In Tudor and Stuart England, angels were understood to be intermediaries between God and women and men, and they also carried out a range of other functions on Earth. They delivered messages, protected the godly, carried souls to heaven after death, punished sinners, and were responsible for carrying out God’s will on Earth.

In sixteenth and seventeenth-century England, people believed in angels. Why wouldn’t they? There was plenty of evidence for them in the Bible: their appearance, their names, their responsibilities, and their interventions in earthly life. Scriptural angels carried messages to humankind providing comfort and instruction, they dispensed divine justice, and they joined with humanity to worship and honour God. Church of England services and sermons reinforced these expectations, a message that was underpinned by images of angels that looked down from stained glass windows or from the roof of the church itself.

Yet whilst the ‘official’ Church position on angels was relatively clear, it is harder to find evidence of what ordinary folk thought about celestial beings. In this post I draw on a range of diaries, plays, letters, and popular cheap paperback print (particularly ballads – the early modern equivalent of the pop song), to sketch out some common expectations about angels in Tudor and Stuart England.

Protection

The most common expectation about angels was that they were the special defenders and protectors of humankind. In times of danger or distress, it was usual to react as Hamlet did when first confronted with a spirit in the form of his father. He called on ‘Angels and ministers of grace’ to defend him, or later he prayed, ‘save me, and hover o’er me with your wings’. There were also parallels in everyday life. For instance in ballads adventurous London maidens hoped for good angels to guide them, and fearful virgins and oppressed widows were defended by them. In a touching letter to his new wife, prior to their emigration to New England in 1629, the physician John Winthrop consoled her with this notion of angelic defense, saying:

My deare wife be of good courage, it shall goe well with thee and us…he who gave his onely beloved to dye for thee, will give his Angells charge over thee, therefore rayse you thy thoughts, and be merrye in the Lorde.

The archangel Raphael was particularly associated with the protection of travelers. This helps to explain why good angels were often evoked at the beginning of a journey, which could be a dangerous and uncertain undertaking at the time. People also asked for the protection of angels during times of warfare, not least because the archangel Michael was believed to be the commander-in-chief of the heavenly hosts.

The Afterlife

Not surprisingly, angels also had a central role to play in the afterlives that people envisaged for themselves. Many people hoped that after their deaths they would be welcomed by the angels into heaven. In ballads people looked forward to this post-mortem consolation, whilst those they left behind often commented on the assumed destinations of the departed. It was said of one man that ‘no doubt his soul to heaven is gone / Where Angels sing and never cease’.

There was also an assumption that angels were the stewards of the soul after death, carrying them to their final destination. This belief is summed up neatly by Horatio’s familiar parting words to Hamlet: ‘Goodnight sweet prince, And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest!’ In a less serious context, Samuel Pepys recorded a ‘good story’ told by a dinner companion, Mr. Newman. Newman was a New England minister who preached a funeral sermon foretelling his own death. Pepys related that at the sermon’s conclusion, Newman ‘did at last bid the angels do their office, and died’.

The association between angels and the afterlife gains its most resonant expression when Balthasar informs Romeo of Juliet’s (supposed) death. Balthasar says: ‘Her body sleeps in Capel’s monument / And her immortal part with angels lives’. The consoling message also comes across very strongly in those ballads relating to the deaths of pious children. After reassuring her mother that her coming death will be a release from ‘sorrow, trouble, care and strife’, a ‘pious daughter’ saw angels all around her deathbed, ‘sweet Messengers that wait for me, Who on their Wings will me convey, Where peace and joys will ner decay’.

Plague Angels

Angels were not only considered to be instruments of God’s mercy however, they also functioned as executors of his justice. In particular, it was thought that God’s ‘destroying angel’ was responsible for inflicting plague on sinful people. In a 1615 sermon by Thomas Hastler, he described how the angel was ‘darting the rightaiming arrows of the Lord’s wrath at euery mans doore’. The anonymous author of a 1626 pamphlet titled Londons Lamentations and teares warned those that tried to flee the consequences of their sin that ‘Angels haue Wings, and can flee faster than any of your Coaches can hurrie, or your Geldings can gallop’. In 1666 a parliamentary army officer gave thanks for the ceasing of the epidemic in London, writing that ‘God was amongst us, and did hear the prayers of the destitute for that city, and did cause the destroying angel to put up his sword’.

On the other hand, angels also had a close association with healing and the medical profession. The traditional understanding of the archangel Raphael’s name was ‘medicine of God’, and one theologian described him as ‘the Lordes phisicke or phisition’. Again, this was a belief that had scriptural origins – the Book of Tobit provided examples of Raphael’s medicinal miracles. The ability was also derived from the Gospel of John, when an angel descended from heaven to stir the waters of the Pool of Bethesda, which were then endowed with healing properties.

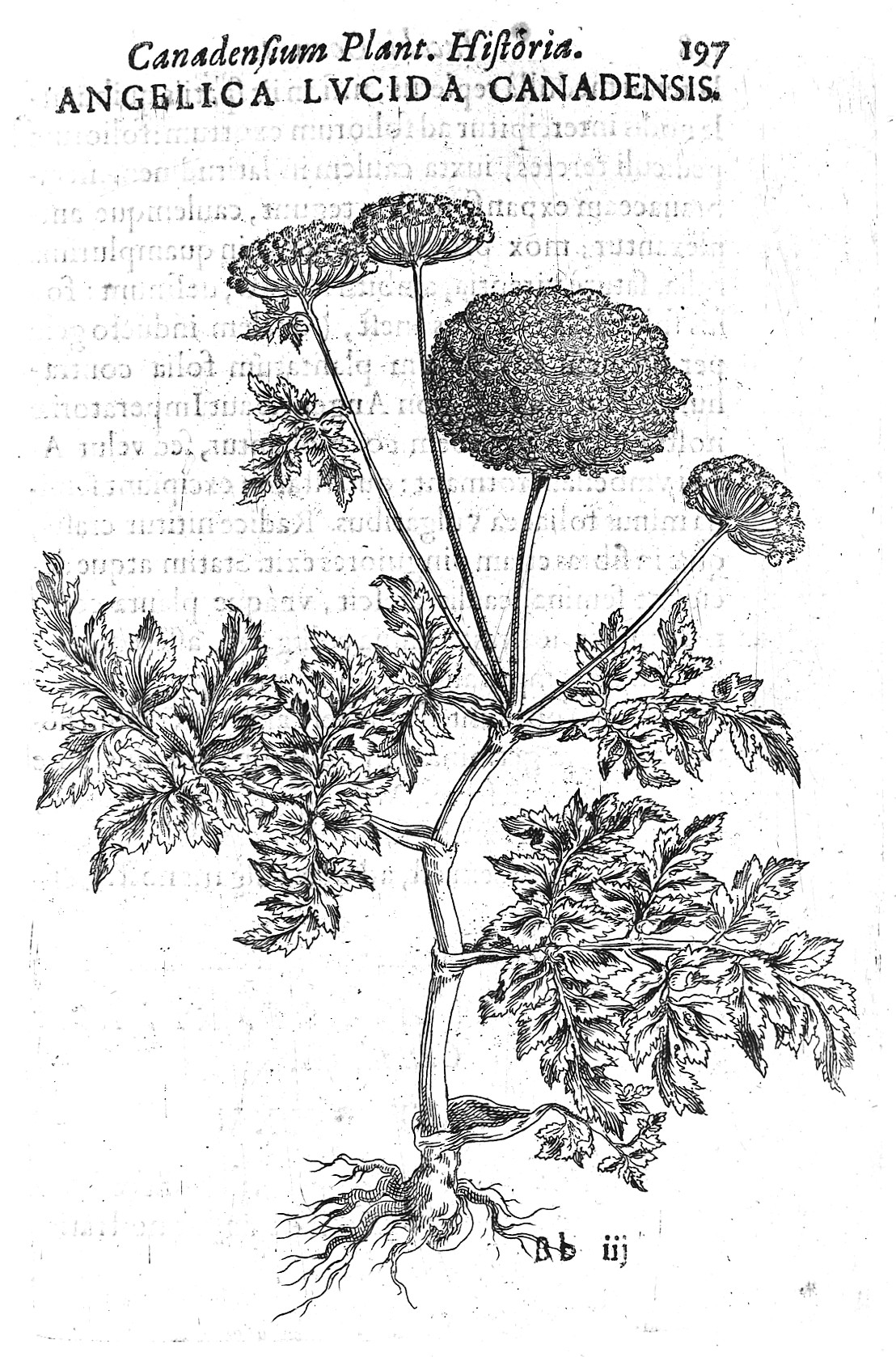

Perceptions of a connection between angels, the plague, and healing may also have been fueled by one of the common ingredients of the plague remedies that were very widely employed at the time. A herb known as ‘angelica’ often formed the basis of the cordials, compounds and perfumes that were recommended as treatment for the plague. As its name suggests, angelica was linked in the popular mind with angelic patronage. According to one legend, its plague-curing properties were revealed by an angel in a dream, whilst another suggested that it would bloom only on Saint Michael the Archangel’s feast day. In his treatise on the pestilence, Thomas Brasbridge provided a tentative endorsement of such views, saying that:

We may call it Hearbe Angel, or, the Angelical or Angelike Hearbe. Vppon what occasion this excellent name was first giuen vnto it, I know not: vnlesse it were for the excellent virtues thereof, or for that God made it known to man by the ministerie of an Angel.

Angelica was recommended and employed as an effective medicine against the plague by clergymen, regular physicians, and government officials alike. Orders issued periodically by the king and Privy Council during outbreaks of plague advised that ‘when one must come into the place where infectious persons are, it is good to smell the roote of angelica…and to chew in the mouth’. The herb also appeared in many of the ‘easie medicines of small charge’ that appeared in the directions set down for the prevention and cure of the plague by the College of Physicians in 1636.

I’ve only scratched the surface of the beliefs that clustered around celestial beings in Tudor and Stuart England here, but hopefully I have conveyed a sense of the range of expectations associated with them. These expectations included their more intimidating, as well as their friendlier aspects, and demonstrate the ‘patchwork’ of traditional and reformed beliefs that connected and overlapped in the pre-modern mind.

Recommended Books from #FolkloreThursday

References & Further Reading

Laura Sangha, Angels and Belief in England, 1480-1700 (Pickering & Chatto, 2012).

Anon, The Dying Mans good / Counsel to his Children and Friends. / Being a fit pattern for Old and Young, Rich and Poor, Bond and Free to take example by (London, [1680-1695]) R234259.

Anon, The Sorrowful Mother, / OR, / The Pious Daughters Last Farewel. / She patiently did run her Race, / believ’d the Word of Truth; / And Death did willingly embrace, / tho’ in her blooming Youth (London, [1685-1688]), R227382.

Anon, Lachrymae Loninenses: or, Londons lamentations and tears for Gods heavie visitation of the plague of pestilence (London, 1626).

The Diary of Samuel Pepys: with an introduction and notes, ed. G. G. Smith (London, 1906).

Thomas Brasbridge, The poore mans Ieuuel (London, 1578).

Thomas Hastler, An antidote against the plague (London, 1615).

Henry Holland, Spirituall Preseruatives against the pestilence (London, 1603).

Life and Letters of John Winthrop: Governor of the Massachusetts-Bay Company at their Emigration to New England, 1630, ed. R. C. Winthrop (Boston, 1864).

Orders, thought meete by his Maiestie, and his Priuie Counsell, to be executed throughout the counties of this realme (London, 1603).

Original memoirs, written during the great Civil War; being the life of Sir Henry Slingsby, and memoirs of Capt. Hodgson. With notes, &c (Edinburgh, 1806).