Ask anyone for the names of the great fairy tale tellers, and most people will answer Charles Perrault, the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. A few may summon up the names Andrew Lang, Oscar Wilde or George Macdonald. But hardly anyone will mention Mary de Morgan, Pre-Raphaelite, suffragette, and one of England’s first feminist fairy tale writers, even though her literary fairy tales were as beautiful, strange and eerie as any told by the famous men above.

‘Help me, sweet Love!’ she cried, and then began to weep.

‘Poor Queen Blanchelys!’ said Love. ‘Your rose-tree is dead then.’

‘My tree is dead,’ sobbed Queen Blanchelys, ‘and the King loves me no more. Ah, tell me who has killed my tree?’

‘Your cousin Zaire has killed it,’ said Love. ‘She asked Envy to help her, and Envy has given her a viper, which she laid at the tree’s roots, and it has spat its deadly venom on to the red heart (of the rose) … and killed it.’

‘Tell me, then, how to make it live again,’ gasped the Queen.

‘There is only one thing in the world that can do that!’ said Love.

‘And what is that?’ asked the Queen.

The blood from your own heart,’ said Love.

— ‘Seeds of Love’, On A Pincushion & Other Fairy Tales (1877), Mary de Morgan

Mary de Morgan was born in London in February 1850, a month of wild storms in which windows were broken by hail, slates were torn off roofs, chimneys were blown down, and ships were wrecked upon the shore. She was the youngest daughter of the brilliant mathematician Augustus de Morgan and his wife Sophia, who was tutor to Ada Lovelace, the daughter of Lord Byron and an accomplished mathematician herself.

When Mary was three years old, her sister Alice died from measles at the age of 15. This great sorrow drew her mother into spiritualism, and she began to hold séances in her home and to attend lectures and demonstrations by mediums. At the age of six, Mary began to dream about Alice, seeing her playing in a garden attended by doves and haloed with gold. Her mother Sophia began to record Mary’s dreams and other psychic occurrences (including Mary’s uncanny ability to tell people’s futures from reading their palms). Sophia de Morgan’s book, From Matter to Spirit: The Result of Ten Years’ Experience in Spirit Manifestation, was published in 1862, when Mary was thirteen. It is one of the seminal work on spiritualism in Victorian times.

A year or so later, Mary and her favourite brother, William de Morgan, met William Morris and were drawn into the circle of Pre-Raphaelites. William de Morgan eagerly adopted the principles and philosophies of this group of free-thinking bohemians, and became a famous potter, designer and novelist. Mary and her brother were frequent guests at the Morris home, and were well acquainted with Edward Burne-Jones and his family, and with Christina Rossetti and her artist-brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Mary was known for her boldness and outspokenness. She once told the landscape artist Henry Holiday: ‘All artists are fools! Look at yourself and Mr. Solomon.’ Agnes Poynter, Georgiana Burne-Jones’s sister, wrote of her at the time: ‘She chattered awfully, and Louie, she is only just fifteen. I believe a judicious course of snubbing would do her good!’

Mary’s mother Sophia was an early campaigner for women’s rights, attending meetings and marches, and signing the famous petition of 1866. From the age of sixteen, Mary was active in the suffragette movement too, and was also involved with her mother in the fight against animal cruelty.

Her family were sadly riddled with consumption, and in Mary’s late teens she lost her brother George, her sister Chrissie and her father. Sophia and Mary moved in with William in his rather ramshackle artist’s lodging, and Mary began to write stories of her own. Her first publication was in 1873, a collection of stories co-authored with a female friend, Edith Helen Dixon, and entitled Six by Two: Stories of Old Schoolfellows.

In 1873, at a Christmas party at the Burne-Jones’s house in Kensington, Mary entertained the children by telling them fairy tales. Her audience included Jenny and May Morris, Philip and Margaret Burne-Jones, and their cousins, Rudyard and Alice Kipling, and Angela and Denis Mackail. The children were enchanted and kept begging her for more. Mary wrote down the stories she told them, and these were published in 1877 under the title On A Pin-Cushion, when she was just twenty-seven.

Some of the tales in this collection are just extraordinary. There’s ‘The Story of Vain Lamorna’, a pretty girl who is badly scarred in her quest for beauty and only then realises the emptiness of vanity; ‘The Seeds of Love’, a tragic tale of love gone wrong; and ‘The Toy Princess’, a subversive tale about a princess whose fairy godmother rescued her from the stifling etiquette of the royal court and replaced her with a robot-princess who only spoke a few stock polite phrases. The real princess is brought up by a fisherman and his family and learns the value of hard work and true love. I love this last story of Mary de Morgan’s in particular, and retold it for my collection of feminist fairy tales, Vasilisa the Wise & Other Tales of Brave Young Women, (illustrated by Lorena Carrington & published by Serenity Press).

Another fairy tale collection, Necklace of Princess Florimonde, was published in 1880. The stories show her strong liberal philosophies, with tales like ‘The Bread of Discontent’ illuminating the evils of poor-quality mass-produced goods, in contrast to the loving work of artisans and craftspeople.

In 1887, Mary’s brother William married another artist, Evelyn Pickering, who (under her married name, Evelyn de Morgan) became one of the most accomplished (and mystical) painters of the later Pre-Raphaelite movement. Mary had to move out and live on her own, supporting herself as a typist while she continued to write. Her tragic novel of social realism, A Choice of Chance, was published in that same year. Her friendship with William Morris continued to deepen, and she became involved with his activities with the early British socialists. She undertook social work in East End slums, attended suffragette rallies, and in 1899, joined Emmeline Pankhurst’s ‘Women’s League’.

In 1898, she was one of the few people admitted to William Morris’s bedchamber as he lay dying of tuberculosis. She helped nurse him and told him stories to keep him entertained, and helped his wife Jane and daughter May embroider the famous bed-hangings which can now be seen at Kelmscott Manor. In 1900, Mary’s last book The Wind Fairies and Other Tales was published, and five years later she went to Egypt to run a reformatory school for girls. She died in Cairo in 1907, of tuberculosis.

In 1963, Victor Gollanz published, The Necklace of Princess Fiorimonde – The Complete Fairy Stories of Mary de Morgan, with an introduction by Roger Lancelyn Green. Mary is quoted as saying: ‘I am so thankful I have only a small income – it is so delightful planning things and deciding what one can afford. It would bore me to death to be rich!’

I find the life and work of Mary de Morgan utterly fascinating. I badly wanted to tell her story in my novel, Beauty in Thorns, inspired by the lives of the Pre-Raphaelite sisterhood, but in the end her chapters ended up on the cutting-room floor. Maybe one day I will turn them into a novel!

It has been suggested that Mary de Morgan’s stories have been forgotten because she was a woman, and certainly her feminism was radical and confronting for the times in which she lived. It may also be because many of her tales ended tragically, eschewing the traditional ‘happy ever after’ denouements of classic fairy tales. Not all stories end happily, however, and there is something so powerful and sorrowful about Mary de Morgan’s struggle to change the world through her storytelling.

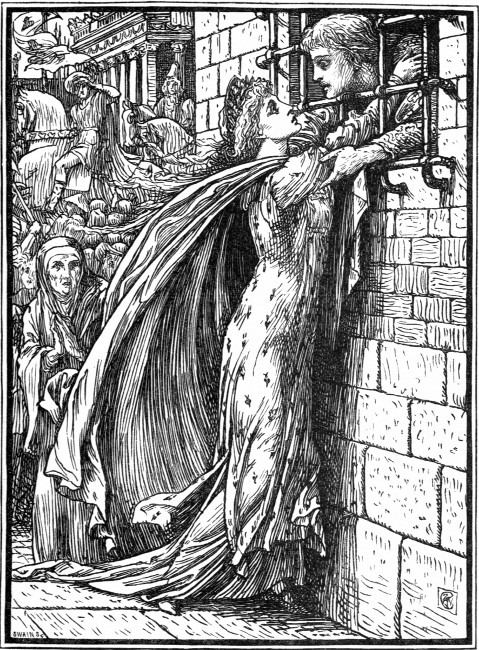

‘Then she kissed him softly thrice, and bid him adieu, and went out of the palace to her dear rose-tree in the garden. It was nothing now but a bare black stump. So Queen Blanchelys lay down on the ground, and put her arms round the trunk, and from the dead branch she tore a long smooth thorn, and pierced her heart with it, and the drops of blood trickled to the roots of the tree, and at once the serpent at the roots shrivelled and died, and the tree again began to bud and sprout.

When the King awoke in the morning the first thing he saw was the Queen’s letter, and he took it and read it at once, and as he read his cheeks turned pale, and he sighed bitterly, and then he called his courtiers, and told them what had happened, and they all went out into the garden to the rose-tree, under which lay dead poor Queen Blanchelys.

But the tree which before was only a piece of dead wood was covered with green leaves and rose-buds.

The King kissed the Queen’s pale face, and ordered that there should be a grand funeral, and that she should be buried under the rose-tree, and from that day forth the King thought of no-one but Queen Blanchelys … but Zaire was stripped of all her fine dresses and jewels … and was banished from the land, and had to beg her bread for door to door.

But when the rose-tree burst into bloom, the roses which were white before were as red as the blood which sprang from the Queen’s heart …’

— ‘Seeds of Love’, On A Pincushion & Other Fairy Tales (1877), Mary de Morgan

Exclusively for FolkloreThursday, the following is a story from Kate Forsyth, ‘Dreams of the Dead’, a secret chapter from her novel Beauty in Thorns.

Dreams of the Dead

St Pancras, London – November 1856

The first ghost that Mary de Morgan ever saw was her dead sister, Alice.

She was a cold breath on the back of Mary’s neck, a shiver like a goosey walking over a grave. Sometimes Mary felt sure she had seen her, a flash of something white in the corner of her eye.

Mary did not remember her sister. She had been only three when Alice had died. She did, however, remember her death. It had been dark and bleak and cold. Bare tree branches rattled against the window-panes. A fire had been lit in the drawing-room, and the air smelt fresh with the cent of the fir-tree that stood in its barrel in the corner. It had been decorated with gilded fir cones and bright bonbons and tiny red candles. Their flames danced in the icy draught from under the door.

Alice had been carried down from her bedroom and lay on a couch near the fire. She was very thin. Shadows in the hollows of her temples and cheeks, and between her knuckles. Her white nightgown hung loosely from the bones of her shoulders, showing the knobbles of her collarbones. Her mother had tucked her up in a warm blanket, but Alice was hot and restless and kept putting the blanket aside with a weak hand, only for her mother to tuck her up again. The family was gathered around the fire, the boys dressed in their best suits with frilled white collars, the girls in stiff frocks over pantalettes. It was the night before Christmas Eve. The older children were torn between excitement at the coming celebration, and solemnity at the sight of Alice, who had been absent from their games and arguments for well over a month. All they had known of her was the constant hollow cough that sounded through the house all day and night.

Alice had had an attack of the measles in early November, and afterwards her cough only got worse. Then the fever had come. The chills. The sweats. The blood-stained handkerchiefs. The abrupt wasting away of her flesh. Acute phthisis, the doctor called it. The maids called it galloping consumption. Mary had imagined a big black horse, racing away with Alice clinging to her back. She thought sometimes she heard the heavy hooves in the middle of the night, and felt them striking her in the chest.

Fire and darkness wrestled through the room. Mary remembered the gleam of golden light on her shiny black shoes, and the glimpse of snow-shaken black branches in the shadowy mirror. Mrs de Morgan gave them all hot mulled apple cider to drink, and William – who was fifteen – cracked walnuts for them all, while their father read them The Christmas Carol. Alice’s breathing had been harsh and labored. Her mother lifted her up so she could have a sip of the cider. It seemed to help. As her father read on, Alice’s breathing eased.

As Professor de Morgan read, the room grew silent. Even the crackling of the flames seemed to lessen. The wind outside hushed. The tree-branches ceased rattling, their branches weighted now with white. He reached the final page, and read, ‘God bless us, everyone!’ He shut the book, smiling.

Mrs de Morgan bent to kiss her daughter’s brow. There was a moment, just a moment, when everyone was warm and content and at ease, the story glowing through them. Then Mrs de Morgan began to scream. It was that moment Mary remembered. The piercing sound of her mother’s scream. The darkness rushing closer.

Things had been different after Alice died. Their father did not play bear with them anymore, or whistle merry tunes. Their mother dressed in black, and spent most of her evenings in a shadowed room, listening to the spirits rap. It was Alice she was listening for, and so Mary began to listen for her too.

Alice’s ghost came most often in the winter months, in the time around her death. Someone would hear footsteps where no-one trod, or the harsh rattle of breath in an invisible throat. Once Mary saw a girl dressed in a white nightgown standing out in the midwinter dusk, in the shadows under a tree. Yet when Mrs de Morgan ran out, heedless of the cold, there was no-one there. Just two faint impressions in the snow that might have been made by ghostly feet.

Sophia de Morgan had always believed that spirits could reach out from the Hereafter. When she was only ten, William Blake had been pointed out to her as a man who saw ghosts and angels. Her father told her that Blake believed God had looked through his nursery window when he was only four, and spoken to him. Blake had screamed, but ever since had seen all kinds of strange visions. Sophia had been fascinated by Blake’s story, and had badly wanted to see such things herself. When her neighbor was dying, she begged him to visit her and tell her about What Lay Beyond. The night of his death, she had been roused from sleep by strange knockings and breathings. Her white curtain had floated high and fluttered, although there had been no wind. She felt a presence hovering beside her. Sophia had not been afraid. Her neighbor had been a kind old man, and she could not think why his ghost would wish to hurt her.

Even before Alice got sick and died, Mary’s mother had liked to go to séances. She had first attended one by the famous Mrs Hayden. Mary had often heard her mother tell the story. They had sat in a circle in a poorly lit room, hands flat on the table, for a very long time. Slowly the table began to hum. Soft pattings were heard, like hands groping through darkness. ‘They are coming,’ the medium had said in a voice of rising excitement. Then the spirit had refused to rap for anyone but Mrs de Morgan. It had been the ghost of her sister Harriet, who told her, by rapping out the letters: ‘I am happy here with our mother and father.’ The ghosts of Mrs de Morgan’s family had often visited her after that, bringing her great comfort.

In the winter of Mary’s sixth year, her sister’s spirit visited her in a dream. Mary had followed a dove through a dark archway. Her sister had been waiting for her in the curve of another arch carved with gold. Alice had shown her four balls, two dark and two bright. In the dark balls, Mary had seen beasts. One had been trying to claw its way out of darkness up a steep precipice; the other had been trying to escape the light. In the first of the bright balls, a girl had been standing at the foot of the precipice, staring upwards. In the second bright vision, the girl had been dancing in the light at the top of the cliff with other children.

In the morning, Mary told her mother about her dream. Mrs de Morgan was sure it was a message from Alice, telling her she was safe in heaven. She questioned Mary again and again about all she had seen.

‘Are you sure it was Alice?’ she begged.

Mary nodded her head, putting her thumb in her mouth. She knew what her sister had looked like. Her mother had two photographs of Alice that she treasured. One showed a little girl, dressed in white with a black velvet hat, her hand entwined with her mother’s. Her brown hair hung loose, and her eyes looked as pale and uncanny a blue as Mary’s own.

The other showed her as a blur of white, hovering behind her mother’s shoulder in a photograph. Mary’s mother was convinced the white streak was her beloved daughter’s ghost, though Mary’s father thought it was some kind of double exposure. Mrs de Morgan would not agree. That photograph was even more precious to her that the photograph of Alice alive.

Mrs de Morgan had asked Mary to draw what she had seen, and Mary had done her best. After that, Mary had to tell her mother her dreams every single morning. On the days when she could not remember her dreams, her mother was sad and wan. On the days when Mary had dreamt of Alice, her mother was joyous and warm. So Mary did her best to remember. Sometimes, she made a dream up.

She did not think it would do any harm.

Win a copy of Vasilisa the Wise and Tales of Other Brave Young Women by Kate Forsyth (Adapter), & Lorena Carrington (Illustrator)

The wonderful folks over at Serenity Press have offered a copy of this brilliant new book for one lucky #FolkloreThursday reader this month!

Vasilisa who must try to outwit the fearsome witch Baba-Yaga.

Katie Crackernuts who sets out to save her sister from dark magic.

Flora, the gardener’s daughter, who marries a giant serpent to save a prince.

Fairer-Than-A-Fairy, a princess who is kidnapped by an evil one-eyed enchantress.

Lullala, in love with a prince cursed to be a lion by day and a man by night.

Rosemary, a Scottish lass whose baby is stolen by the wicked faery folk of the Sidhe.

Ursula, a princess replaced by a walking, talking automaton.

These are not your usual passive princess, waiting forlornly for their prince to come …Sign up for the #FolkloreThursday newsletter to enter (valid June 2018; UK & ROI only).

The book can be purchased here.

Recommended books from #FolkloreThursday