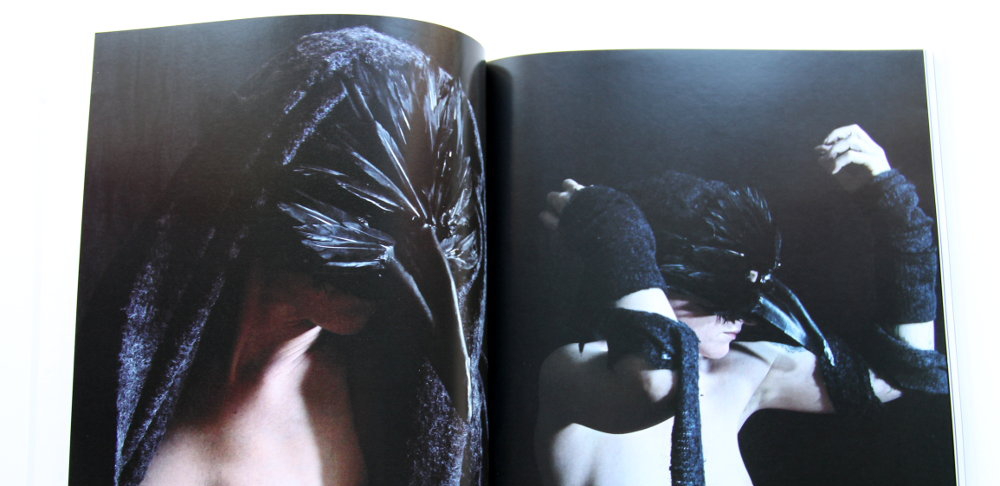

Paul Watson speaks to Dee Dee Chainey about the inspiration behind England’s Dark Dreaming, his second book of myth and folklore inspired artwork, available August 2018 (and available to pre-order now!).

Dee Dee: Great to talk to you today Paul. Firstly, congratulations on your second book! I’ll admit, I’m huge fan of your first — Myth and Masks — which touches on subjects like the English eerie, folk horror and psychogeography — so I was really pleased to hear that you’re releasing another, particularly dealing with such an important topic as the current socio-political upheaval in the UK, and its relationship with folklore.

Why did you feel the need to add your voice to the current discussion about the interplay between myth, folklore, landscape and today’s England with your new artwork series?

Paul: Thanks, Dee Dee. I had to tackle the subject of today’s England due to the continuing rise of the far-right, as well as its manifestation and amplification in things such as the Brexit referendum, as it so completely dominates what we see on the news and on social media.

While it is still only at a relatively minor compared to things that are happening elsewhere in the world, England is a country just starting to experience again the trauma of wide-scale socio-political upheaval at societal, familial, and personal levels.

And this trauma coincides with a growing concern about land and place, so using myth and folklore — which are older, deeper, stories about the land and our place in it — to explore the subject makes sense to me.

I’m not alone in this approach: the 2018 film ‘Armageddon Gospels’ written by John Harrigan and David Southwell’s Hookland Guide both use myth and folklore to explore the contemporary English socio-political landscape as well as landscape itself.

Dee Dee: Thinking of your accompanying essay, ‘Deep England’, is this a response, along with your artwork, to what’s being said by others, and are there any particular instances where you’ve felt the need to speak out against — or agree with — other people’s responses and opinions?

Paul: I wrote the original version of my ‘Deep England’ essay (the one linked to above) in the first few days of 2018. I’d been doing some reading over the previous few months as part of my research for the England’s Dark Dreaming drawings, and I’d seen the phrase Deep England used a couple of times, but never defined in any detail, so I set about doing so.

I was pleasantly surprised by the reception it got — very positive with the exception unsurprisingly of a couple of Neo-Nazis. I think it struck a resounding chord with what a lot of people were thinking about, but — in most cases — hadn’t analysed in detail.

One of the best responses was from the author Melissa Harrison who sent me a pre-publication copy of her forthcoming novel All Among the Barley (due for publication August 2018), and she had independently being researching the same area, and really cleverly fashioned that into one of the major themes for her novel. It’s a really great book, and I’d highly recommend it!

The essay is definitely a response to how the myth of Deep England is used to manipulate those of us who live in England, and usually not for the better. It’s got a long history — it’s been going on for about a hundred years now.

Fascism — before it has gained full power — uses infiltration and assimilation to try to gain a foothold, and we’ve all seen them try it online with the folklore and myth communities — the accounts that try to join in with hashtags such as #FolkloreThursday and then spew racist, nationalist, and white supremacist bile.

I’m a great supporter of the #FolkloreAgainstFascism hashtag that David Southwell invented. The aim is to stop the far-right from co-opting folklore as their weapon against vulnerable groups of people who are the subject of their bigotry. We can do this by being explicitly anti-fascist and preventing racists and nationalists from infiltrating our communities. We can do it, by standing up and calling out anything which — either by design or through ignorance — strays into the territory of the far-right and, by doing so, aids them.

Dee Dee: I’m very much looking forward to reading the extended version of the essay in the book!

Paul: Thank you! It’s about three times longer and includes a lot more detail.

Dee Dee: What is ‘Deep England’?

Paul: Deep England is a myth that is all-pervasive in England. It’s a utopian vision for many English people of how things were and should always be, particularly related to the English countryside. It’s an interwar idyll of a green and pleasant land, long sunny afternoons, the sound of leather on willow, and “old maids hiking to holy communion through the morning mist” to quote George Orwell.

Deep England is also exclusively white and rigidly class-structured, with everyone contently knowing “their place”, but those who are swayed by the myth certainly never picture themselves as farm labourers doing back-breaking manual work for a pittance as most people would have been doing at the time.

The myth is deeply embedded in English political discourse, probably too deeply to ever be eradicated, but myths are malleable things that can be changed over time, and I think the myth of Deep England is ripe for rapid evolution.

Dee Dee: How do you think myth & folklore can inform our ideas about the land and our place within it?

Paul: I mentioned earlier that myth and folklore are older, deeper stories about the land and our place in it. They allow us to see how our ideas about the land have changed over time.

One of the interesting things in folklore is the myth of ownership of the land and of course this links into how the far-right tries to manipulate folklore. However, in folklore you see that there is no real ownership, just people — usually a mix of different peoples —who were here at one particular time, calling it home.

You can read the myths, legends and history and cheer on the Celtic Boudicca fighting against the nasty invading Romans, then immediately empathise with the Romano-British King Arthur fighting against the nasty invading Saxons. A few minutes later you support the Saxon folklore figure of Robin Hood or the historical Saxon of Hereward the Wake fighting against the nasty invading Normans. There were probably once even earlier myths about some great Bronze Age British hero fighting the nasty invading Celts and others before that.

The stories are the same time and time again. We can see from them, when we look at them together, that there is no magical connection of any one people or race to the land we now call England. Nearly everyone who lives here feels connected to the land simply when they make it their home.

Dee Dee: Can you give us an example of how your depictions of the figures show how folklore and myth relate to the current climate of socio-political upheaval?

Paul: The England’s Dark Dreaming series was not intended as a series of political cartoons or sloganeering, but rather as something that I hope has weaved several themes into a more complex whole. The political is inseparable from the landscape, so the layers of folklore, land, and the movements of history are all visible in the drawings.

For example, one drawing shows the main male character of the series standing next to the poet Virgil. The composition is taken from one of Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy (in the ninth circle of Hell reserved for traitors) and refers to the predilection of the far-right for accusing anyone who disagrees with them of being traitors or ‘enemies of the people’. In another drawing we have the Glorification of Ignorance, draped in a tatty Union flag.

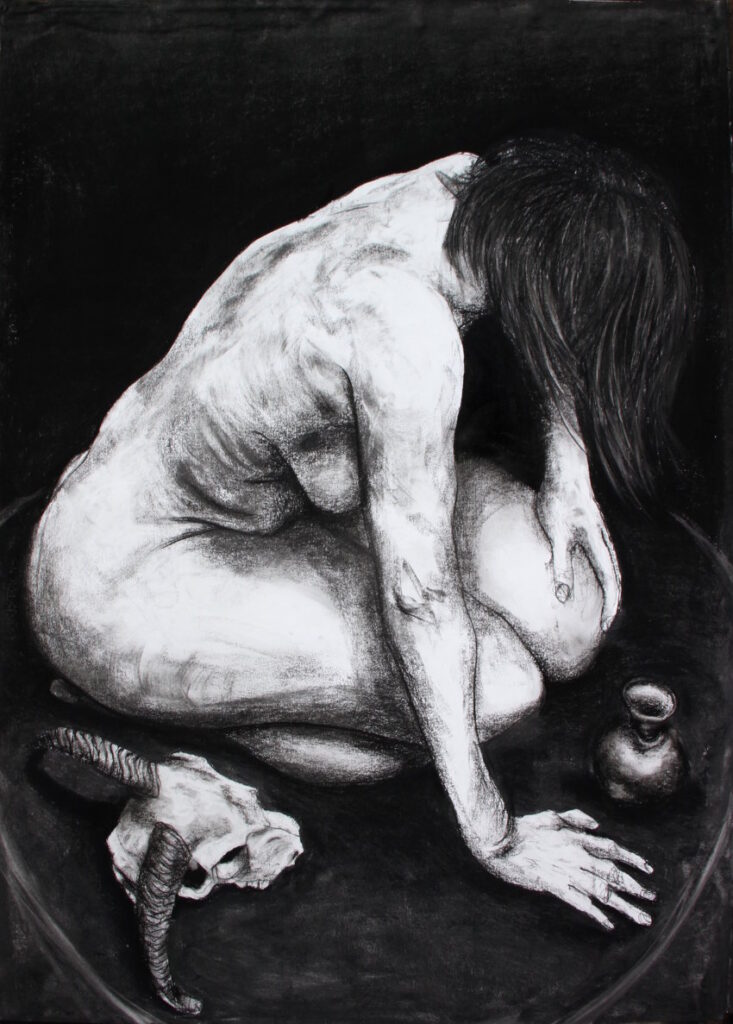

There’s also a four-part ritual (spread across four drawings) being performed by the main female character in the series, whose aim is to defeat the hatred of the far-right that has infiltrated the other main character.

Dee Dee: How did you choose which folkloric figures to include in the series, and why?

Paul: It was a fairly instinctive choice. Sometimes it came from a rough sketch or idea and other times it was my reaction to the life-model I was drawing at the time and I thought “this person would be great as…”.

There are two main characters in the series, a man and a woman, then a number of others, including, but not limited to: the Harvest Spirit, Queen Mab of Faery, Hekate, the May Queen, the Green Man and the Spirit of Albion. Like England, it’s a mixed cast.

Dee Dee: Can you give us a specific example with one of the pieces, and explain how one of the figures depicted embodies this message/ allows for the exploration of the themes?

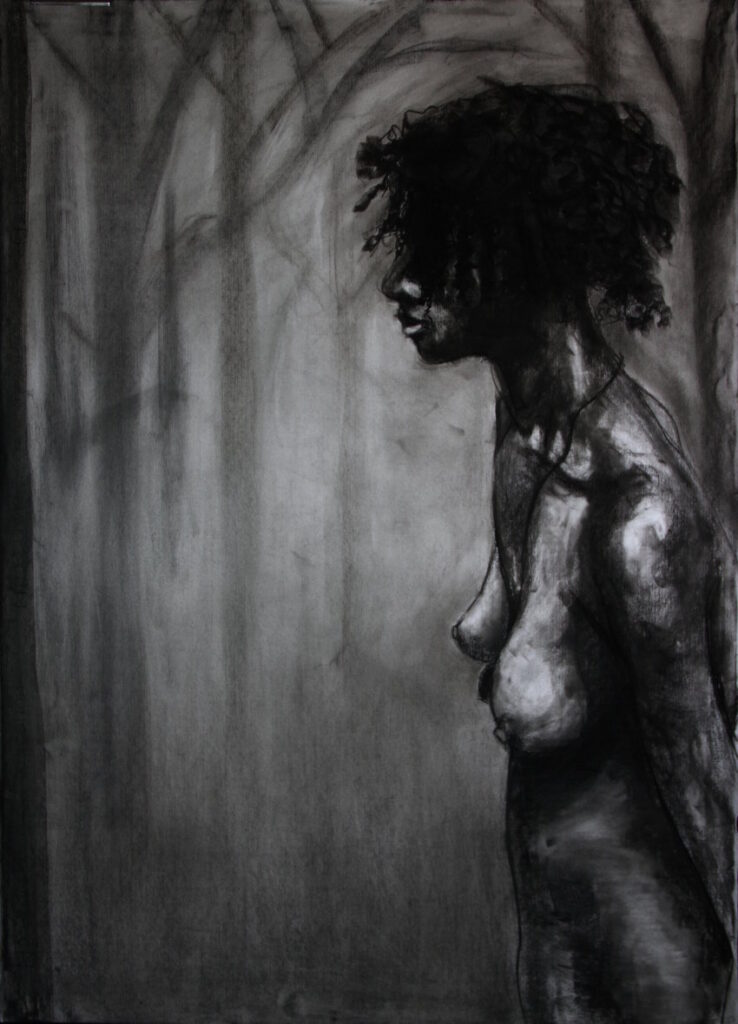

Paul: The Spirit of Albion is probably a good place to start. It’s a generic title rather than a specific folkloric/mythic figure. I made the character female and gave them an additional title of “The Memory of the Land” (a reference to one of Talis’ masks in Robert Holdstock’s novel Lavondyss). I also depicted her as a woman of colour.

I started the drawing of the Spirit of Albion (there are two drawings of them in the book) in February 2018, shortly after the results of DNA analysis of the Mesolithic “Cheddar Man” (the remains of one of the first modern Britons who lived about 10,000 years ago) showed that he had very dark brown to black skin, dark curly hair, and blue eyes.

Before the news about Cheddar Man hit the headlines I’d already arranged to work with a black life-model because I didn’t want my England’s Dark Dreaming series to reflect or support the myth of Deep England by being exclusively white — because England’s not exclusively white and there are many English people of colour. But I didn’t know what “character” they would be in the series.

Then, a few days before the drawing session, this news item was front page news everywhere and it was an obvious decision. If the current evidence shows that the first continuous inhabitants of Britain had very dark brown to black skin, then the earliest, deepest, original personification of this land would need to be a reflection of those earliest continuous inhabitants.

I’ve since found that there are two types of people on explaining the above: those who say “ah yes, that makes sense” and those who are happy to accept a Green Man with leaves erupting from his mouth, a murderous May Queen, an antlered Queen Mab and so on, but for some reason can’t accept a black-skinned Spirit of Albion. It’s a useful litmus test.

Dee Dee: If readers could take just one thing from the book, what would you like it to be?

Paul: Simply, an enjoyment of artwork. The drawings are the reason the book exists. Like folklore they can be enjoyed simply as drawings, or they can also be enjoyed with the understanding of the themes and references that are held within them.

England’s Dark Dreaming book from Paul Watson on Vimeo.

Paul’s book, England’s Dark Dreaming can be pre-ordered online now

England’s Dark Dreaming is a series of twenty-four large-scale charcoal drawings created by Paul Watson between 2016 and 2018. They draw on folkloric elements such as the May Queen and the Green Man to present a disturbing dreamscape of contemporary England in a state of political turmoil.

The book contains:

High-quality reproductions of all 24 England’s Dark Dreaming drawings.

An introductory essay about the series by the artist, as well as notes on each drawing.

A much-extended version of the artist’s article on Deep England (shorter original version can be read here).

Foreword by David Southwell, creator of Hookland.

The book can be purchased here on the Lazarus Corporation online shop. Pre-orders taken before publication will be charged at the lower price of £12.99 (exc. shipping).