The life of the shanty is a fascinating example of how elements of a music genre can evolve to match its environment.

The exact origin of the shanty may not be known, but what is certain is that it was a product of its circumstances. It first appeared as a distinctive song type in the 15th century, aboard the sailing ships of Europe, where the working song ensured that sailors could coordinate to complete physically intensive tasks, such as hoisting the sails for departure. This was also the period when squared sailed vessels supplanted the oared galley as the premiere form of waterborne transport. The first shanty attested in print appears in The Complaynt of Scotland from 1549, a Scottish book published during the conflict of the Rough Wooing. The text describes how, as the sailors started to haul up the anchor, they sang the following shanty:

“Vayra, veyra, vayra, veyra,

Gentil, gallanntis veynde:

I see him, veynde, I see him

Pourbossa, pourbossa.

Haill all and ane, hail all and ane;

Hail him up til us, hail him up til us.”

The location of the anchor is addressed by the singer throughout and the calls are intended to encourage the sailors. The multiculturalism of the songs are apparent even in this early form of the shanty, illustrated by the use of the word “Vayra”, which most probably derives from the Spanish word vira – a command to hoist or heave. The 16th century was also the period of expansion for the Spanish colonial empire and the growth of its nautical influence, which in turn intensified the spread of the language.

The “Come all ye’s” was a class of sea song that was printed for street singers, and afterwards sold at the ship yards by entrepreneurs. These songs were already a prominent feature during the late 1500’s. The composers of these tunes usually sought to capitalise on notable naval events, such as battles, and they were rushed out to market as quickly as possible. The name is derived from the introduction that was commonplace among these songs: “Come all ye gallant sailors bold, and listen to my song.” These commercial creations were one source of inspiration for the sailors and their musical creations.

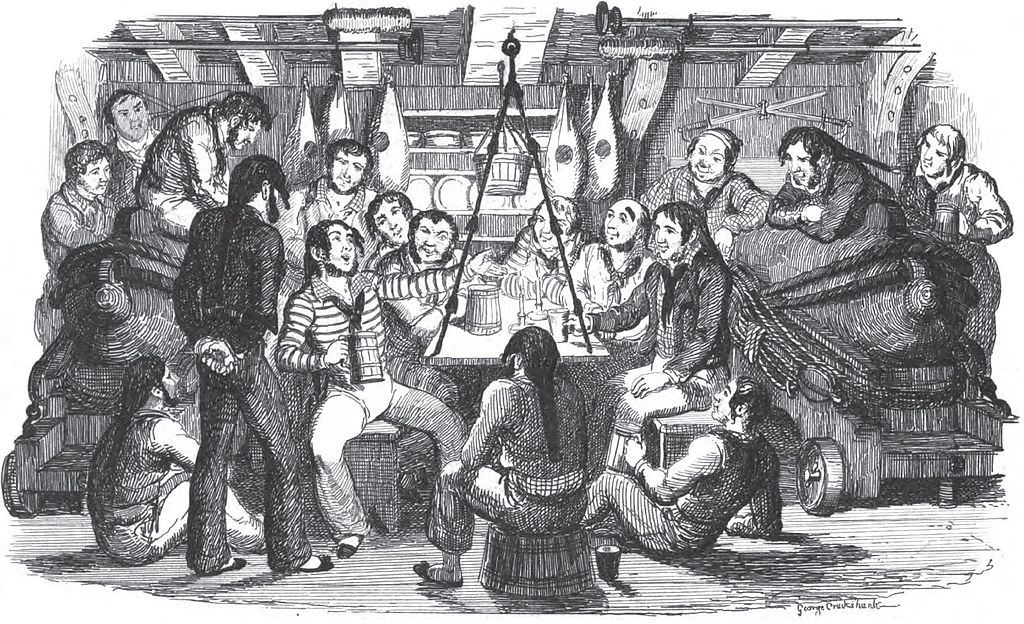

The heyday of the shanty would be the 19th century, when sailing ships were forced to match the pace of steam powered vessels; as a result the songs were more important than ever because it could get every ounce of power out of a crew. Shanties could function as an indicator of the sailor’s mood as well, because when silence reigned it could indicate the possibility of a mutiny. This century was also a period when the opportunities for African American sailors increased and the mix of songs mirrored the multicultural nature of the crews. Often a song would be inspired when a tune was overheard while a crew was in a foreign port, which added to the eclectic nature of these songs. Songs would be exchanged across cultural lines, even though the words may not have been intelligible to the lender, it would be sung if the tune was infectious. This would lead to some shanties containing words with no real meaning because it had been misheard or derived from another context.

As the shanty evolved during the 19th century, the songs became more specialized, to fit in with specific tasks: the two main types being hauling or heaving songs. Hauling songs had to coordinate sporadic actions, such as hoisting the topsail. A good hauling song would ensure that everyone in the work team would pull the rope at the same time and would also contain pauses for workers to catch their breaths. Hauling songs could be further subdivided: there were halyard songs (otherwise known as long-drag songs), short drag songs and pumping songs. Heaving songs, on the other hand, would be sung while at the capstan, a device that raised the anchor of a ship. A slow, steady beat was thus an important feature for this arduous task.

A major attraction of shanties were the morale lifting aspect of the ditties; they could make time go faster when the crew were busy with manual tasks and could inject humour into an otherwise dull day. A shantyman with an encyclopaedic knowledge and the ability to improvise was, as a result, a valuable asset on a ship and they were treated as such – they enjoyed lighter duties and could even be rewarded with extra rum. In their duties, they served as collectors of songs, and their knowledge were deemed to be as good as a number of extra hands on deck. A former singer, reminiscing about bygone days in 1939, described it as follows:

“The solo is sung by the shantyman sitting on the capstan head … The shantyman sits there and does nothing, while the crew, walking around the capstan, are singing.”

The singer had, as can be seen from the description, the envious position of being able to relax while others worked, but they still had to be skilful enough to entertain and motivate his fellow crewmates with their enthusiasm and musicality.

Steamships would ultimately be the invention that ushered in the end of the sea shanty, because the manpower and coordination needed for tall sail ships wasn’t a factor on the steam powered crafts. Therefore, by the turn of the 20th century, the sea shanty wasn’t the common feature that it once had been and shifted to the folksong genre, to be enjoyed on its own merit by appreciative future generations.

Shanties, as we’ve seen, were the glue that bonded the individual crew members together and allowed them to move as one. Although the term shanty was only first used in 1869 to describe this type of song, they had in fact been used for centuries before that, and would endure for long after that as an art form, preserving an aspect of the age of sail.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

James Fenton. 2007. ‘Songs of the sea.’ The Guardian.

Ted Gioia. 2006. Work Songs. Duke University Press.

Ben Johnson. Sea Shanties.

Sharon Marie Risko. 2015. 19th Century Sea Shanties: from the Capstan to the Classroom. Cleveland State University.

Matthew Sabatella. ‘Shenandoah: An American Folk Song.’ Ballad of America.

B. Whall. 1913. Ships, Sea Songs and Shanties. James Brown and Sons.