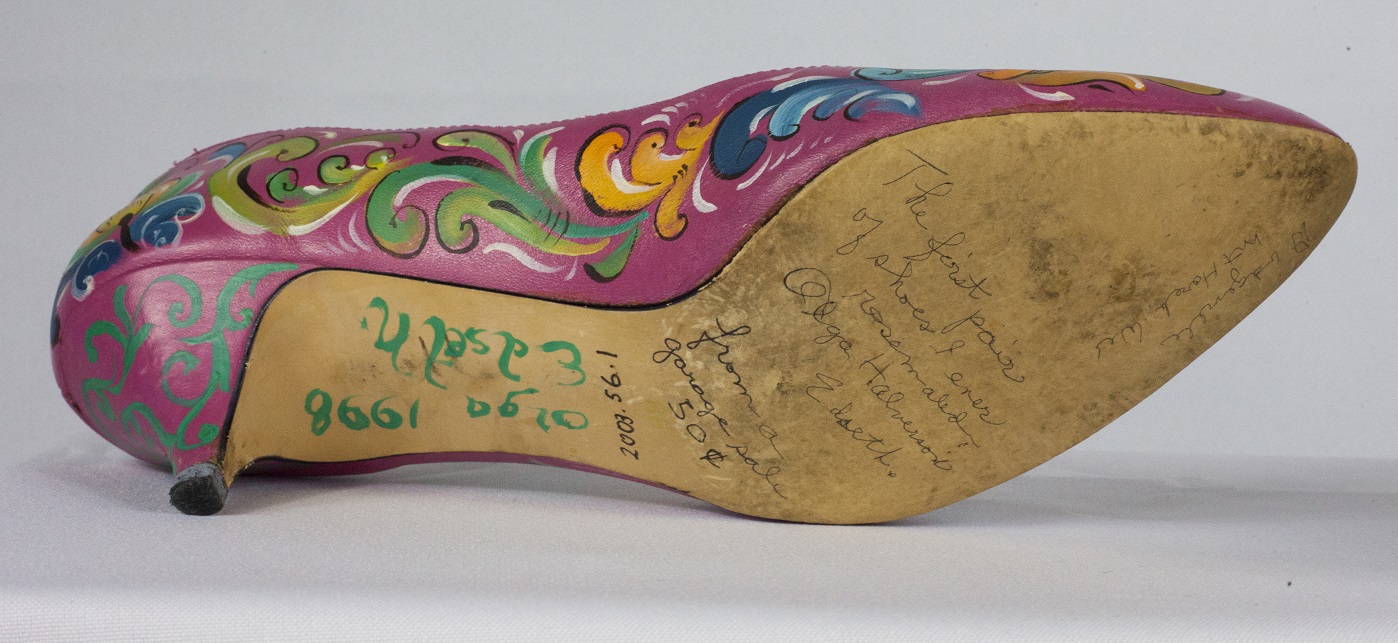

In America’s Dairyland, expressing one’s ethnic identity sometimes means not only participating in the revitalization of a folk art but transforming it into a fashion statement. In 1998, Mount Horeb, Wisconsin, resident Olga Edseth (1914—2012) visited a garage sale in her nearby hometown of Dodgeville. While at the sale, she came across a pair of vibrant hot pink leather pumps. After paying fifty cents, Edseth brought these size eight shoes home and transformed this symbolic footwear of the professional 20th century woman into a form of heritage on the go by applying her award-winning talent in the Norwegian folk art painting style of rosemaling. Across the sole of the right shoe, Edseth, in her distinct cursive, declares the now ethnic fashionwear as being, “the first pair of shoes I ever rosemaled.”

Rosemaling developed in 18th century Norway and flourished throughout the 19th century, spreading across the nation developing distinct motif variations reflective of county preferences and painting techniques. A fusion of Nordic carving traditions, European and Renaissance geometric painting styles, and Baroque scrolls, rosemaling features two-dimensional stylized floral patterns accompanied by Rococo C-stems, tendrils, and acanthus leaves. Rosemaling commonly draws from a limited color palette highlighting earthen shades of reds, blues, yellows, whites, and greens. Originally applied to the interior of churches, rosemaling eventually came to be a significant design element of Norwegian households, bringing color and warmth inside during long cold winters. Rosemaling later made the leap to flat wooden objects like signs and cutting boards as well as the curved edges of bowls. And in Mount Horeb, to a pair of hot pink pumps.

As Norwegians emigrated by the hundreds of thousands to North America during the 19th and 20th centuries, they brought rosemaling with them in the form of heirloom objects and learned skills. Folklorist Janet Gilmore observes that today rosemaling functions as a distinct symbol of Norwegian-American identity. This symbolic connection to a sense of Norwegian-Americanness is particularly pronounced in Mount Horeb, located approximately twenty-three miles southwest of the state capital of Madison. Although not initially settled by Norwegians, Mount Horeb began to see an influx from this Nordic state beginning in the 1870s. The sense of heritage began to take off with the open-air folk museum, Little Norway, which drew tourists to visit an idealized reconstruction of a Norwegian immigrant farmstead, complete with a replica of the Stavkirke originally constructed for the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition. During the 1960s and ’70s, Mount Horeb experienced a Norwegian revival with the annual production of the “Song of Norway” musical and a proliferation of rosemaling from local artists covering surfaces throughout the community. One of these artists who contributed to colorful revitalization of Mount Horeb was Olga Edseth.

A self-taught artist, Edseth’s rosemaling spanned over sixty years. In recognition of her artwork, the Sons of Norway presented her with an International Heritage Award. Norway was always close to her heart, growing up in a heavily Norwegian family and making numerous trips to her ancestral homeland. According to Brian Bigler, collector and volunteer coordinator at the Driftless Historium in Mount Horeb, Edseth was, “very Norwegian in her talk and everything…she still had an Old Country accent. She talked kind of in a Norwegian accent.” Bigler notes that Edseth:

“would not sell any of her work and it was all of her family’s, so her house was completely filled with objects. And I think she got so interested in rosemaling that she just couldn’t find enough of the next thing to put rosemaling on, so she had everything from soap bottles to ceramic vases to everything covered with rosemaling. But she did a beautiful job of it. So she’s a great example of that, going completely bonkers over something she felt she was losing from the Norwegian identity, it was going to be lost, generations were dying, and she had seen that happening.”

Perhaps, then, it was only natural for Edseth that when a pair of hot pink pumps crossed her path, she found an opportunity to push the medium into a vibrant and mobile direction, a direction recognized as worthy of preservation and display.

In June 2017, the Mount Horeb Area Historical Society re-opened its doors after several years of major reconstruction and renovation as the Driftless Historium. Although portions of the historical society/museum were still under construction, the site premiered its first temporary exhibit, “Creators, Collectors, and Collaborators.” The objects on display range from trunks and snuff boxes brought by immigrants, to a locally produced Norwegian Wafer (Krumkake) Iron, Norwegian folk costumes, and hand-crafted troll dolls. Working with a group of University of Wisconsin-Madison students led by Dr. Ann Smart Martin, I assisted in drafting the interpretive labels in the exhibition.

One section of the exhibit, “Heritage Memorialized”, focuses on how mid-to-late 20th century artists and collectors revived traditional forms of artistry and imaginatively memorialized their ethnic roots. “Heritage Memorialized” emphasizes two distinct components: 1) individual artists performing their ethnic identity through material culture, and 2) the strong presence of rosemaling and Norwegian-American folk art. Three objects painted by Edseth are on display in this exhibit, with her shoes positioned to grab visitor’s attention. Those pumps speak to the transformative potential of rosemaling on everyday objects as well as the personality of the artist.

Bigler notes that Edseth approached the last decade of her life, she was very intentional in her selection of artwork to donate to the Historical Society for future display. He states that:

“I’ve noticed that with older people, they’re very sentimental about their things, then all of a sudden there’s a period of letting go and then there’s a re-attracted period. And she got into the period of letting go, but what she picked to represent her she did on her own, we didn’t go in and do it, which I find interesting. And so she picks a very formal basket that has a good story. And the first plate we already had. But then she picks this quirky set of shoes, and to me that just says this is her personality – something really refined but she can also be very quirky, and she wanted that to represent her. It’s totally what I believe that she did that, [that] thought pattern went through her head, that this is her legacy.”

The idea of self-selecting one’s legacy for display was important to Edseth and is a value reflected in the Historium’s current collecting and curatorial practices. In the past the Historium not only selected artwork from individual artists and collections but commissioned pieces of art. Bigler summarizes the shift by stating that:

“If you have a piece of art you want to give us, what best represents you, do you think, for future generations, what do you want people in the future to see you as. So for Olga, apparently, [it] was a pair of rosemaled shoes, but a very nice refined basket as well.”

This dedication to representing Edseth’s legacy through displaying her artwork becomes apparent at the exhibit. Visitors have the opportunity to view the distinct components of the playful personality noted by Bigler, but see the importance of rosemaling and local heritage as guests view the developing practices of a rosemaler through comparing three pieces spanning her artistic career. Nearby is a colored image of an elderly Edseth sporting a bunad—a traditional Norwegian folk dress—rich with blue and red fabrics. Standing in a grassy yard, she also wears a warm smile, one which not only greets you as a friend but invites you to enjoy her passion for Norwegian and Norwegian-American art, and maybe to even share a laugh with her over a pair of rosemaled leather hot pink pumps.

References

Bigler, Brian. Interview. October 11, 2017.

DeMello, Margo. Feet and Footwear: A Cultural Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2009.

Dregni, Eric. Vikings in the Attic: In Search of Nordic America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Ellingsgard, Nils. Norwegian Rose Painting in America: What the Immigrants Brought. Decorah: Scandinavian University Press, 1993.

—. “Rosemaling: A Folk Art in Migration.” In Norwegian Folk Art: The Migration of a Tradition, edited by Marion Nelson, 190-237. New York: Abbeville Press, 1995.

Fapso, Richard J. Norwegians in Wisconsin (Revised and Expanded Edition). Madison: The Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2001.

Gilmore, Janet. “Mount Horeb’s Oljanna Venden Cunneen. A Norwegian-American Rosemaler ‘on the Edge.’ ARV Nordic Year of Folklore, 2009(65): 25-48.

—-. “Restless Spirits on the Driftless Landscape.” Vernacular Architecture Forum, 2012:34-55.

Leary, James P. “Norwegian Communities.” In Encyclopedia of American Folklife Volume 3, edited by Simon J. Bronner. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2006.

—-. “Scandihoovian Space in America’s Upper Midwest: Impersonating Ole and Lena in the Twenty-First Century.” American Studies in Scandinavia 44, no. 1(2012): 7-28.

Johnston, Lucy (Lucy Anne). Shoes. New York: Thames & Hudson; V&A, 2017.

Lovoll, Odd S. The Promise Fulfilled: A Portrait of Norwegian Americans Today. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

—-. Norwegians on the Prairie: Ethnicity and the Development of the Country Town. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006.

—-. “Introduction.” In Wisconsin My Home: Thurine Oleson As told to her daughter Erna Oleson Xan (Second ed.). Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. xi-xviii, 2012.

—-. Across the Deep Blue Sea: The Saga of Early Norwegian Immigrants from Norway to American through the Canadian Gateway. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. 2015.

Mount Horeb Area Historical Society (a). Creators, Collectors and Communities: Making Ethnic Identity Through Objects An Exhibition Catalogue. Mount Horeb, Wisconsin: Mount Horeb Area Historical Society. 2017.

—- (b). “Exhibits.” Accessed: November 21, 2017. http://www.mthorebhistory.org/exhibits.html