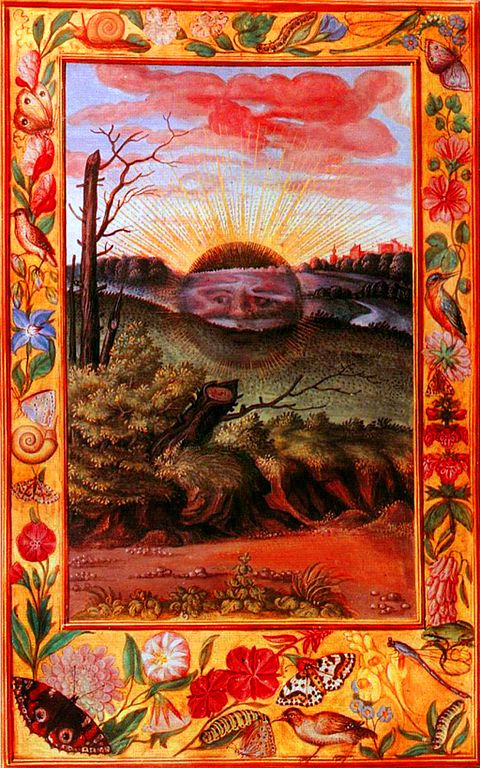

Each morning the sun rolls across the sky. In Estonia it was the hatched egg of the enchanted swallow bird, an emu’s egg bursting into flames in Australia, and a golden piece of bacon for the Nama people of South Africa. In the evening, it descends into the sea, as a bridegroom or warrior, golden rays transformed into spears or robes of light, hissing with heat as the waters close over it, before swimming back to the east. Sometimes in gloom-shrouded nights, we may imagine it will never return and we will be plunged into unyielding darkness, but still it rises and always will, at least for the next five billion years or so! The sun is stability, cosmic order, so let us trace it through the calendar year, just as Greek nymph Clytie traced Apollo’s movements until she was doomed to follow the sun forever as a sunflower. We will pause longer like the sun at solstice to shine a light on some Midsummer sun lore and customs in Britain and Ireland. Midsummer is only three days after summer solstice which falls on or about June 21st in the Northern hemisphere. These days have often been equated, traditions and customs overlap or in many sources are attributed to both.

On July 27th the Dog Days begin as the sun begins to bite with the rising of Sirius the Dog Star. Ancient Greeks and Romans thought it a distant sun that rose with our sun adding its heat, making the weather unbearable. Roman astrologer Manilius said Sirius “barks forth flame and doubles the burning heat of the sun”. On 31st October, as the sun’s strength waned, the Samhain, or feast to the dying sun, was marked by the Celts as they prepared for winter. In Midwinter, at the prehistoric Newgrange in Ireland, the sun’s rays are caught momentarily in a stone bowl. Midwinter marks the death and rebirth of the new sun and the year turns…

In Christian lore, the sun is in mourning on Good Friday and will not shine until after 3pm. On Easter Sunday in England, people once arose early to witness the sun dancing and in some parts of the country this solar dance was seen as a lamb leaping for joy in honour of the risen Christ. But on June 21st it is summer solstice when the sun is at its highest point in the sky. The sun seems to pause, stand still and linger for several minutes – hence the word solstice. From sol (sun) and stitiun (to stand still). Midsummer marks the rising of the sun to its zenith, followed by a gradual waning of its power as the year turns once more. Midsummer ceremonies and customs had their origins in ancient sun worship and purification rites and were a feature of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian settlement or influence in places such as Lowland and Eastern Scotland, Orkney, Shetland and Cornwall but soon spread.

In 1795, Reverend Donald McQueen described a visit to Ireland on Midsummer’s Eve – “it was told me we should see at midnight the most singular sight in Ireland which was the lighting of Fires in honour of the Sun. Accordingly exactly at midnight the fires began to appear…I saw on a radius of thirty miles all around, the fires burning on every eminence which the country afforded.”

In Ireland, the Midsummer fires were lit at sunset after being sprinkled with holy water. In Ireland and Scotland bonfires were lit in memory of the Baal fires, a name derived from either Celtic sun god Bel (bright) or the Saxon word bael (fire). These bonfires were believed to boost the ebbing power of this life-giving, mysterious solar fire. In Irish folklore, fairies took the form of whirlwinds to try and extinguish these powerful Baal fires but throwing burning wood in their direction usually discouraged them. Children joined hands and leapt through the embers to symbolise the growth of corn and harvest abundance. Farmers drove animals through the ashes to protect them from disease. On the Isle of Man, blazing furze was carried around cattle for the same purpose. In Cornwall, the Midsummer fire was lit by “The Lady of the Flowers” who cast flowers into the flames. Cornish elders could then predict futures by reading the fire.

17th-century poet, Naogeorgus, explained at Midsummer that special straw covered wheels were set on fire, and rolled down a mountain, so that it appeared if the sun had fallen from the sky and was rolling along the horizon, and in so doing, taking away all bad luck, especially if they plunged into water at the bottom. This wheel rolling represented the beginning of the sun’s declination. This practice dated back to the 4th century, recorded as a ritual followed by the pagan community of Aquitaine, France. Similar rituals were described around 530 by a British monk in Gloucestershire. Christians then transferred the tradition to 24th June and rededicated it to St John the Baptist.

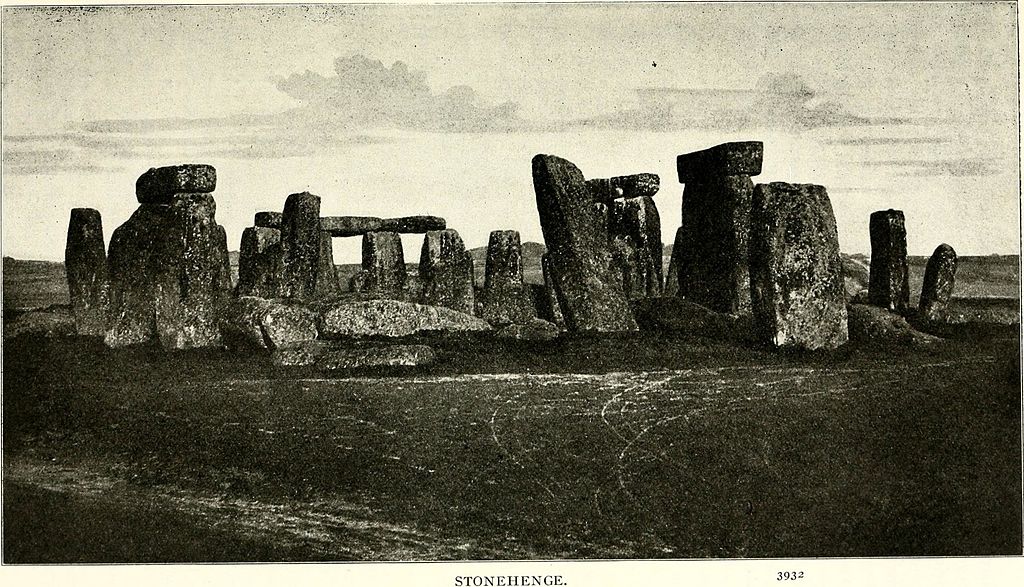

There are more than 3000 stone structures worldwide, symbolic of our obsession with the sun. Most have been constructed in line with the thresholds of sunrise and sunset but some align with the sun just once a year, usually at a solstice. Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain dates from approximately 2900BCE, and is aligned with the winter solstice sunset and to catch the Midsummer sun’s rising. A 1955 guidebook described it as “the door of the netherworld into which the sun passes at the winter solstice.” On Summer Solstice Eve, druids keep watch until sunrise to joyously greet the first golden rays. And at Parliament Hill Fields London, the Druid Orders gather for a midnight vigil to greet the sun; the moment it rises a Celtic trumpet is sounded.

The warmth of the Midsummer sun made stones dance across Britain. The Longstone on Dartmoor turned round slowly to get equal warmth on each side on that morning. At the Callanish standing stones on Lewis, if a cuckoo heralded the Midsummer sun as it fell upon “The Shining One” stone, all the stones were said to move. Those stones were once visited secretly at Midsummer when such visits were condemned by local church ministers but folk believed it wouldn’t do “to neglect the stones.” At the sacred hill of Tara in the Boyne Valley, people still gather to watch the sun rise at Midsummer.

The strength of the sun on Midsummer’s Day was believed to imbue plants with healing qualities. Women gathered herbs for healing potions for the whole year. Magical fernseeds, only seen on Midsummer’s Eve, would bring the power of invisibility. People also bathed in, and drank the healing waters of lakes that captured Midsummer sunshine, for health and good fortune. St. John’s Wort warded off evil spirits and could in legend move by itself to avoid being picked. On the Isle of Man if trodden on, on Midsummer (St John’s Day), a fairy would lift you up and lead you astray until the first rays of the next morning’s sun.

At sunset, the ancients said: “The bird of day is weary, and has fallen into the sea.”

On Midsummer Eve, according to an anonymous 1723 account, the “air is infectious with devils, spirits, ghosts and hobgoblins…” but do not worry, for when you wake, Bright Phoebus will shine on you again for all of your days.

Until then, you have the moon…

References & Further Reading

Richard Cohen, 2010, Chasing the Sun, Simon & Schuster

John Matthews, 2005, The Summer Solstice, Godsfield Press

Brian Day, 1998, A Chronicle of Folk Customs, Hamlyn

Janet & Colin Bord, 1976, The Secret Country, Paul Elek Ltd

Jennifer Cole, 2007, Ceremonies of the Seasons, DBP

Christina Hole, 1976, British Folk Customs, Book Club Associates