Spinning is one of most ancient things that makes us human. Many would say one of the first is making basic tools – shaping a stone to hit things with, while many would put making string as the second. You can’t do anything without string: you can’t make clothes; you can’t tie a stone to a stick to make a hammer; you can’t make nets to carry or catch things. Spinning is a fundamentally human thing, and something that we have been doing since far back into the ancient past.

The first length of thread would have been no longer than the distance between two extended hands, then it was wound round a stick and made longer. The first wheel was probably made after watching a spindle whorl rolling along the floor.

Spinning is the oldest textile skill. Then comes knotting and netting – vital skills for our hunter-gather ancestors to make bags to carry food and nets to catch food. Weaving cloth in any amount came along in the Neolithic Period, when people were settled enough to set up their simple looms (made from sticks and pegs).

People used plant materials to make string long before someone tried animal hair. Materials such as climbing plant stems, the inner bark of certain trees, and dried grasses. Twist gives strength and allows you to add length, so a handful of fibres can become a length of thread, string, or rope. It’s not surprising that thread, the making of thread, and the tools to make thread, turned up in tales and myths.

The Greek Fates, or Moirae, were usually depicted with yarn and its tools: Clotho spinning yarn on a spindle, Lachesis measuring the length of a yarn or a life, and Atropos snipping it off when the end was reached. A simple craft, but recognised as being intrinsic to life and living even then. The idea of a human life equating to a thread in a tapestry, weaving in and out, is a very old one. The Norns, the northern fates, are also spoken of as spinning and weaving men’s fates too.

Unsurprisingly, spiders have been associated with yarn production more than once – there is the myth of Arachne from ancient Greece, and that of Spider Grandmother from the Navajo and other Native American traditions. The Arachne story is interesting, in that it seems to be accepted that mortals can exceed the gods in skills and artistry; just don’t boast about it where they can hear you!

The tools that make the yarn turn up in our tales, too.

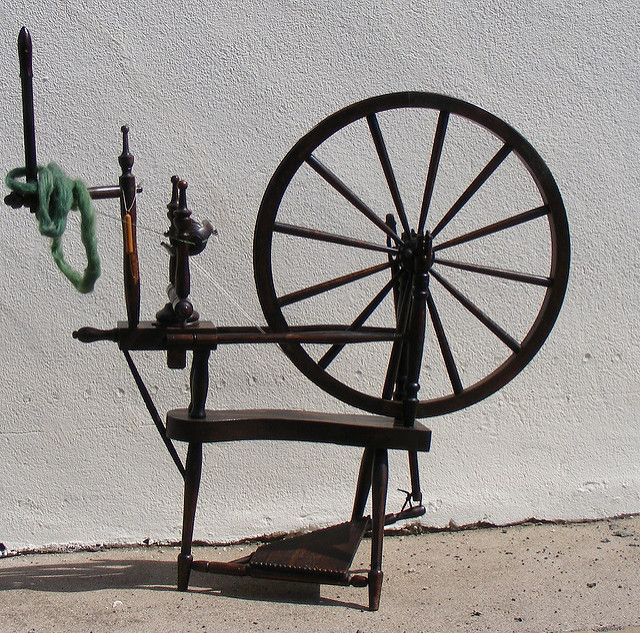

Take ‘Sleeping Beauty’, for example. She pricks her finger on a spindle and falls asleep. So far, so straightforward; most people take this at face value. As a person who spins in public frequently, one of the most common questions I get asked is, ‘Where is the spike?’ And this is where the passage of time comes in – spinning wheels have changed. Most fairy tale, and more modern, wheels look like this:

Now look at this:

This is a great wheel, the earlier form, and you can stab yourself on this thing very easily. An accidental jab from the spike/spindle in the days before antibiotics and you might sleep for longer than a century.

Spinning wheels came relatively late to yarn production. They appeared in Europe in the thirteenth century, having been invented in India a few centuries before, and in use in the Islamic and Chinese worlds before they came west. Before the wheel, everything was spun with a simple spindle. Everything. Clothes, furnishings, and ships’ sails. Lots of yarn was needed, and this is why unmarried women became ‘spinsters’. Any woman (or child or man) who wasn’t doing something else would spin. Some common women’s work could be done hands free, so spinning could be done simultaneously.

Spindle whorls have been found from all periods of human history, and in nearly every culture. They are one of our most ancient tools, made of stone and bone, wood and ceramics, and are often patterned. Could a spindle make a spell as it spins and falls? Mine sometimes do.

And the woman’s side of the house — the female line of descent — was referred to as the ‘distaff side’. The distaff was the stick or pole used to hold the linen or wool out of the way while it was being spun. Oddly enough, a floor-standing distaff looks much like an upside down broom, and it would make an excellent flying steed for a witch.

Spinning straw into gold, raw flax straight from the fields resembles straw as much as anything. Then it’s rippled, retted, broken, scotched, hackled, spun, and woven. At the end of this you have a valuable piece of linen cloth, at its finest worth a considerable amount of money in a pre-industrial society; worth gold, in fact. The tale of ‘Rumplestiltskin’, and its variations, all deal with the basic exchange of a first-born child for services rendered and the subsequent change of mind by the mother, but this straw into gold idea slips in too.

Nettles can be made into a fabric much like linen, and is processed in a similar fashion, so the tales that tell of silenced princesses stinging their hands as they pick and spin nettles to make shirts for twelve avian brothers have a grain of truth. Those stories have been remembered by people who knew that nettles could be made into fabric, but not exactly how.

© Freyalyn Close-Hainsworth https://www.flickr.com/photos/freyalyn/30158947214/

Weaving is nearly as ancient as spinning itself, but oddly, knitting came surprisingly late, and cannot be traced back further than the eleventh century in Egypt and the Near East, and considerably later in Britain, but both of these deserve their own consideration.

Spinning is an utterly basic human need, but now it’s nearly all automated and industrialised and not everyone knows their friendly neighbourhood handspinner. We are here, though. There is a reason why ‘spinning a yarn’ has more than one meaning.