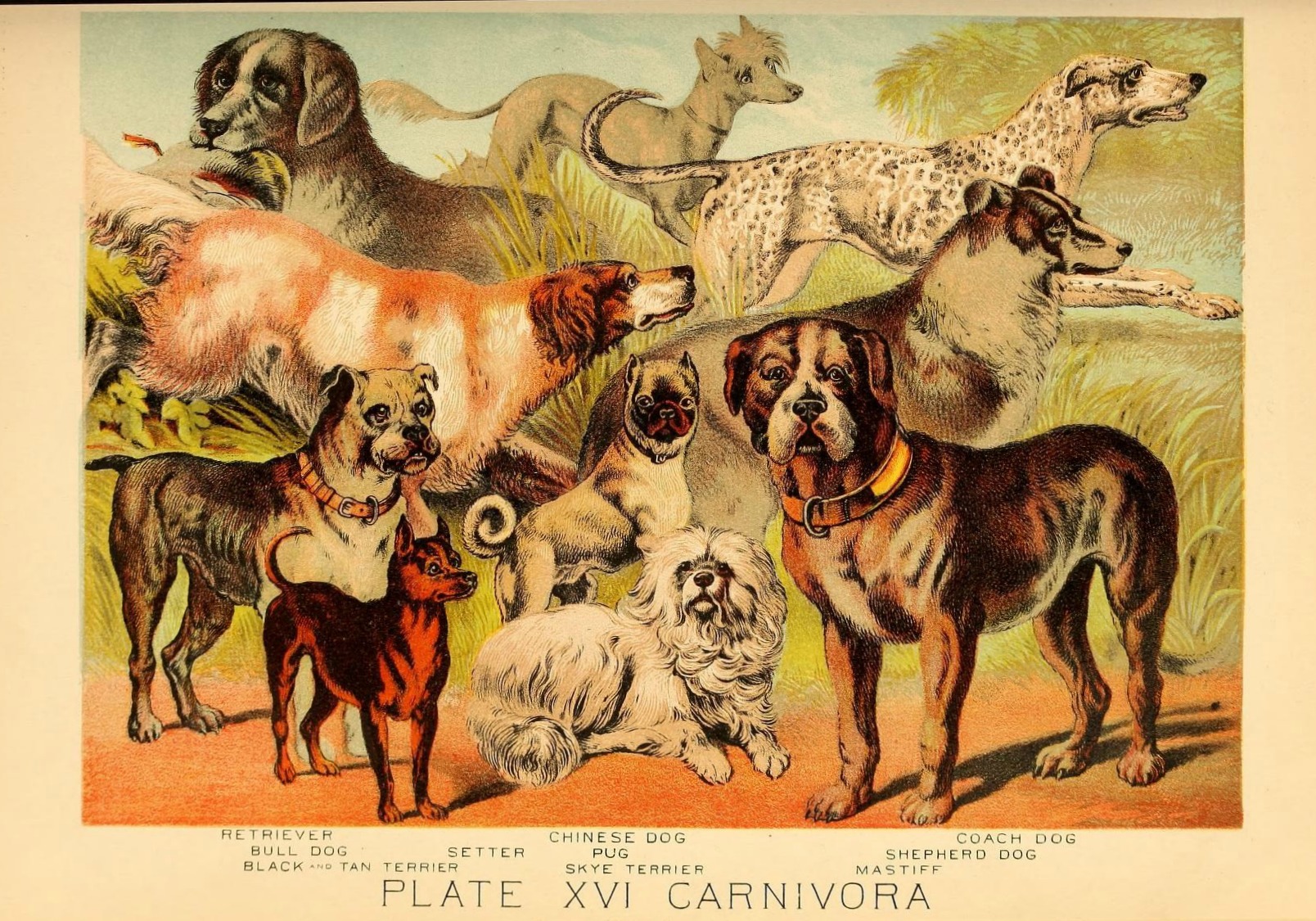

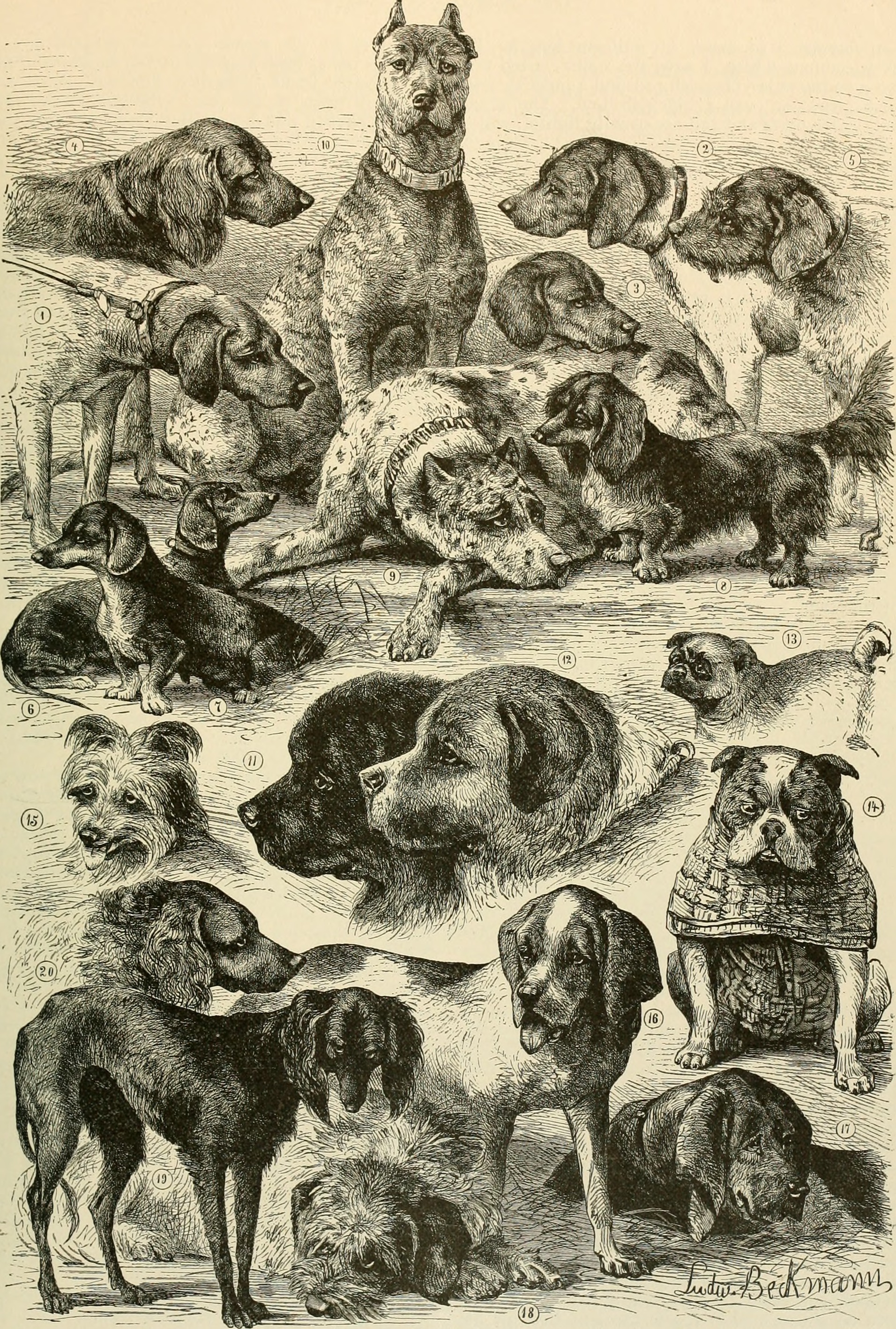

When considering dog folklore, we generally think of those stories which feature the Grimm, the Gytrash, or other sinister black dogs roaming the moors in the North of England. But there is more to canine folklore than the ominous black dogs of legend. Companion dogs, such as pugs and corgis, have their place in dog folklore as well.

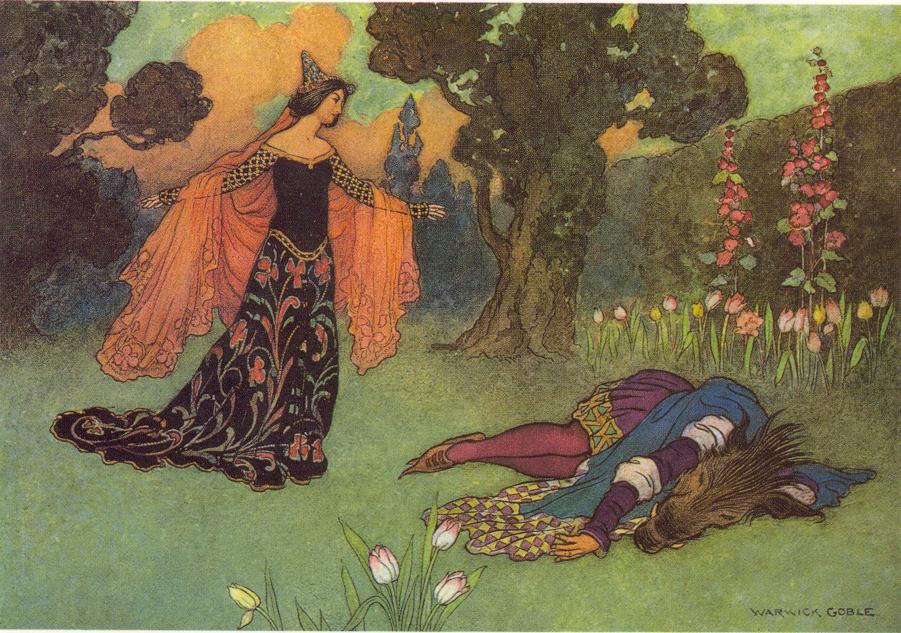

In Wales, for example, Pembroke Welsh corgis were once believed to have originated with the fairy folk. According to legend, a Welsh farmer’s children found two corgi puppies in a hollow. They were tailless with short legs, foxy faces, and gleaming golden coats with peculiar markings. Upon bringing them home, the children’s father recognized them at once for exactly what they were. In the 1997 book The Mythology of Dogs, Gerald and Loretta Hausman report that the farmer declared “surely, these are the gifts of the fairy folk.” He went on to explain to his children that corgis—also known as “fairy heelers”—were kept by the fairies in the manner of livestock and that the fairies:

“Made them work the fairy cattle

Made them pull the fairy coaches

Made them steeds for fairy riders

Made them fairy children’s playmates

Kept them hidden in the mountains

Kept them shadowed in the lee

Lest the eye of mortal man see.”

Adding credence to this story is the fact that, even today, the markings on a corgi’s back are arranged in the pattern of the magical saddles that corgis once wore when carrying their fairy riders.

Even those pet dogs unrelated to the world of the fairies were credited with having supernatural abilities. In her 2004 Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore, Patricia Monaghan reports that, in Scotland, dogs were believed to have the ability to “see ghosts of the dead, witches, or other persons only visible to people with second sight.” In addition:

“When they howled at the moon or growled at nothing in particular, it was believed that they were alerting their human keepers to the presence of supernatural or fairy powers.”

Certain breeds of dog or dogs with particular markings were thought to be especially gifted. For instance, the 2003 Encyclopaedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences states that:

“A dog with two yellow or round white spots above it eyes, can see spirits and drive the evil ones away.”

Still others believed that if you wished upon “a spotted coach dog” and then did not see that dog again, your wish would come true.

In addition to possessing the ability to see spirits or to grant wishes, dogs were also recognized for their healing abilities. In Celtic countries, it was believed that they could heal their human companions simply by being near them. This belief lingered into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and was particularly associated with pug dogs. According to Gerald and Loretta Hausman:

“Pugs were also most useful in the healing arts, skilled at pulling out fevers, relieving headaches, and drawing off serious maladies, attracting the sickness unto themselves.”

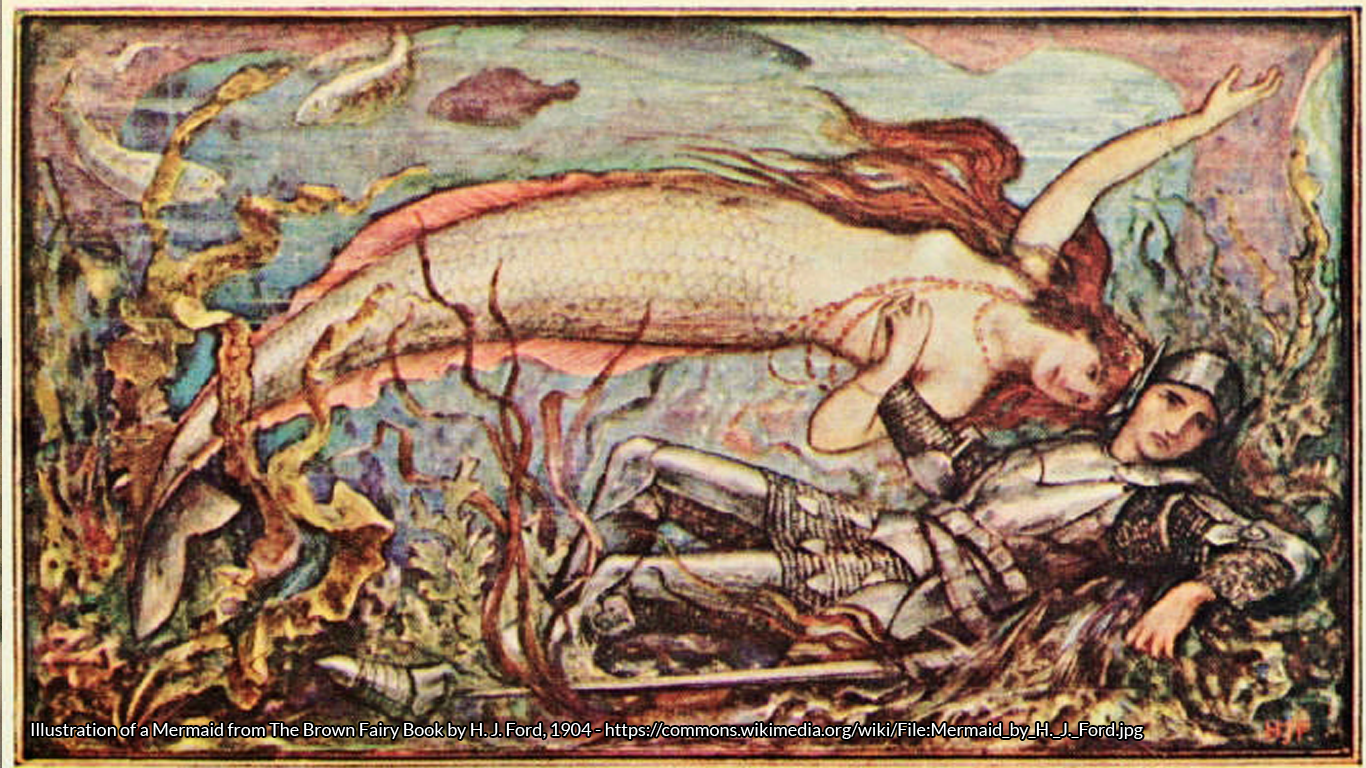

The association between dogs and healing can be traced back to Roman times, during which healing deities were often depicted as being accompanied by dogs. The Celtic healing deities, such as the healing goddess Sirona, were also depicted with their dogs. Adding to the presence of dogs in healing iconography was the fact that dogs were known to lick their own wounds until they healed. As Monaghan explains:

“This may have led to the common (if mistaken) belief in Celtic countries that dogs can heal human wounds through licking.”

Today, when one looks at companion dogs such as pugs and corgis one generally does not think of their mystical history as seers, healers, or fairy steeds. Instead, pet dogs are valued for their loyalty, intelligence, and sweet dispositions. Nevertheless, their connection to the world of superstition cannot be denied. And so, the next time you’re walking your corgi or curled up reading a book with your pug, I hope you’ll remember that—despite their adorable appearances—companion dogs have as much of a place in the realm of folklore and legend as wolves, coyotes, and the mythical Grimm.

Do check out Mimi’s new book!

Mimi’s book, The Pug Who Bit Napoleon: Animal Tales of the 18th and 19th Centuries will be released in the UK on December 11th. Find out more on her website here and pre-oder your copy now!

References & Further Reading

Encyclopaedia of Superstitions, Folklore, and the Occult Sciences, Vol. II. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2003.

Hausman, Gerald and Loretta. The Mythology of Dogs: Canine Legend. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 1997.

Ludington, Mary. The Nature of Dogs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007.

Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

Norman, Mark. Black Dog Folklore. London: Troy Books, 2016.

Sophia, Denny Sargent. The Book of Dog Magic: Spells, Charms & Tales. Llewellyn Worldwide, 2016.