I can clearly remember when I first became interested in gargoyles. I must warn you, however, the beginning of this tale does not involve me standing beneath the grandiose flying buttresses of Notre Dame de Paris and experiencing some epiphany about monsters and our ongoing fascination with the Other, the grotesque and horror. The truth is less sophisticated than that, and slightly more embarrassing …

I was ten or eleven and parked in front of my television in Southern California hooked on a new animated series called Gargoyles (1994-97). A child of the 80s and 90s, I often fangirled over shows that featured a team of unusual heroes who fought the forces of evil, like ThunderCats (1985-9), SilverHawks (1986) and X-Men: The Animated Series (1992-97). Gargoyles was a natural choice in the Schraner household.

The series revolved around a clan of nocturnal creatures wrongly called gargoyles—more on that later—who transform into stone at sunrise and reawaken each night with sunset. The premise of the story is pretty simple: a thousand years ago in tenth-century Scotland a clan of gargoyles were betrayed and nearly wiped out by the humans they were sworn to protect. Those who survived were cursed to sleep in their stone forms until their castle rose high above the clouds. The curse is finally broken when billionaire, and sometimes-antagonist, David Xanatos relocates the castle and its petrified monstrosities to modern-day Manhattan. Now free and allowed to resume their evening activities, it’s only a matter of time before the clan adopts the unofficial role as the city’s newest, secret night-time protectors. Without going into further detail, the series was far from rainbows and sunshine with its monstrous protagonists and antiheroes, dark undertones and tendency for melodrama.

Looking back, the series was an early, watered-down introduction to the Gothic and horror, but over twenty years later I still find myself gazing up at these fantastical stone beasts perched high above me on towering skyscrapers in Manhattan, cathedrals and churches, universities, town halls and stately homes throughout the United States and Western Europe.

Who knew decorative waterspouts could be so fascinating? Yes, those snarling stone creatures who devour countless pedestrians with their terrifying gazes are actually glorified (although some might argue ghastly) drains.

The myth and legacy surrounding gargoyles, those ‘Nightmares in the Sky’ as the king of horror, Stephen King, affectionately calls them, is colourful and varied in art history and religious studies (4). There are many interpretations regarding their symbolic role in society, but their practical function as decorative gutters in architectural design is indisputable. Art historian, Janetta Rebold Benton, maintains in her monograph, Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings (1997), the concept of fancy drainage wasn’t entirely innovative when ‘[t]rue gargoyles’ appeared at the start of the twelfth century and grew in popularity during the Gothic period (11). Crafted to prevent masonry walls from eroding, unwanted rainwater is redirected from the roof of towering structures like cathedrals and university buildings through a trough carved into the back of the carved monster. The water is then thrown clear of the structure’s wall through its snarling, gaping mouth onto the street, and its pedestrians, below.

In Europe there are various terms to describe these ‘architectural appendages’, for example, the Italian grónda sporgente describes its technical function as a ‘protruding gutter’ whereas the German Wasserspeier translates as ‘water spitter.’ My personal favourite, though, is the Dutch waterspuwer which means ‘water vomiter’, but it is the French gargouille, meaning ‘gullet’ or ‘throat’, which is the etymological source of the English word, gargoyle (8). The term has been diluted over the years and today gargoyle is often wrongly used as a generalisation for all monstrous sculptures, caricatures and fantastical creatures which appear on the exteriors of buildings. While many of these statues usually do share similar supernatural and animalistic features to gargoyles, they serve no real purpose beyond the decorative and are actually grotesques or chimeras. If we’re going to get technical, my beloved animated gargoyles fall into this latter classification of stone beasts, although I can sympathise with the producers’ decision to call the series Gargoyles instead of Grotesques.

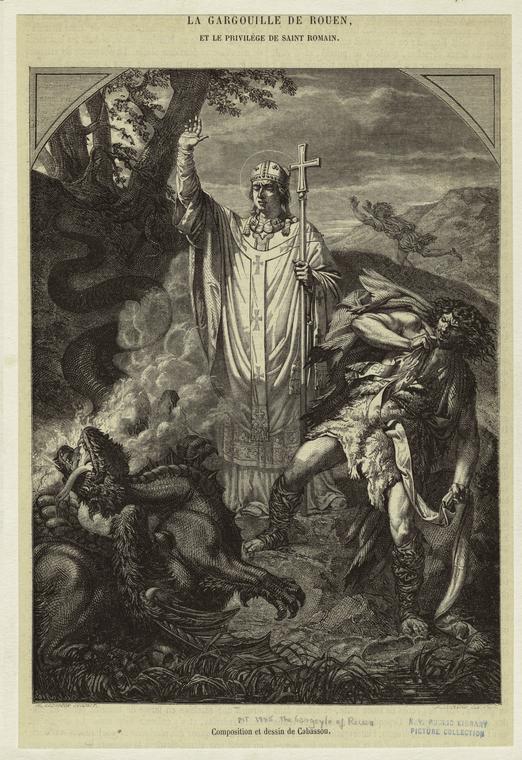

Besides the etymological origin of the term, what’s fascinating about the appearance of these petrified monsters atop cathedrals and churches during the Gothic period is that these ornamental gutters were given deeply symbolic and spiritual significance. Benton discusses the mythical origin of the gargoyle’s name in her monograph. According to legend, a dragon known as La Gargouille resided in a cave near the River Seine in France. It was ‘described as having a long reptilian neck, a slender stout and jaws, heavy brows and membranous wings’ (11). It was a nasty beastie who was notorious for swallowing ships, breathing fire and spouting—or vomiting—so much water from its mouth it caused flooding in the area. The townspeople of nearby Rouen tried to appease La Gargouille by offering a victim every year and, for once, we’re given a reprieve from the usual tale involving the sacrifice of a virgin maiden. Instead, they presented criminals to La Gargouille, giving an altogether new meaning to the concept of capital punishment, but this did not placate the greedy beast.

Sometime around the year 600 a priest named Romanus arrived in Rouen and promised to deal with La Gargouille if the residents agreed to build a church in town and join his congregation. When they complied, he set off ‘with the annual convict and the items needed for an exorcism (bell, book, candle, and cross)’ (12). Legend states Romanus subdued the dragon with the sign of the cross and got his craft on by restraining the dragon with a leash made from his own robe before leading him back to town. Like all evil creatures, the dragon was burned at the stake and everything save for the head and neck, which could withstand the heat of the flames because, well, it’s a dragon, turned to ash. La Gargouille’s remnants were then mounted on the town wall and history was made when it became the model for stone gargoyles in the centuries to come (12).

Darlene Trew Crist also mentions this French tale in her monograph, American Gargoyles: Spirits in Stone (2001), but she explores a second legend about the origin of the gargoyle in Celtic history. The Celts were distinguished hunters and believed the heads of their prey were infused with magical abilities which ‘attract[ed] luck and repell[ed] evil’ (16). After the kill, the Celts supposedly harnessed this power by mounting the prey’s decapitated head on sticks and positioning the stakes in a circle around their homes. This practice eventually evolved and expanded to hanging the heads like trophies directly on the exteriors of buildings in their villages (16).

Interestingly, the first legend is steeped in the teachings of the Catholic church—a saint overpowering an evil monster is nothing we haven’t encountered before—whereas the second originates from pre-Christian pagan beliefs. Crist argues early Christians used the figure of the gargoyle to attract pagans to worship, and Benton does acknowledge the possibility that these stone monstrosities were ‘survivals’ of paganism which the Church incorporated into their ‘decoration for superstitious reasons’ and improved attendance numbers (23). Once absorbed, it was only a matter of time before the gargoyle was fully seized by the Church and adopted the role of protective ward. Folklorist Katherine Briggs maintains the gargoyle, along with church bells and the weathercock, has long been believed to be one of three known ‘defences against the Devil’ (20). This interpretation of the gargoyle as a ‘sort of sacred scarecrow’ subsequently inspired artists and authors to create truly grotesque creations to keep such evil away from holy places and protect the Church’s loyal parishioners (Benton 24). Some gargoyles, however, like the ones sitting atop Notre Dame de Paris take their roles as protector a step further than most and apparently keep an eye out for people drowning in the Seine (39).

But the line between good and evil is a fine one indeed and not everyone viewed these stone carvings, which feature an array of animals, humans and fantastical beasts, as grotesque guardian angels. Some argued these monstrous creations were merely stone demons—representations of ‘evil forces’ like sin and temptation—which skulked outside the safe confines of church and waited patiently for its next victim (24). Another interpretation along this vein suggests gargoyles were the embodiments of mortal ‘souls condemned for their sins’ and, while they were saved from damnation in hell, the cost of their transgressions is their eternal petrification atop a church they are no longer allowed to enter (25).

Regardless of their symbolic meaning, we need to remember that gargoyles were created during a period of mass illiteracy in Western Europe. They were both a form of entertainment and responsible for shaping the narrative of public behaviour. Towns and cities were, and still are, overrun with these nightmarish creations, forcing its inhabitants—forcing us—to question the relationship between sin and salvation, good and evil, reality and fantasy, fact and superstition, the visible and invisible each time we drop our head back and gaze up at them in the sky.

It’s no secret that our fascination with all things monstrous, the macabre and horror has not dissipated in the slightest throughout the ages—it’s part of the human condition and is precisely the reason why gargoyles have endured in popular culture today. Sculptors haven’t abandoned these beasts and new carvings still appear on modern buildings around the world. Moreover, gargoyles continue to make appearances in films and television—Stephen King speaks candidly in his essay for Nightmares in the Sky (1988) about his love of the made-for-TV film, Gargoyles (1972)—and Disney has recently announced they are producing a new live-action film of the cult animated series I fell in love with as a child. But I think it is their appearance in print culture, especially in comics like Batman wherein our antihero is often seen crouching in the shadows of Gotham’s fierce gargoyles, which draws upon the enduring allure of these stone creatures.

They’re always watching us, but the question still remains: Why?

References and Further Reading:

Benton, Janetta Rebold. Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings. New York, N.Y.: Abbeville Press, 1997. Print.

Briggs, Katherine. An Encyclopedia of Fairies: Hobgoblins, Brownies, Bogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. New York, N.Y.: Pantheon Books. 1976. Print

Crist, Darlene Trew. American Gargoyles: Spirits in Stone. New York, N.Y.: Clarkson Potter 2001. Print.

King, Stephen. Nightmares in the Sky: Gargoyles and Grotesques. With photographs by f-stop Fitzgerald. New York, N.Y.: Viking Studio Books.