Regional folklore in Madagascar spells disaster for one of the world’s most distinctive primates: the aye-aye. The aye-aye is an endangered species of nocturnal lemur found only on the island of Madagascar off the coast of eastern Africa. Through a combination of bizarre physical features and a naturally secretive lifestyle, aye-ayes have become fady to the people of Madagascar which roughly translates as “taboo.” In some regions of Madagascar, the mere sight of an aye-aye is enough to fill locals with horror and dread, oftentimes leading to the needless slaughter of these peculiar creatures. With solid education programs, the Lemur Conservation Foundation battles against the aye-aye fady to protect the lemurs of Madagascar.

“Mangatambo hita, miseho tsy tsara.”

If [the aye-aye] is seen, there will be evil.

In some regions of Madagascar, it is considered fady to eat certain lemurs, meaning local taboos can actually act as a shield to protect specific species. However, aye-ayes appear to be the only lemur associated with fady leading to their persecution. How did the aye-aye end up drawing the short straw when it comes to local folklore?

While it is challenging to pin down the exact origin of long held beliefs, researchers and scientists have speculated on the circumstances leading to the unfortunate aye-aye fady. One of the most likely culprits is the aye-aye’s striking physical appearance. They are a medium-sized, mostly black primate with large, mobile ears. They are the only primate with large, continuously growing incisors, giving them a rodent-like appearance. Most notably, aye-ayes have a long, thin middle finger used to rapidly tap along decayed wood, listening for insect larvae hiding beneath. They gnaw holes with their rodent-like teeth in order to slip their skeletal finger beneath the bark to skewer prey. According to local renditions of the fady, people are met with ill-fortune if an aye-aye points its long spindly finger at them.

The aye-aye’s eating habits may also contribute to their unpopularity amongst rural villages. Aye-ayes are notorious for raiding common Madagascan crops such as coconuts, lychees, and mangos. A certain level of distaste for the animal is cultivated simply from their position as a crop pest. But another staple of the aye-aye diet is seeds from the ramy tree (Canarium spp.). Ramy trees grow tall and undisturbed near tombs in the Samanioana region where it is fady to cut them down. Naturally, aye-ayes find the sacred burial sites and surrounding forest a peaceful place to nest and forage due to minimal human disturbance. However, the primate’s apparent preference for areas surrounding tombs may inadvertently cause villagers to physically associate aye-ayes with death and bad luck.

The degree of the fady varies greatly village by village, as does the response to an aye-aye sighting. However, one thing is clear: fear is ingrained into this fady. Several villagers even claim that aye-ayes eat people! In some northern regions of Madagascar, locals fear all sightings of an aye-aye. If the animal is seen in the forest, locals believe someone in a nearby village will consequently fall ill and possibly die. If an aye-aye is discovered in the village itself, many believe the only option is to abandon the entire village or everyone residing there will risk suffering sickness and death.

Other regions only consider the aye-aye fady when it enters a village. Locals feel uneasy about an animal intentionally displacing itself from its home in the forest to enter a village. Essentially the unnatural act of entering a “human space” from the forest is what creates the bad omen. They believe the only reason an aye-aye would display such unusual behavior is to foretell illness as the harbinger of death.

While the response to an aye-aye sighting varies wildly, all seem to agree that some action needs to take place in order to circumvent the predicted sickness or death. While a portion of residents believe total abandonment of the village is the only option, by and far, the most common response is to kill the offending aye-aye as a means to prevent human death. Villagers commonly take the carcass, or sometimes just the tail, and hang it on a pole by a crossroad with the hope that transporting the aye-aye further away from the village will help protect its residents. Some even believe that unknowing passers-by will carry away the bad luck when traveling by the carcass.

Aye-ayes are an important piece of Madagascar’s stunning biodiversity. These primates face many challenges such as habitat loss and persecution as a crop pest, but the damaging fady accelerates their already declining numbers. How do conservationists fight such widespread and pervasive beliefs? Aye-aye sightings are very rare, but the fady persists from reinforcement through storytelling. One scientist made it her mission to rewrite that story.

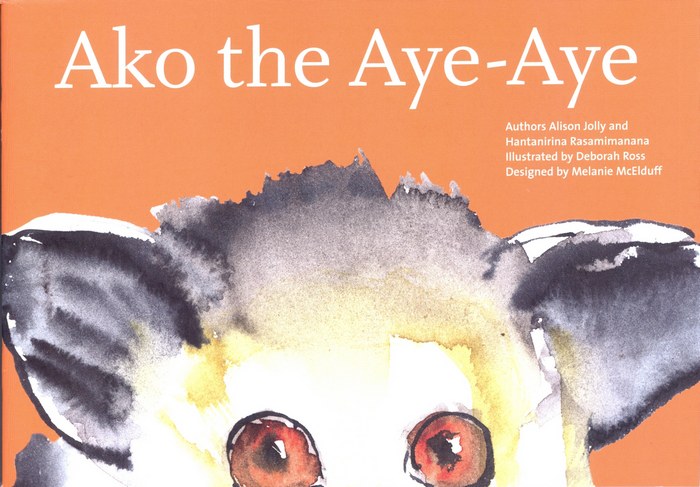

World renowned primatologist, the late Dr. Alison Jolly, authored a children’s book titled, “Ny Aiay Ako” (Ako the Aye-Aye). The book was distributed to schools and children in Madagascar to inspire a love of these bizarre creatures. The playful protagonist, an aye-aye named Ako, transforms fear into fascination. Through reading, children are inspired to protect their national oddities. The success of the first book led to a six book series, each about a different species of lemur.

Today, the Lemur Conservation Foundation (LCF) proudly continues Dr. Jolly’s work with the Ako Project. A set of 21 Ako Lemur Lesson Plans and accompanying Ako Educator’s Guide were designed to highlight the incredible biodiversity of Madagascar. Educators utilize activities featuring characters and themes from the Ako book series to teach about lemurs and the environment. LCF’s partnership with EnviroKidz makes it possible to champion lemur conservation by distributing all-inclusive Ako Conservation Education Kits to schools and zoos. Each kit includes all six of Dr. Jolly’s storybooks and the additional materials needed to inspire a love of lemurs and encourage conservation action.

The Lemur Conservation Foundation is dedicated to ensuring educators have access to the Ako Project resources worldwide. All lesson plans and supplemental materials are available to download for free on LCF’s website at http://www.lemurreserve.org/ako-project/. This project is the first step to dispelling damaging folklore by empowering children with knowledge and empathy. Global conservation education efforts like the Ako Project help to shift longstanding beliefs to give aye-ayes a fighting chance against detrimental local fady.

| Want to help save endangered aye-ayes? Follow @lemurreserve and download the Ako Project materials for free: http://www.lemurreserve.org/ako-project/ |

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

Sources and Further Reading

“Ako Conservation Education Program”, The Lemur Conservation Foundation

Mittermeier, Russell A. Lemurs of Madagascar. 3rd ed., Conservation International, 2010.

Simons, Elwyn L, and David M Meyers. “Folklore and Beliefs about the Aye aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis).” Lemur News, vol. 6, 2001, pp. 11–16.