Poland is a country where the diversity and presence of textile traditions in folklore derives from the country’s long and complicated history. Textiles have always been present in everyday life in all kinds of underwear, linens and clothes. In decorative forms, it hung on walls, windows and doors, and covered beds, seats or even horses’ backs. Handicraft weaving had social importance too, as it usually united people of the countryside who crafted together.

The region where Poland is today was firstly inhabited by Slavic people in the 5th century AD. The country was established in the 10th century. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance it was exposed to Germanic, Latinate and Byzantine influences and resulted in an idiosyncratic cultural nation having its own features enriched by different cultures. In the late 18th century Poland lost its independence and for the next 150 years (to the end of the World War I) was divided and ruled by Russia, Austria and Prussia. Despite the often harsh and changing political landscape, Polish artisans have been able to maintain and adapt the handmade textile traditions of the past so that today they remain a significant aspect of Polish culture.

The materials for folk textiles were acquired from farming which, with the Polish climate, meant linen, wool and, rarely, hemp. They were dyed in natural colourings made from plants and minerals. Since the patterns used for textiles differ, they can be divided in three groups: pasiaki, kraciaki and multi-patterned.

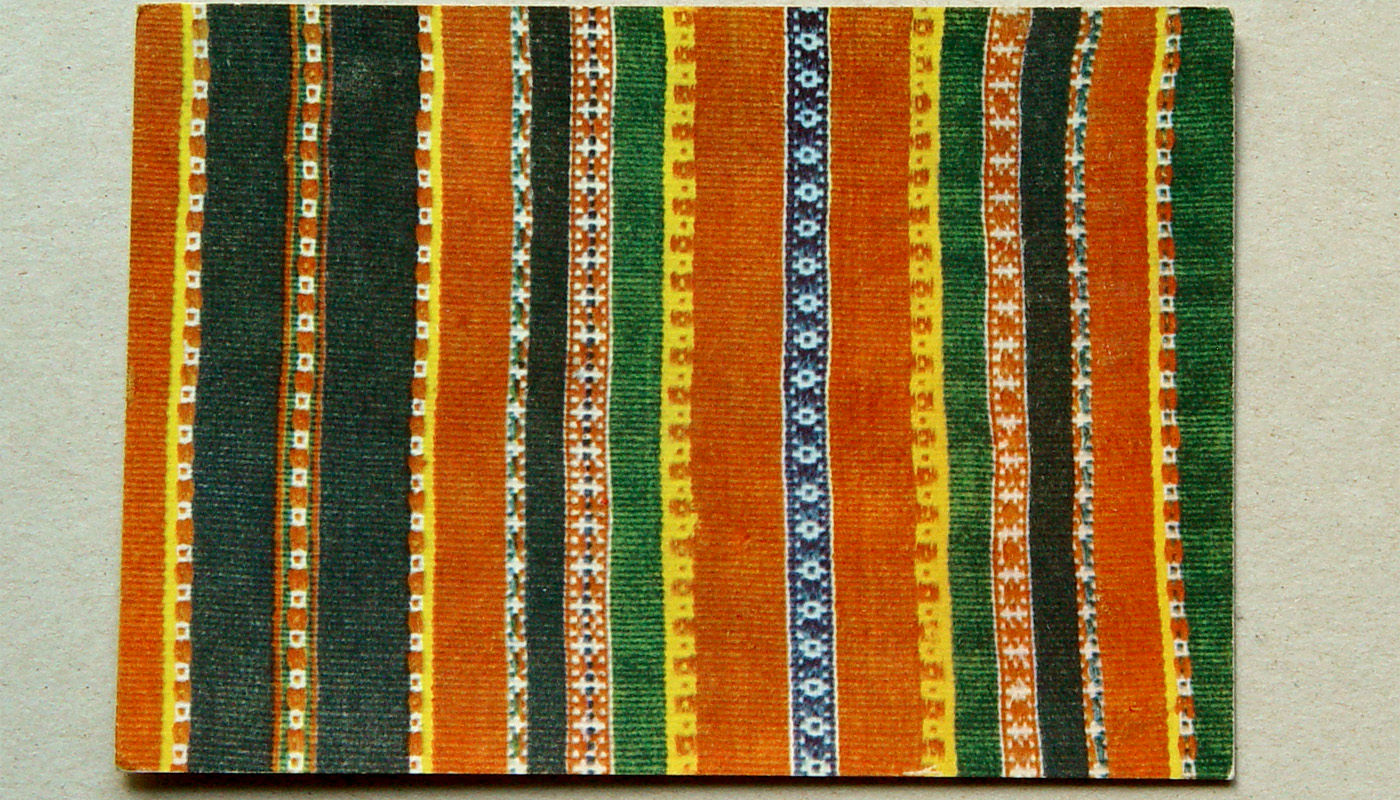

The oldest and simplest are pasiaki. Their name comes from the pattern itself: pas in Polish means a stripe. Pasiaki were woven of pure wool of high pile and originally were rather modest, combining only two or three colours in narrow stripes (usually red with black or white and sometimes blue). They were known and made since the 11th century. The 19th century gave them new life with development of dyeing and so the number of colours increased to over twenty. Wool-linen pasiaki were usually used to make women’s clothes, but they also had a common use as kilims – rugs hung on the wall – or as a bed cover.

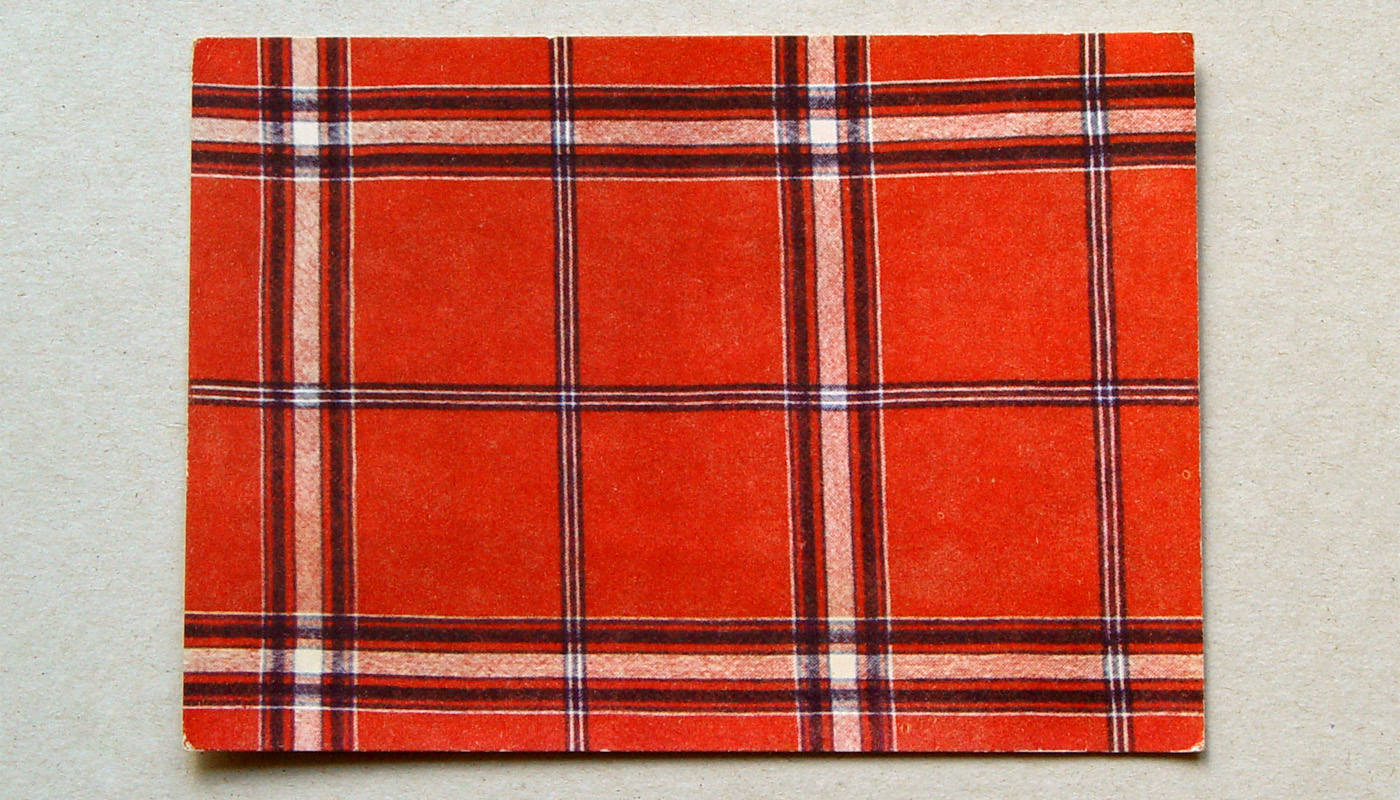

The second kind, kraciaki describe checked weaving on linen that can be also combined with cotton or wool. Commonly applied colours for check were red, black and blue. Depending on the textile function, the background could be black (for skirts) or white (for bed linen).

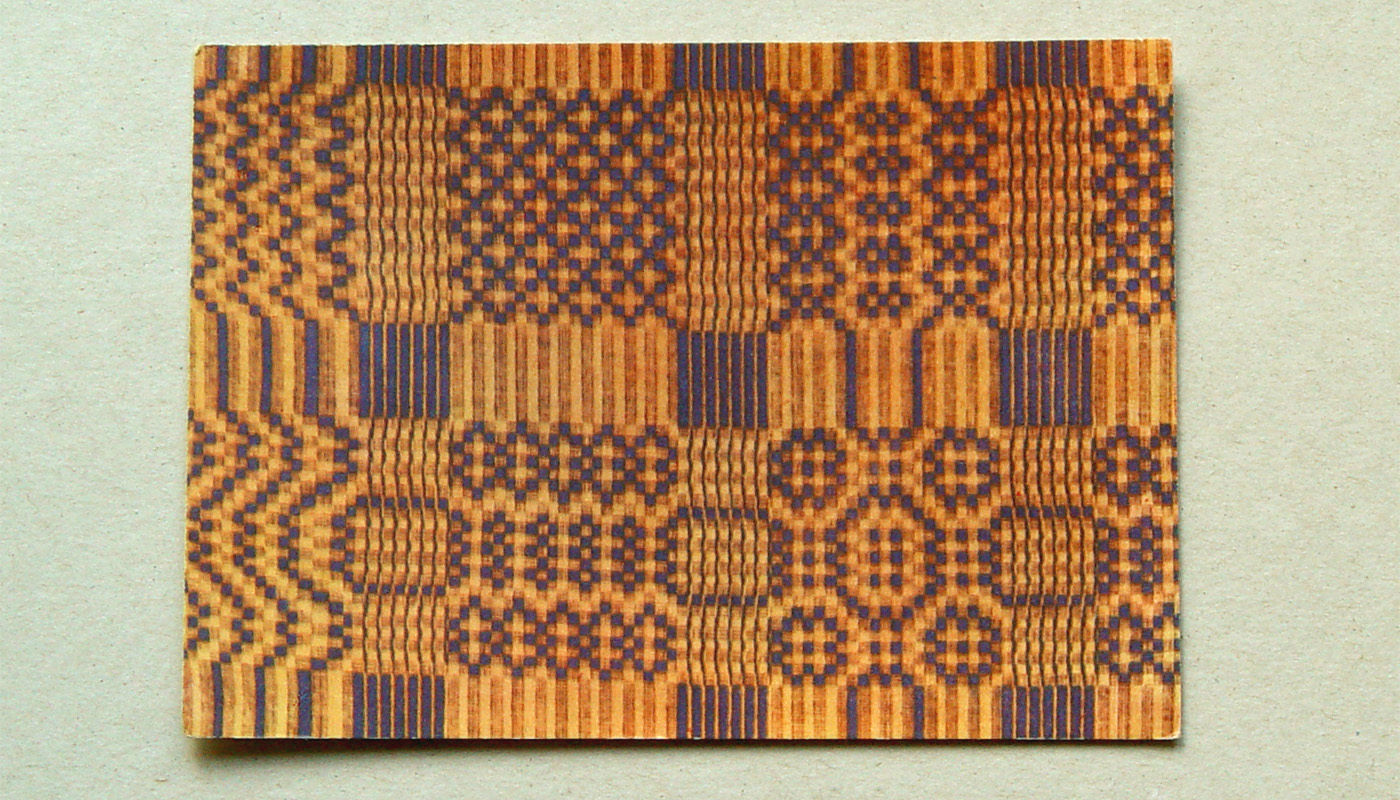

The third category of folk textiles was not defined in terms of shape’s regularity. Multi-patterned textiles served mostly as decoration, such as kilims made in tightly interwoven warp and weft technique. The most famous of them, called double warp carpets, come from the northern-eastern part of Poland from 19th century. These are double layer textiles with patterns, made of wool in two colours, where the reverse side is chromatic reversal of the right side. They are manufactured with the use of canvas weave on hand looms with tread and four harnesses and the pattern is handmade with the use of woollen selvage. This technique allows the ability to apply the whole variety of motives in the composition, including weaving figural scenes of narrative character.

Originally crafted by professional artisans for wealthy families, they gained interest and recognition that led to peasants adapting this technique. These textiles were precious and as such they were considered as family treasure inherited by generation after generation.

Apart from the three most important types of pattern described, printing was also commonly used as a decorative technique on skirts, shawls and aprons, especially in 19th century, after peasants were granted the freehold of land. Unfortunately, soon after that, small manufacturers and dyers had to give way to growing industry, and traditional methods disappeared from use. Folk textiles with printed patterns were usually in two colours, most often white on blue, obtained by batik dyeing technique.

Repercussions of typical peasant culture are the distinguished characteristics of the traditional dress of Poland. Polish folk costumes vary from region to region. Peasants’ dress became distinct from that of other classes beginning in the 15th century. Dress quickly became a symbol of group values. A phenomenon typical in Polish folk culture was the borrowing of elements from higher classes, seen in folk dress with rich baroque detail. The peak development of folk dress in many parts of Poland occurred when peasants were granted the freehold of land. Festive and ceremonial dress acquired new cuts, colours and accessories and was very different from everyday’s attire. Majority of clothes, underwear and shoes were home crafted, following traditions of a region.

In general, Poland may be divided into three regions in terms of different materials and design for folk dress. Dress from south-eastern Poland is based on bleached homemade linen or hemp canvas and woollen textiles. Linen shirts and skirts are decorated with one-coloured embroidery, while other multicoloured embroidered pattern, called parzenica is vastly present on trousers or overcoats made of tucked wool. These are to this day worn by mountaineers in Podhale, which is the only part where folk costumes didn’t disappear from everyday life. This is also the region where weaving and felting is associated with men.

A huge variety of colours characterise folk dresses in the central part of Poland: Masovia and Podlasie. Pasiaki are the most popular pattern on dresses, and broad shawls hung from the shoulders, called zapaski, are made of woollen homespun fabric. The region of Łowicz is especially well-known for women’s folk costume. These dresses quickly evolved from the second half of 19th century, when they were plain red and worn with red and white striped zapaska. Then more colours were added, starting with yellow and orange, to the point where the stripes had all different shades with a dominant cold green. At the same time, the cut of the dress evolved and widened, resulting in a skirt that was an impressive five metres in circumference! They became so heavy that they must have been attached to vests in order to stay on the waist. Finally, the dresses were made shorter so that they could have an expensive velvet ribbon with colourful embroidery at the bottom. When the dress changed, so did the zapaska, stacked in folds (ironed with hot bread!) to keep stripes symmetrical and coordinated with the skirt.

In north-western Poland homespun textiles vanished early on, and urban fashion had the highest impact. However, dresses succeed in retaining folk and regional character. The style is adapted from bourgeois, noble or even Western European costumes. The same characteristics apply to representative dress from Krakow despite its southern location. As Krakow is the cultural hub of Poland (it used to be a capital), its regional dress became a national costume and a symbol of the fight for freedom.

All the Polish folk costumes are rich with embellishments: embroidery, braids, laces and even jewels. At first they played a protective role on seams and edges, but with time they evolved into decoration and a social and material status symbol (the wealthier the woman, the more red corals on her neck).

There are no special wedding folk dresses. For this occasion complete festive dress is worn with special accessories, informing about the role played in the ceremony – wreaths or crowns for women and peacock or rooster feathers for men’s caps.

The diversity and richness of Polish folk textiles may be well described, but it is worth being seen in real life. Come to Poland, go to the countryside on a festive day and you will be enchanted. A great number of folk museums preserve and document all crafting traditions mentioned. Folklore is living part of Polish cultural identity.

Many thanks to Olcha Grochowska for the English translation.