘Section One’ addresses the reality and/or efficacy of witchcraft;

‘Section Two’ describes the methods a witch uses to achieve her aims;

‘Section Three’ details the appropriate punishments for those convicted of witchcraft.

The witch presented in the Malleus heavily influenced the dominant image of the same for a considerable period of time and, in some ways, still does today. The idea of witchcraft in the text is a constructed image, heavily based on theological, folkloric, and pre-existing ‘academic’ ideas of magic and its practitioners, and thus brought nothing new to the early European ideas of witchcraft. Instead the Malleus, to quote R. J. Thurston; “presented the witch stereotype in a complete and well-organised fashion,” making it a key text for witch hunters during the persecutions of the early modern era.

The connection between witchcraft, demonology, and heresy is arguably the key tenet of the Malleus Maleficarum and has its origins in ancient Christian ideas of magic. As Hans Peter Brodel notes; magic, from the earliest of Christian history, was closely related to idolatry. Ancient practitioners would invoke the powers of various gods or spirits to perform magic. Thus, for example, in the Old Testament, Pharaoh’s magicians were able to imitate the miracles performed by Moses.

As Christianity became the dominant religion in Europe, and with pagan religions dead or dying, the gods and spirits of the old religions were interpreted as either demonic spirits or powerful practitioners of magic who worshipped said spirits. Once this connection had been made, Christian theologians began to argue that any sort of agreement with a demon implied the denial of god and thereby amounted to heresy. Thus, from the thirteenth century onwards, practitioners of magic were increasingly identified as heretics, while aspects of magic that had previously been thought of as natural were slowly identified as demonic.

Indeed, Kramer was careful to address the connections between witchcraft, demonology, and heresy early on in his work. Part One, Question Two of the Malleus is devoted entirely to the topic of whether a witch or a demon can effect magic by themselves, or whether they must work together. Kramer asserts: “it is always necessary for the demons to co-operate with sorcerers,” and consistently refers to this argument throughout the text.

Although Kramer’s ideas on the relationship between magic practitioners and demons are key to his work, they are not among the most lasting. Rather, the Malleus Maleficarum is regarded as the key text in promoting the idea of witches as exclusively female, which is a stereotype that still exists today. That Kramer himself believed the primary practitioners of witchcraft to be women is obvious, both in the structure of his text and in its name.

Regarding the former; of the 79 questions/subsections of the Malleus, only three directly refer to male practitioners, with all other sections being either gender neutral or directed at women. At the same time, excepting those three chapters, every anecdotal example of witchcraft provided by Kramer specifies a woman who has in some way cast an enchantment.

Kramer used the feminine genitive plural of the Latin ‘maleficus’ – ‘maleficarum’ – in the title. Thus, Malleus Maleficarum translates as “Hammer of (Female) Witches.” As a result of this gender bias, most scholars assume that the Malleus is a work of misogyny, aimed specifically at the persecution of women. And Kramer himself seems to have distrusted women immensely, and was known to be free with his accusations.

However, others have suggested that to label the Malleus as misogynistic is problematic because it aligns with modern morality and sensibilities. Stuart Clark has suggested that the gender bias present in the Malleus may have more to do with the binary nature of classification that was developed in, and survived from, the ancient world (e.g., fire and water; sacred and profane; men and women). He argues that while this is technically misogynistic, it is not necessarily malicious.

The image of witches and witchcraft created by Kramer in the Malleus Maleficarum is one of the most enduring and influential representations of the witch. Although the Malleus was thought to have held a huge amount of sway over the persecution of witches during the European Witch Hunts, its influence seems to have been much more widely spread. Elements of Kramer’s witches appear in the stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, the witches of various Disney films, and even in J. K. Rowling’s Wizarding World.

References

Briggs, Robin. Witches and Neighbours: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 2002.

Brodel, Hans Peter. The Malleus Maleficarum and the Construction of Witchcraft. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003.

Clark, Stuart. “Witchcraft and Magic in Early Modern Culture.” In Withcraft and Magic in Europe: The Period of the Witch Trials, 97-170. London: The Athlone Press, 2002.

Kieckhefer, Richard. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Mackay, Christopher S. The Hammer of Witches: A Complete Translation of the Malleus Maleficarum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Thurston, Robert W. Witch, Wicce, Mother Goose: The Rise and Fall of the Witch Hunts in Europe and North America. Harlow: Longman, 2001.