Cats of musical genius and royal birth fiddle their way through some of our most beloved nursery rhymes. Known as mother goose tales in the US, some of these nursery rhymes date back to the sixteenth century. While some believe all nursery rhyme characters were based on real people, others argue they describe real historical events. What’s the truth of the matter?

Hey diddle diddle,

The cat and the fiddle,

The cow jumped over the moon;

The little dog laughed

To see such sport,

And the dish ran away with the spoon.

One of the best-known nursery rhymes, hey diddle diddle, first appeared in print in 1765: however, it’s possible this ditty is over a century older. An earlier quote which may refer to it appears in A lamentable tragedy mixed ful of pleasant mirth, conteyning the life of Cambises King of Percia, by Thomas Preston, 1569:

They be at hand Sir with stick and fidle;

They can play a new dance called hey-didle-didle.

Another possible reference exists in Alexander Montgomerie’s The Cherry and the Slae from 1597:

But since you think’t an easy thing

To mount above the moon,

Of your own fiddle take a spring

And dance when you have done.

Origin theories abound, linking this nonsense poem to everything from Hathor worship, to the naming of constellations (Taurus, Canis minor etc), or even the annual flooding of the Nile. Some have argued that it describes priests urging the working poor to work even harder and others insist that the expression ‘cat and the fiddle’ refers to Catherine of Aragon (Katherine la Fidele).

Catherine Elwas Thomas, writing in Boston around 1830, went to great lengths to prove that nursery rhyme characters were based on real people. According to her, the cat in ‘hey diddle diddle’ is none other than Queen Elizabeth I!

Iona and Peter Opie suggest this is utter nonsense and I am tempted to agree. Those fantastic interpretations are, I suspect, just that, and ‘hey diddle diddle’ is most likely an adaptation of an earlier sixteenth century work. There really is nothing new under the sun. Or over the moon in this case.

A brief comment on variants; the reader will notice that I’ve included two slightly different versions of ‘hey diddle diddle’ above. I am often asked – which is the ‘right’ or ‘true’ version of a tale. When dealing with folklore, my response would be: all of them. Especially when we’re dealing with oral tradition, as each telling is adapted to suit the audience. There is no right or wrong version. And now, back to our fiddling felines…

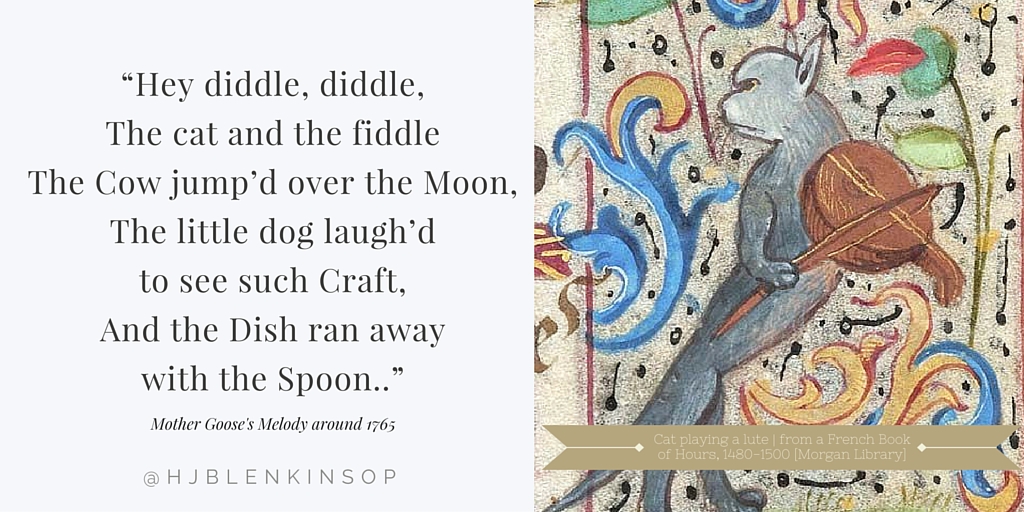

Feline musical abilities abound in nursery rhymes. Katherine Briggs comments on what she believes to be a tenuous connection with the use of cat gut, used to make fiddle strings. I share her reservations. But if you liked the fiddling cat in ‘hey diddle diddle’, how about a cat playing the bagpipes?

Here’s another variant:

Pussy-cat high, Pussy-cat low,

Pussy-cat was a fine teazer of tow.

Pussy-cat she came into the barn,

With her bag-pipes under her arm.

And then she told a tale to me,

How Mousey had married a humble bee.

Then was I ever so glad,

That Mousey had married so clever a lad.

Strange weddings between animals of different species are not uncommon in folklore, and one of the oldest recorded is A most Strange wedding of the ffrogge and the mowse, around 1580.

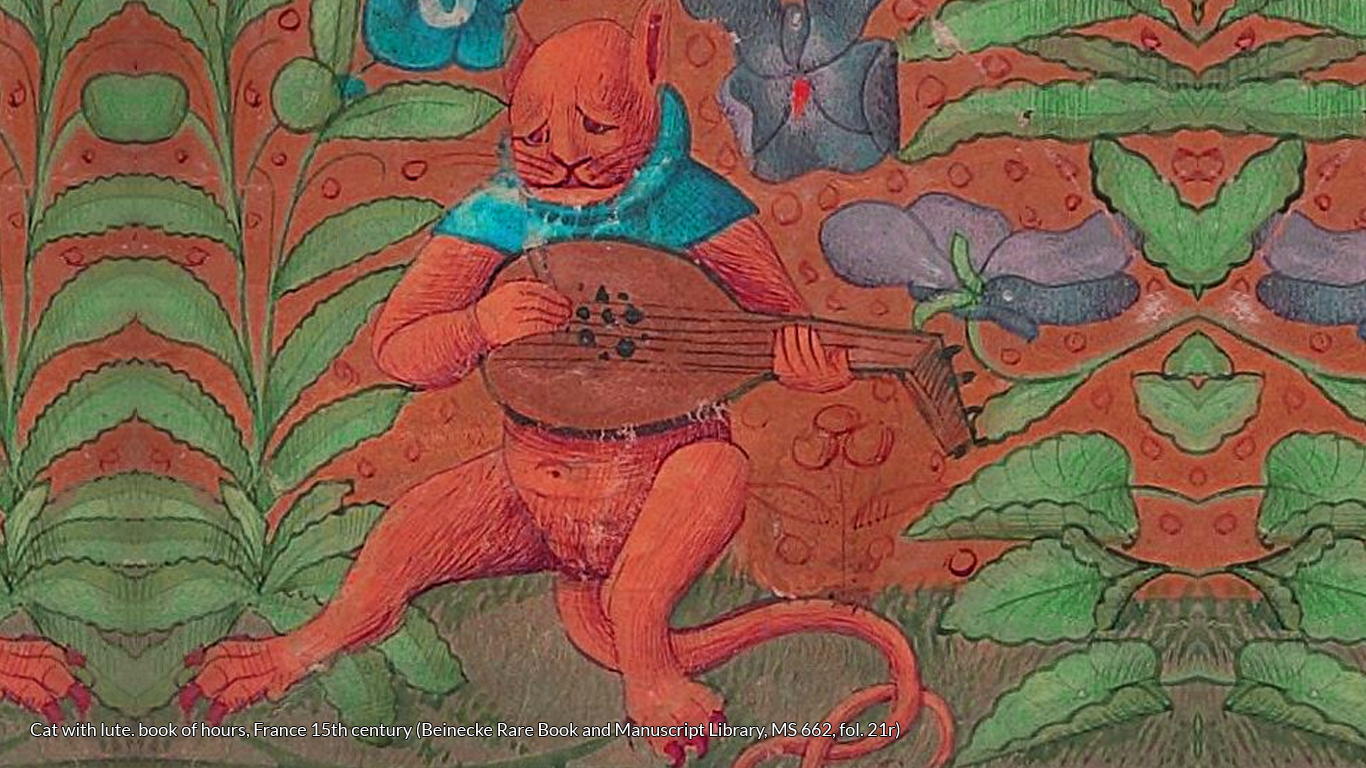

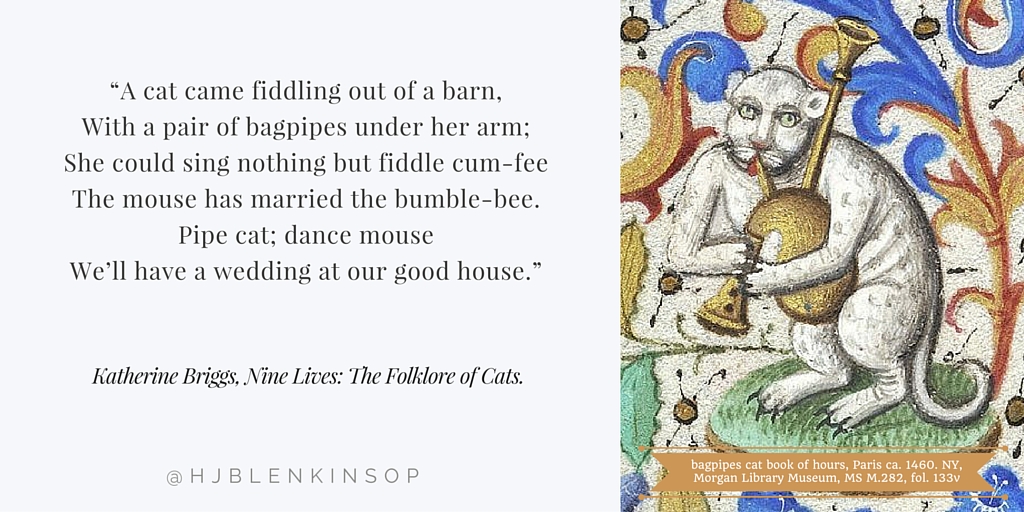

Another thought springs to mind. The images I have used to accompany our musical felines come from Books of Hours from around the fifteenth century. Is it possible that these images inspired the rhymes? I have no evidence to support this, but the images predate the verse (as far as we know) and it’s as likely as the connection between cat gut and fiddles – or ‘hey diddle diddle’ and Hathor.

No discussion of nursery rhyme cats would be complete without Ding dong dell, Pussy’s in the well.

Ding, dong, dell,

Pussy’s in the well.

Who put her in?

Little Tommy Green.

Who pulled her out?

Little Johnny Stout.

What a naughty boy was that,

To try to drown poor pussy cat,

Who never did him any harm,

But kill’d the mice in his father’s barn

Briggs suggests this might be propaganda on behalf of badly treated cats. While I wholeheartedly support cat well-being, it’s the origins of this rhyme that interest me. The Opies date the precursor of ‘ding dong dell’ to Pammelia, a collection of folk songs produced by Thomas Ravencroft in 1609. ‘Ding, dong, bell’ also appears in several Shakespearean plays including The Tempest and The Merchant of Venice.

And yet, it seems the well is deep and our rhyme dates back even earlier. In 1580, John Lant, an organist at Westchester Cathedral collected the following rhyme:

Jacke boy, ho boy news,

the cat is in the well,

let us ring now for her Knell,

ding dong ding dong Bell.

Could this little ditty be the cornerstone of one of the best loved and most often repeated nursery rhymes of all time? I think it’s entirely possible that this rhyme – and many others like it – were passed down orally from one generation to the next, varying with each telling; adding odd bits, forgetting others, until the rhyme was written down. An act which tends to ‘fix’ stories into one form or another.

Sadly, the Scottish version of ‘ding dong dell’ ends with an invitation to a funeral – the result of that rascal Tommy Green’s foul deeds. In later versions he is sometimes known as Tommy O’ Linne (perhaps a corruption of Tom a Lin, the hero of another sixteenth century song,) and later Tommy Quin.

But that’s not the version I like. Being a cat lover – and the teller in this instance – I have the power to share the version I prefer, and in this telling, the cat lives.

References:

Briggs, Katherine. Nine Lives: The Folklore of Cats, New York: Pantheon Books (1981)

Opie, Iona and Peter. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, Oxford, New York: Clarendon Press. (1951)

Thomas, Katherine Elwes. The real personages of Mother Goose , Boston: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co (1930)

Hey diddle diddle:

Text: Mother Goose’s Melody quoted in Opie, Iona and Peter (1951). The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes.Oxford, New York: Clarendon Press.

Image: Cat playing a lute | from a French Book of Hours, 1480-1500 [Morgan Library]

A cat came fiddling out of a barn:

Text: Briggs, Katherine (1981). Nine Lives: The Folklore of Cats. New York: Pantheon Books.

Image: Bagpipes cat book of hours, Paris ca. 1460. NY, Morgan Library Museum, MS M.282, fol. 133v

Ding dong dell:

Text: Briggs, Katherine (1981). Nine Lives: The Folklore of Cats. New York: Pantheon Books.

Image: HJ Blenkinsop.