Walter Map was a twelfth-century courtier from the Welsh Marches. His only surviving work is De Nugis Curialium (“Courtiers’ Trifles”) (c. 1181-92), a strange book in which history, religious debate and court satire are interwoven with a tangle of mythology, folklore, and eerie supernatural tales. It was perhaps these folkloric horror stories that attracted the attention of famed medievalist scholar and twentieth-century writer of ghost stories M. R. James, who edited De Nugis Curialium in 1914 and translated it from Latin into English in 1923. These editions are almost as striking for James’ lengthy footnotes on the supernatural (including a history of ‘vampires’) as they are for the tales themselves. Contained below are just a small selection of Walter Map’s macabre medieval horror stories.

Infanticide and Doppelgängers

Once, a knight and his wife celebrated the birth of their first-born child. But their joy was all too short-lived. The morning after their baby’s birth, they looked in the cradle and found it drenched in blood. Their child lay dead, his throat savagely ripped open. The knight and his wife tried to have more children, yet each time this horrific nightmare was repeated, as their second and third child were each found butchered. After the birth of their fourth child, they and their neighbours determined to keep a watch all night by the baby’s cradle.

… the unmasked and defeated she-devil leapt up and “flew out through the window with appalling shrieks and lamentations”

Just after midnight, only a visiting pilgrim was still awake when he saw the dark figure of a woman stoop over the cradle. He quickly seized her, shouting to rouse the others. A light was fetched and the company were astonished to discover that the woman was well known to them; she was a pious and noble lady from their town. Some of them ran to this lady’s house but returned in deep bewilderment with an identical lady in tow: “She was… seen to be like in all respects to the captive”. This amazed everyone but the answer slowly dawned on the pilgrim. He told the company that the woman they had captured by the cradle must be a disguised devil, who out of spite for the pious lady had taken on her likeness, hoping that she would be blamed for the child murders. Upon hearing her secret revealed, the unmasked and defeated she-devil leapt up and “flew out through the window with appalling shrieks and lamentations” (pp. 85-7).

Walking corpses, from a marginalia depiction of ‘The Three Living and the Three Dead’. The Taymouth Hours (C14th), British Library, Yates Thompson MS 13, fol. 180r.

Revenants

In Wales, a knight called William Laudun visited the Bishop of Hereford, begging him for help. William explained that his village was being decimated by a murderous, walking corpse:

“A Welshman of evil life died of late unchristianly enough in my village, and straightaway after four nights took to coming back every night to the village, and will not desist from summoning singly and by name his fellow-villagers, who upon being called at once fall sick and die within three days, so that now there are very few of them left.”

The bishop instructed William and the villagers to dig up the corpse, then “cut the neck through with a spade, and sprinkle the body and the grave well with holy water”, before reburying the undead Welshman.

… dig up the corpse, then “cut the neck through with a spade, and sprinkle the body and the grave well with holy water”, before reburying the undead Welshman.

Everything was done as the bishop commanded but it had no effect whatsoever. The corpse continued its deadly, nocturnal wanderings, until there were few left alive in the cursed village. Finally, the corpse visited William, calling him thrice by name in the dark. William decided that he would not die quietly. He jumped out of bed, drew his sword and charged at the corpse, chasing him through the night. William eventually forced the corpse back into his grave, where he “clave” its “head to the neck” with his sword. And “from that hour the ravages of that wandering pestilence ceased” (pp. 110-113).

A gleeful devil claims a dead man. Justinian, Digestum Vetus with glossa ordinaria (c. 1300-1310), BL Arundel 484, fol. 245.

Eudo and the Devil

Eudo was the son of a knight, inheriting castles, estates and wealth. However, he soon wasted it all away, ending up penniless. Following a long day of begging, Eudo sat at the edge of a wood contemplating his ragged clothes and bemoaning his lot. Suddenly, there appeared by him Olga, a devil “of wondrous stature and a visage terrible in ugliness.” The smooth-tongued devil had no trouble convincing Eudo that: “Among the living we practice laughable tricks or give real pleasure: with the dead or with the destruction of souls we have no concern.” If Eudo agreed to a pact with him, Olga even promised to send three signs before Eudo died, offering him plenty of time to repent to God and so avoid Hell.

Eudo became “gorged with blood, enriched with corpses, made merry with continual savagery, and appeased with untamed frenzy”.

Eudo agreed to follow Olga and they gathered “lawless brigands to their company”, robbing “castles and villages”, slaughtering priests and delighting in “carnage”. With the help of Olga’s demonic powers, Eudo became “gorged with blood, enriched with corpses, made merry with continual savagery, and appeased with untamed frenzy”. Once Olga started to send signs of Eudo’s approaching death, Eudo confessed his sins to a bishop and sought penance. But Eudo was soon tempted to slip back into his murderous ways. On the third occasion this happened, the by-now hardened bishop refused to grant penance to Eudo. Eudo knew this was his last chance to escape Hell and in desperation pleaded that he would do anything the bishop commanded. The disbelieving bishop dismissively told Eudo to leap into a nearby flaming witch pyre. To his astonishment, Eudo “joyfully leapt in” and “was wholly consumed to ashes” (pp. 172-185).

Henno’s wife is clearly related to the folkloric tales of Melusine, condemned to be mermaid-like half fish or serpent once a week. Couldrette, Roman de Mélusine (c. 1401-1500), BnF Français 24383, fol. 19r.

Henno-with-the-teeth

Walter Map records several tales of men who married mysterious women with supernatural powers but the most demonic of these is that of “Henno with-the-teeth” (“so called from the bigness of his teeth”). One day, Henno “found a most lovely girl in a shady wood at noonday near the brink of the shore”, weeping and accompanied by a solitary maid. When he approached them, the lady claimed to be a lost princess. The besotted Henno took her home and was delighted when she agreed to marry him. Over the following years, she gave birth to several children and all seemed well.

She then leapt out of the bath onto a new cloak which her maid had spread out for her, tore it into tiny shreds with her teeth, and returned to her human form.

But Henno’s mother began to grow uneasy. She noticed that the lady always shunned holy water and snuck out of church on Sundays to avoid receiving Holy Communion. One day, the mother made a hidden hole looking into the lady’s chamber and peeked in. She saw the lady disrobe, climb into a bath and at once transform into a monstrous dragon. She then leapt out of the bath onto a new cloak which her maid had spread out for her, tore it into tiny shreds with her teeth, and returned to her human form. The terrified mother rushed to tell Henno what she had seen and they quickly sent for the local priest. Coming on the lady and maid unawares, the priest sprinkled the two women with holy water: “With a sudden leap they dashed through the roof, and with loud shrieks left the shelter they had haunted for so long”. But her children remained and Map tells us that her “numerous progeny” are “yet living” (pp. 189-91).

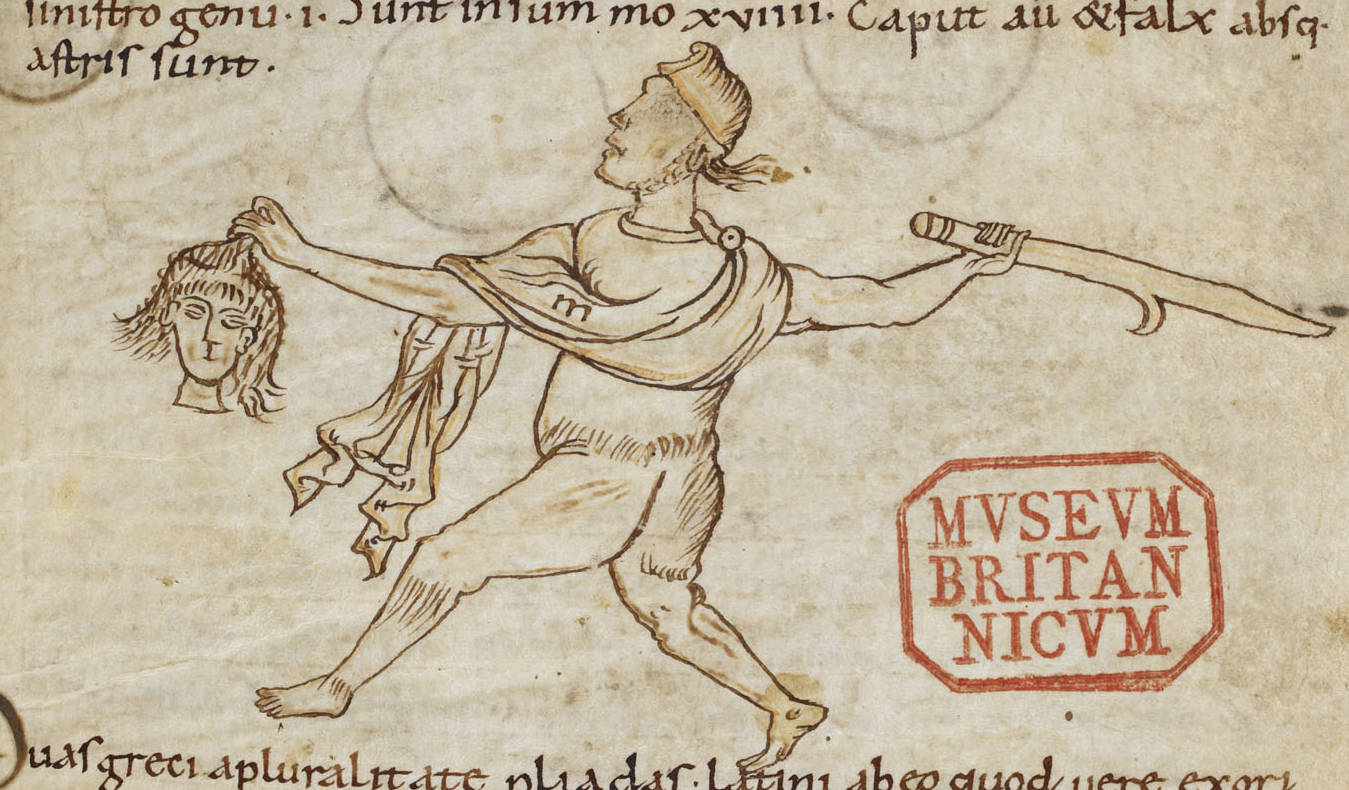

Perseus holding the head of Medusa. BL Harley MS 3595 (c. 900-1050), fol. 49r

The Haunted Shoemaker of Constantinople

This is Map’s most gruesome story. Once, a shoemaker fell hopelessly in love with a beautiful high-born lady, only to see his advances repeatedly rejected by her father. Distraught, the shoemaker left for the sea, becoming a feared pirate and determining to “gain by force her whom his low birth and lack of estates denied.” But then news reached the shoemaker that the lady had suddenly died. Grief-stricken, he immediately returned home and headed to her grave. There, he broke into his love’s tomb, embraced her “and to the dead like to the living entered her”. Having committed his necrophilic crime, he heard an eerie voice from the dead echoing around the tomb, ordering him to return to collect what the lady’s corpse would give birth to. Obeying, he returned and “received from the dead a human head.” All who set eyes upon the ghastly head instantly perished “without word or groan”.

Having committed his necrophilic crime, he heard an eerie voice from the dead echoing around the tomb, ordering him to return to collect what the lady’s corpse would give birth to.

This macabre trophy was used by the shoemaker to lay waste to all before him, claiming vast swathes of land as his own. Eventually, the former shoemaker became Emperor of Constantinople and married the previous emperor’s daughter. His new wife was terrified and disgusted by him. But she formed a plan. One night, she crept out of bed, fetched the deadly head from its box and waking her husband “thrust the head into his face”, killing him instantly. She then ordered the head to be thrown into the sea, where it sits to this day amid a vast, swirling whirlpool (pp. 201-4).

Such tales can tell us a lot about how medieval people viewed the supernatural and what they feared, from damnation and corrupting devils to resonances with infant mortality rates, plagues, class upheaval, and a fear of women “corrupting” male lineage. But why did Walter Map include these tales of supernatural horror amongst his national histories and satiric accounts of court life? It is difficult to say for certain but he perhaps offers us a clue to an ulterior, politicised purpose near the start of De Nugis Curialium:

“[As] for the rolling flames, the blackness of darkness, the stench of the rivers, the loud gnashing of the fiends’ teeth, the thin and piteous cries of the frightened ghosts, the foul trailings of vipers, serpents and all manner of creeping things, the blasphemous roarings, evil smell, mourning and horror – were I to allegorize upon all of these, it is true that correspondences are not wanting among the things of the Court… I do not… say that [the Court] is Hell; that does not follow: only it is almost as much like Hell as a horse’s shoe is like a mare’s” (p. 8).

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday

References and Further Reading

Walter Map, De Nugis Curialium, ed. and trans. M. R. James (London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, 1923).

Medieval Ghost Stories: An Anthology of Miracles, Marvels and Prodigies, ed. and trans. Andrew Joynes (Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2001).