In December last year I gave a talk at the William Morris Gallery in London. I was nervous as hell. It is my local museum. It means a lot to me and like my local pub, I go in there often enough to be recognised. Now, I might not have picked up a lot of wisdom in my life, but one thing I learned growing up – try not to make an idiot of yourself on your own doorstep. I am not entirely sure I managed to live by that rule during my performance.

I talked about a lot of things that night. About William Morris, about political agitation and about Epping Forest – the wild shadow of London. I also talked about landscape punk, about folklore and a place called Hookland. All things that matter hugely to me.

In the talk, Epping Forest became a lens to look at landscape. It is the only royal land in England handed over to the people for our use and enjoyment. The 130 square miles of forest is the liminal blur of London, the people’s Commonwealth of the Imagination.

This is space for all of the city’s untamed thoughts. For wild stories. Narratives that demand paths that will get you lost, a gravity hill or suicide pool. In our forest, leaf fall and plant rot make ghost soil. Layers of story so deep that every walk through it scuffs up feral spirits. A natural preserve for temporal shades. We have our rights as citizens – to collect wood, to roam – and the ghosts have theirs. The Commonwealth domain shared between living and dead.

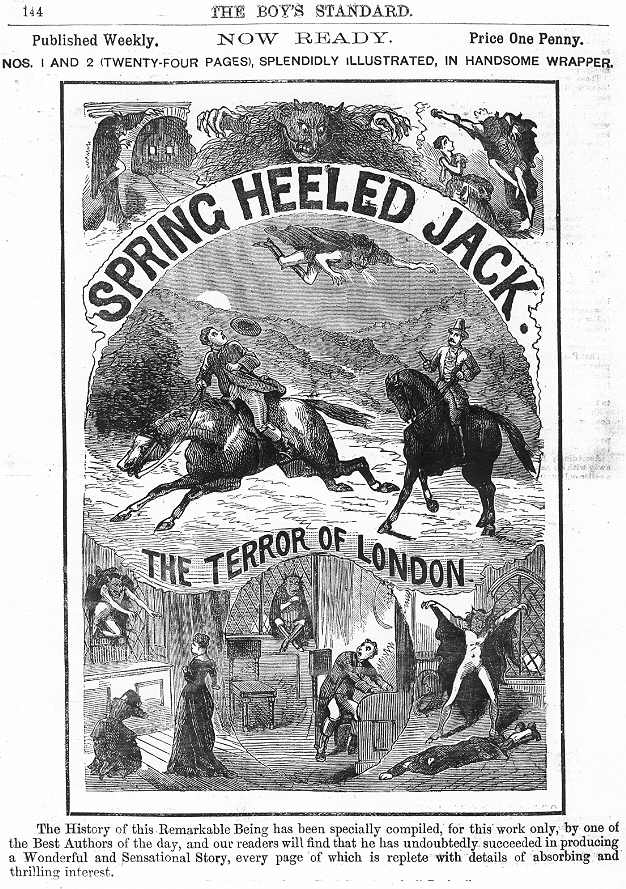

This last wild shadow of London gives shade to myth. In 1843 it was patch of Spring-heeled Jack, in 2009 the bear of Hollow Ponds. It also gives shade to more tangible monsters, acts as crime cover, becomes the city’s murder space. A lure to those with something to bury. A higher number of unidentified bodies are pulled from its mud than anywhere else in the England.

I talked about how the forest provides space in London where the imagination can still place non-human monsters in. I talked of the 18th Rabbi Falk, who in Jewish folklore buried treasure in it. The Rabbi then brought the clay from his treasure pit back to the East End of London to build a golem to protect his people from anti-Semitic paranoia. I talked about how in 2009, a new folklore sprang from the forest – the cryptid Hollow Ponds Bear. How this new monster had been adopted by the cottaging community that uses the forest. Distant centuries and the connective muscle of folklore doing what it often does, giving the persecuted a sense of protection, giving their persecutors something to be afraid of.

Through all this I was hoping that I could explain why place is so important to me. How for me it is where the imagination begins, where the stories live. I originally come from Essex, a landscape that carves a bone tattoo in you through stinging salt kisses and tides of mud. I come from an Essex landscape where as a child, before you even hit double digits, you will have walked through a whole English myth cycle of smuggler’s tunnels, Black dogs running corpse roads, Royal ghosts, witchcraft and UFOs.

Often when I speak about the spirits of a place, of temporal shades, dancing with folklore, of myth circuits, of ghost soil, some people think I am being ironic. They try to explain me to myself, tell me I am using faux occult language as part of an art vocabulary.

I am not. I never am. To me, that dance with folklore, that reactivation of the mythic circuits within us, within the land, is bloody important to me. Also, if you excluded those, it often seems to me what you end up dealing with is a way of looking at place which neglects how strange it could be.

We are in constant conversation with the land. It tells us stories as old as our fires, older than our words. Yet landscape changes, the stories stored within it decay, however that glorious marriage between the two creates folklore, creates myth. It generates legend whether in the empty wind-bullied fields of Essex or the shadow of brutal relics of the 1960s, when English cities were declared a weapon of war on those living in them. That marriage of place and story creates a constant dance in our collective memory.

And when we explore place, we get the opportunity to interact with those myth circuits running in the earth, in the stone. Get ourselves dirty wading through folklore – that dark sediment of decomposing memory, disturbed by ritual, disturbed by our being in a place.

Folklore is part of our conversation with land. A way of seeing ourselves in the narratives of place. It is our access to the psychic shrapnel of event, embedded around us. This is our line of transmission. It is echo memory, it is fault line. Folklore is narrative constantly cheating death by changing its jacket. Folklore is the liar that tells the truth of soil, of place.

Lastly I spoke about how I had wanted a way to explore that that relationship between place and folklore that wasn’t going to be dissected by theory in such a way that the mystery died on the autopsy table. Where I could connect to old, peculiar England without it being seen as ironic.

I wanted to write something fictional about the high strangeness of my childhood. How England was a weirder place back then. About how when I was growing up the TV news bulletins would carry stories about UFO sightings or ghosts in the same 15 minutes as IRA bombings. How everywhere you went, each church, alley or wood seemed to have some folklore attached to it. Everywhere seemed to be ghost soil. The whole landscape was a battery storing myth to be encountered.

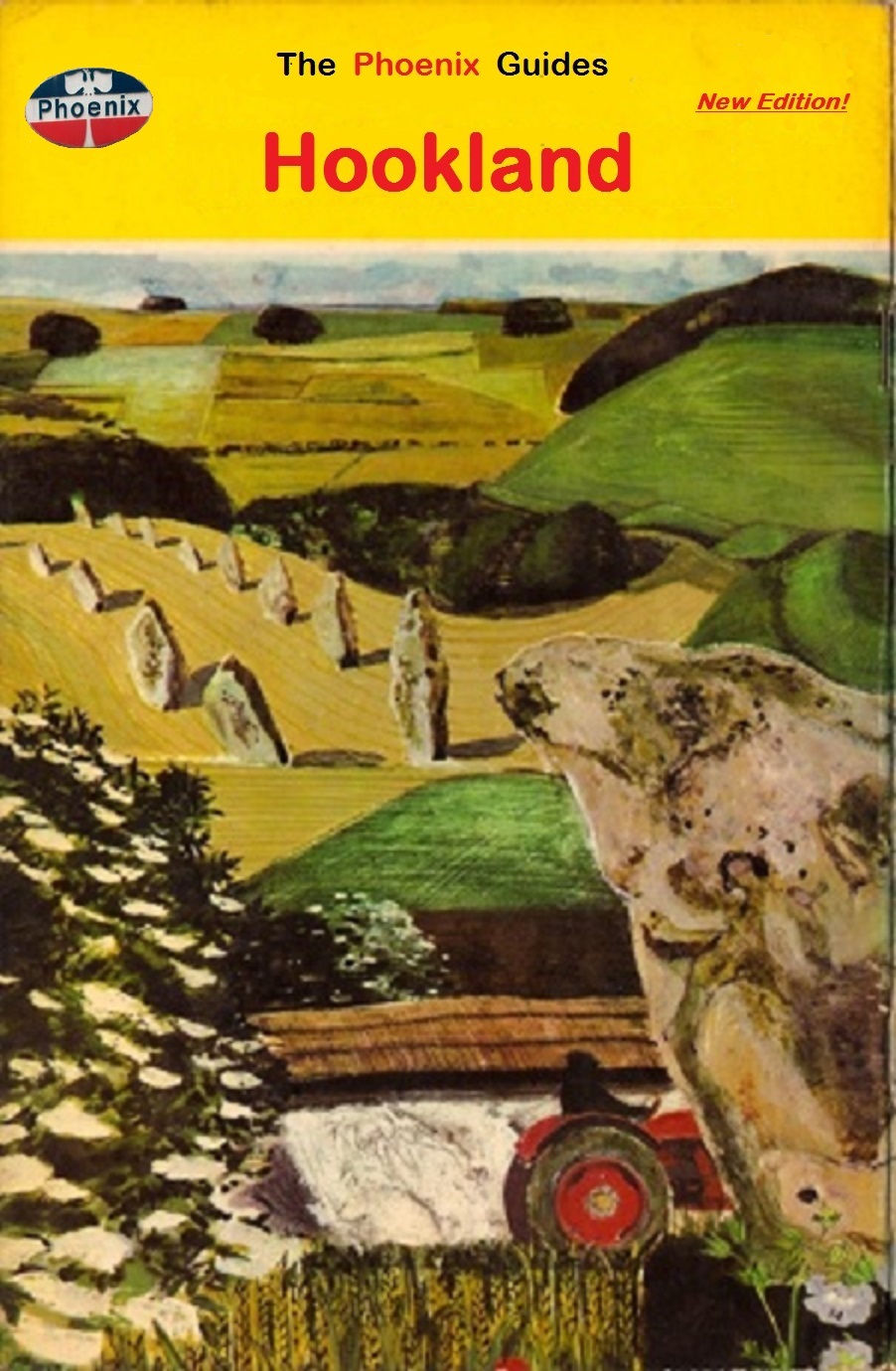

So, taking the format of a travel guide to England’s shadow-self – as given away at petrol stations when they had run out of tumblers or Smurfs – I’ve been writing the strange stories of a whole fictional county. Telling the psychogeography of place that doesn’t exist through The Phoenix Guide to Hookland. An imaginary county where nothing is made up, just remembered differently.

It is a neglected truth, but there is nothing stranger than an English seaside town. And the 1970s was peak English seaside strangeness. In Southend, the closest town to the small bit of village Essex I spend a lot of childhood in, we had drug-addicted disappearing dolphins, rows of properties left empty to haunt the front after the Kray twins were arrested, torture waxwork attractions, a thrice-cursed pier, enough explosives rotting off shore to break windows as far away as London, mysterious disappearances of people in broad daylight and military jets chasing UFOs. In Hookland I can explore those mythic memories of place with absolute freedom.

I can deal with the hills where UFO cultists who used to charge ‘aetheric prayer batteries’ atop of them. Play with those lines of pylons that so obsessed me as child as the electric ley of the land, humming stories to each other. Deal with a childhood filled with warning about ‘cunning folk curses’, those with ‘moon gardens’, with knowing that certain roads were corpse lanes, with a calendar of odd fetes and customs, unsolved murders, the odd sonic booms no-one could explain.

Hookland was always about creating this haunted space that anyone could play in. As authors we often create spaces where we want others to feel they have lived in, but then deny them permission to stay. Permission to build and explore in their own way.

It is an open, shared universe to explore those connections between place and our sometimes forgotten myth-circuits.

The England that never existed is always more powerful in our imagination than that which was there and now isn’t. Hookland is where all the secrets and mystery edited out of accepted England gets put back in. It is a reactivation of Albionic myth circuits. A love letter to the artist and author Paul Nash and a conscious act of re-enchantment; restoring high weirdness to childhood landscape.

It is a different way of approaching the strangeness held in the landscape, hopefully a bit of a landscape punk way that everybody can access without the need for theory. It is my attempt to explore folklore and its impact on our lives without academic autopsy killing the joy.

For while landscape changes and stories decay, the marriage of the two – folklore – remains the constant dance in our collective memory. As C.L. Nolan, one of the characters I created to give voice to Hookland might say: ‘Those that think folklore does not exert gravity on us, those that think it is dead, these are the people who know not themselves or the landscape they live in.’