‘I can’t describe to you what it feels like to hold your own death in a needle in your hands,’ says the childless Molly in Tatterdemalion. ‘I got used to it, though, walking all those miles through the grassland, the marsh, the evergreen wood, following the pricks of that needle against my chest, where it hung from a string. It was comforting, in a way, to see it there, silver and glistening. No mystery, just sharp and in my care. But the cost of slipping and falling was high. My feet became steady and very slow.’ Molly has made a bargain with Niss, the Wild Folk woman who lives at the edge of her town in a hen-shaped wooden hut. Niss is a tiny woman, gnome-like, protector of the forest and of fertility itself, and she demands that the women of the village bring her baskets full of eggs every full moon.

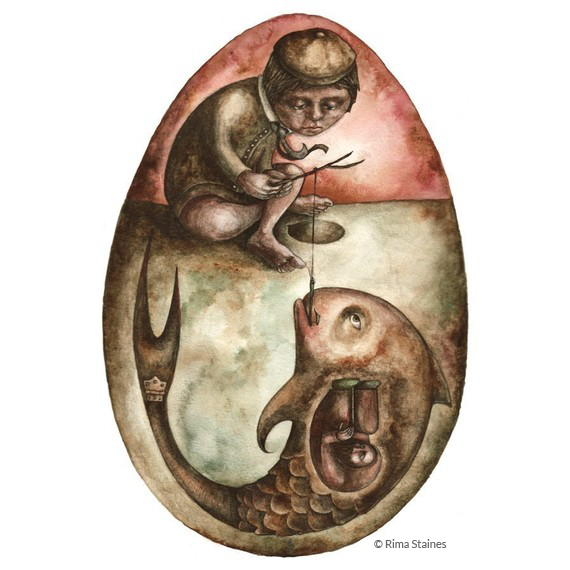

When Molly, desperate for a baby, asks if Niss can help cure her barrenness, the little woman makes her choose between two eggs, saying, ‘One has in it your death, preserved in the tip of a needle. The other, a life that you could carry. You must pick an egg without knowing which it is. Then you must crack it. If it is the one full of new life you must swallow it whole. You’ll grow like any other pregnant woman, and give birth to a child with ten fingers and ten toes, though his nature I cannot speak to, nor to the possibility of a tail. If you crack the egg and find in it a needle, you can either politely return it to me, and go back home, and forget all of this business, or you can follow it. That needle with your death in the tip is a compass needle and can be followed to a baby that must be dug up from the ground, a birth from the roots, perfect and growing as a seed. But if you break the needle, you will die, right there.’

Tatterdemalion, my novel with the magnificent English painter, Rima Staines, is rooted deep in folkloric ground. I imagine that ground like rich humus in a very ancient forest; all the stories both Rima and I have read and heard and taken in over our lifetimes, since we were small girls, are the thick bed of leaves underfoot. Tatterdemalion is in fact a post-apocalyptic novel, but it takes its tone and spirit from the folklore and myth of Old Europe. This is in part because Rima’s work is born right from a medieval hearth-fire somewhere between Bavaria, Poland and Siberia, in part because I can’t seem to write anything that isn’t informed by the structures and sensibilities of a folktale, and also because when my words found Rima’s paintings, this was their common ground. There was no other way for the novel to root and grow, except from these many layers of storied humus.

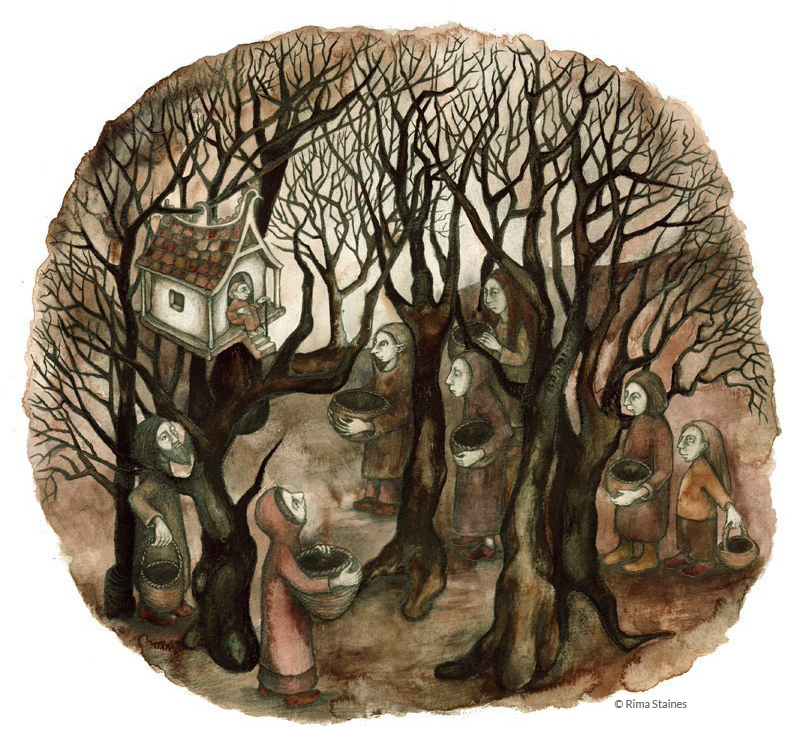

What’s wonderful about the way Tatterdemalion came into being is that nothing within the novel is a straight re-telling. None of Rima’s paintings (fourteen of them, painted over as many years in her career as an artist) illustrate specific stories, but rather they hint at pieces of the ancient and the folkloric inherent in our imaginations, and in the land around us: a woman with owl wings; a tiny grandmother in a henhouse in a tree; a creature with wheels; old women who look like roots. They reveal the sacred ground in each of our psyches from which folktales originally sprang, and remind us that a part of ourselves is very, very ancient. That part of ourselves is resonant with, and fluent in, the symbols, characters, archetypes, and motifs of the great collective story-matter of the human soul.

In the passages above, for example, imagery from the Russian folktale character Koschei the Deathless came seeping through the leaf-mould of my imagination and into Molly’s story. Not long before writing this chapter, I had read and memorized the Russian fairytale Tsarevna Frog, or Frogskin. Like many Russian folktales, the story involves both the Baba Yaga (who helps guide the prince on his way) and the demonic Koschei the Deathless, from whom Frogskin herself must be rescued. Koschei, however, cannot be killed like a normal man, because he has placed his soul, and therefore his death, in a needle, in an egg, in a duck, in a hare, in a wooden trunk in the top boughs of a giant oak tree, whose whereabouts nobody knows. The only way to kill him is to crack that egg and break the needle inside, which of course the hero of the story does (with the help of a duck, a hare, and a bear). As Elizabeth Wayland Barber writes in her book The Dancing Goddesses: Folklore, Archaeology and the Origins of European Dance, ‘the notion of keeping a life or soul inside an egg harks back to the ancient image of the egg as life capsule, and we have seen that a spell is broken by analogically breaking something brittle associated with it—here, either the egg itself or a needle inside it.’

Long after my reading of Frogskin, it was the death in a needle in a precious egg that haunted me. The image of the egg, that ‘life-capsule,’ around which so many creation myths the world over have centered, as the vessel of a soul; the image of the needle containing the soul itself, and therefore death. I did not try to reason through or psychoanalyze these images, though I am still fascinated by that needle in particular, and its association with Koschei. (Why a needle? Simply because it is small and mundane and therefore unexpected? Why such a feminine object, associated with sewing, with women’s work, with the sorcery of stitches?) At the time, I simply let those leaves settle down on the forest floor of my dreaming mind. The egg. The dangerous needle. In Molly, in her search for a baby, they rooted and unfurled again, new, but also old. A matter of fertility. A matter of new life, of transfiguration, of women’s magic, of stitching together hope again. The making of the whole novel had this quality about it: a sifting up through the leaves of the bones of old stories, these many small acts of transmutation. In the logic of folktale and myth, where shapeshifting is commonplace and humans, hares and hearths alike seem to have all of creation latent under their skins, this is as it should be. A book is an egg, a needle, a child dug up from the earth.

Tatterdemalion is deeply concerned with our relationship to the more-than-human world, to the state of the environment around us. It is concerned with the way the stories we tell ourselves shape the reality we live in. It imagines a future in which the industrial advances we’ve made in the last 200 years have collapsed, and what survives is the stories we tell. Rima and I have described the novel as a ‘folktale cycle’ because it uses the spirit of the folkloric to explore a possible future through the lens of the past; Tatterdemalion, in other words, imagines a future that is hopeful because it feels rooted in older ways and modes of being; because within its pages, it is possible again for a woman to become a barn owl, for an old lady in a tree to demand our homage, to dole out our deaths in needles if we do not live with humility and with awe.

Tatterdemalion is being published by the suitably revolutionary Unbound, but it needs your help to be born into this good world! (We are, as it were, in the process of digging the child up out of the earth …) The way Unbound works is that they have their writers raise the print cost of their book with pre-orders before going ahead with publication. Right now, our Tatterdemalion is on the brink of being fully funded, but we need your help to push it over the edge and to begin the journey toward bound-book publication! So, in the name of the folkloric, in the name of keeping our stories alive in the present moment in our artwork, as well as in the future, do come have a look at our Tatterdemalion here. There is a film, a wonderful excerpt, and some wonderful pledge levels, including a gorgeous, collectible leather-bound book, embossed with gold.

And finally, enjoy the beautiful fruits of this new #FolkloreThursday website! It’s an honor to share these words with you today, within the beautiful weavings of this excellent and storied resource. With much gratitude to the women of #FolkloreThursday for their wonderful work.