What unites bikers, punks, feminists and sewing? Scott Malthouse explores the social history of battle jackets.

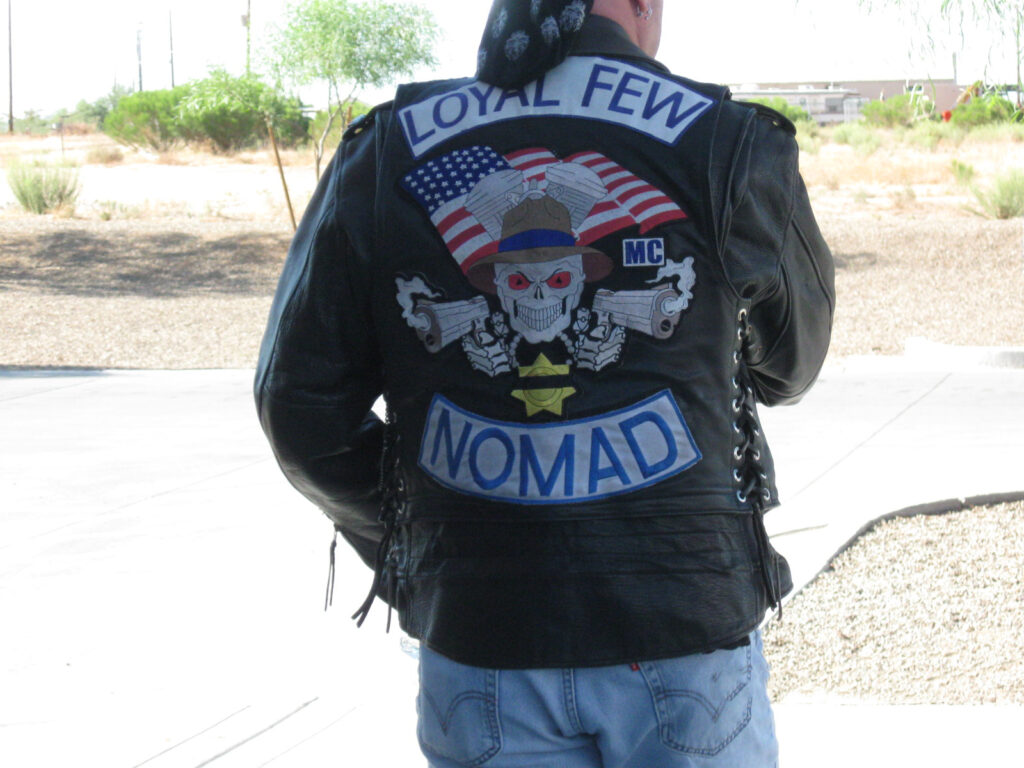

You’ve definitely seen a battle jacket. Maybe it was on the school bus, where a kid enthusiastically pointed out her favourite new patch, or outside a gig venue where hundreds of denim jacket-clad punks gathered waiting for the doors to open. Maybe you’re even wearing one right now. Battle jackets, also known as battle vests or cut-offs, are generally made of denim or leather, sleeveless or with sleeves, and covered with an array of band patches of all shapes and sizes, along with studs, safety pins and buttons. These music-adorned garments have been a fixture of the metal and punk scenes since the 1970s, after they were co-opted from the culture of American biker gangs, who wore them as a form of identification. But why have battle jackets managed to stand the test of time, long after punk and metal hit the mainstream in the 70s and 80s?

“A battle jacket is your identity; you let people know who you are, what bands you like, your politics, and more recently, even your hobbies and fandoms,” says Emily Romig, curator of the online Battle Jacket Museum. “My jacket acts like a form of emotional and social armour. I have one I wear to protests, and one I wear to shows, for instance. They let others around me know a little bit about who I am without even speaking to me.” A cursory scroll through the Battle Jacket Museum website’s gallery shows how true this is. A bride throws up the metal horns, her white veil draping over her jacket. A camo jacket is seen covered in, not band patches, but anime and occult references, while others don their jackets to make pointed political statements. They have gone beyond just what bands you may like, to people literally wearing their personalities and philosophies on their sleeves.

“I see women and femmes taking so much more ownership of the tradition now than in past decades. I think the jacket has also transcended strictly music-related spaces and themes, and become pure expression,” says Romig. While the punk and metal cultures of the 80s could be considered as more of a boys club, that symbol of identity is now being embraced by marginalised groups who are proud of who they are, just like metalheads who wear them show pride in their love for Iron Maiden or Anthrax. It’s a canvas for people to tell their own stories and have others acknowledge them.

This form of folk expression is nothing new. Go back to Japan in the early nineteenth-century, the Edo period, where firefighters wore special coats called hikeshibanten. When reversed, these fireproof coats were embroidered with popular folk tales of heroes overcoming dangerous odds, just like the firefighters themselves. This expression of community through textiles has occurred throughout history, something that Romig was conscious of in her first forays into the battle jacket world.

“When I first started making my own battle jacket, it reminded me of a lot of the traditional fibre arts I’ve seen that also tell a story, such as quilting or embroidery. Mine is such a complicated assertion of who I am, almost as if it’s a set of tattoos I can take on and off at will.”

This form of folk art is important, particularly in times as politically and socially charged as these, but battle jackets are somewhat overlooked despite being clear barometers of social change. This is why Romig does this — to tell the stories that aren’t getting told.

“When I collect a photograph of their jacket, I collect a part of them so that not only people on the street can see it and know who they are, but anybody who visits the museum online as well.

“That kind of intensely personalized DIY is so appealing to me, and with each jacket photo I collect, I’m able to piece together a part of art and social history that hasn’t been documented nearly as much as it should be. It’s so difficult to curate actual physical garments, especially something like a battle jacket that sees so much use and wear in its lifetime. Photographs seemed like the obvious way to go instead. That way, I can incorporate a person’s story along with their jacket.”

From their inception as communal livery for bikers, battle jackets have provided a way for people to subvert the norm, to live outside of mainstream and be recognised as part of a community of like-minded individuals while still maintaining individuality. But importantly, these aren’t off-the-shelf items (despite some high street retailers attempting to profit from this subculture) — they’re crafted artefacts, meaning no two are ever the same.

‘Jazzman’, whose vest is proudly on display on the Battle Jacket Music website, probably sums this up best:

“My jacket is kind of like a second skin to me and it makes me feel so much more confident. If anyone comes up to talk to me, it’s usually because they like my jacket. Or it intimidates people that I don’t want near me. It’s a sign that I believe I can make a difference just by being who I am.”

If you want to learn more about battle jackets, pay a visit to the online Battle Jacket Museum.

References

Emily Romig, Battle Jacket Museum